In 1914, Ralph Kerwineo, a self-assigned man from Milwaukee, had a dalliance with a woman who was not his wife, prompting his actual wife to report to the authorities that her husband wasn’t biologically a man at all. Kerwineo was arrested for disorderly conduct, but later freed. He was told by the judge he ought to dress as a woman while in Milwaukee if he wanted to stay out of trouble.

The case of Kerwineo, born Cora Anderson, captured the nation’s attention, but in her new book, True Sex: Trans Men at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, historian and Texas Tech professor Emily Skidmore identifies a surprisingly wide range of responses Americans had to the scandal. As Skidmore says in describing the case to the hosts of the Backstory history podcast, the national response was “automatically Ralph Kerwineo is a deviant, is someone who is pathological, and how terrible he took advantage of this poor woman.” (He was referred to as the “girl-man” in some articles.) “But what’s fascinating,” Skidmore continues, “is that what the Milwaukee papers really do is they interview Ralph Kerwineo’s former bosses and they’re trying to understand what his life as a man was like. And if his life as a man was respectable, then his foray into masculinity was understood as something that was, you know, kind of OK.”

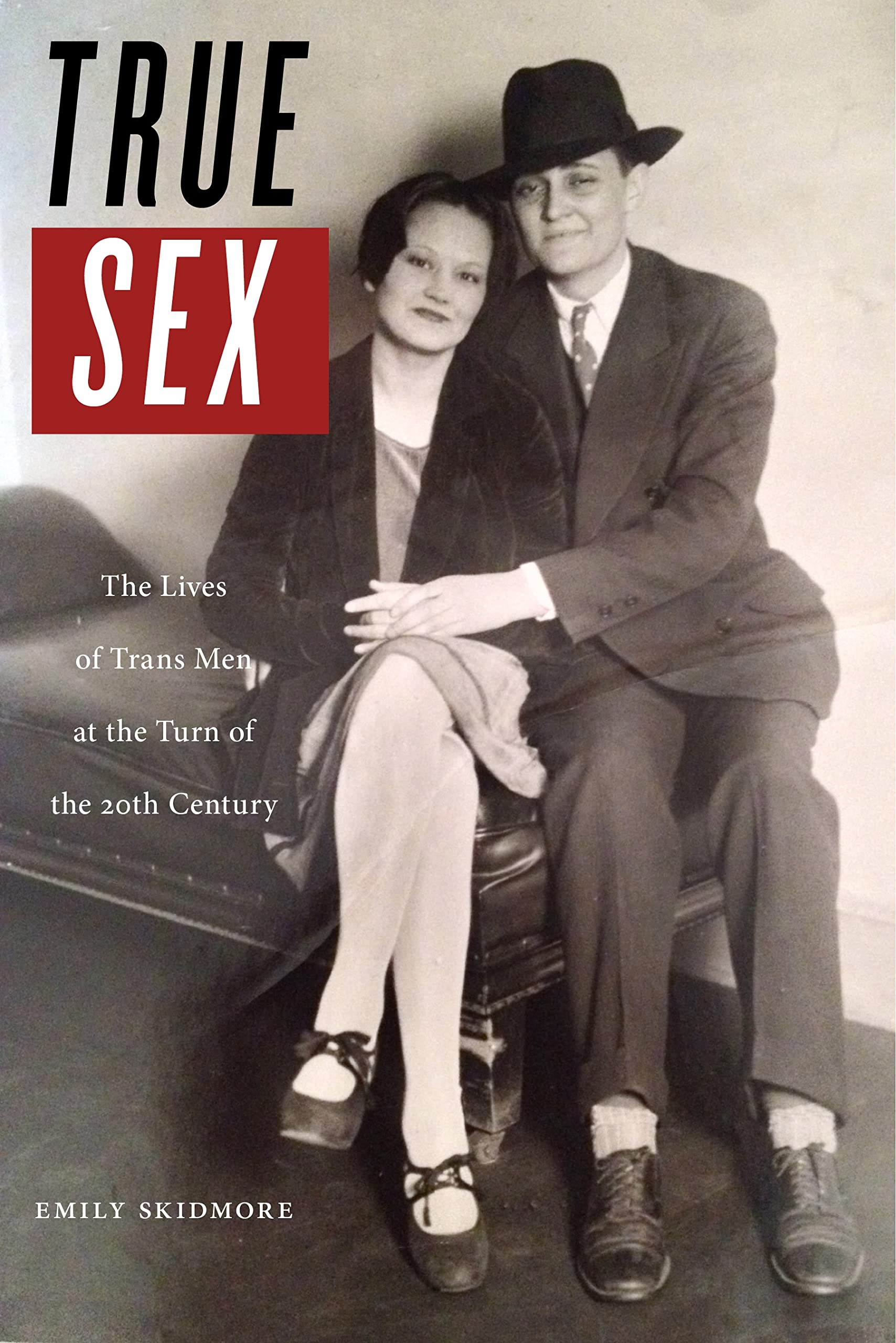

To listen to today’s politicians—prudish and prurient alike—one might think that gender categories were once perfectly stable and that transgender individuals are somehow an invention of the late modern age. But history shows that as a social category, gender has always been constructed, subject to debate, and to one degree or another, fluid. In True Sex, Skidmore explores the varied histories of American trans men long before that designation even existed. Reviewing newspapers and the literature of the field then known as “sexology,” as well as census data, court records, and trial transcripts, Skidmore weaves a tale of American gender that’s far more complex than many might think, one that reveals that it has never been a fixed reality.

In the absence of a framework for thinking about transgender experience, various terms were used to describe outed trans men, from “female husbands” at the end of the 19th century to the more scientific (and pathologized) “female sexual invert.” Eventually, these individuals were classified simply as lesbians. Of course, lesbianism would become the banner under which civil rights were initially won. Still, with each label came a further foreclosure of certain possibilities. Trans men were less able to pass as men and claim some of the privileges of “straight” life.