In 1858, Abraham Lincoln launched his campaign for the Senate seat from Illinois with his now famous “A House Divided” speech. While he did not predict disunion or civil war, Lincoln alluded to the country’s deep political divisions over slavery and concluded, “I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other.”

Even before what historians call the political crisis of the 1850s, the rise of an interracial abolition movement had encountered mob violence in the streets and gag rules in Congress. From then on, abolitionism in the United States was tied to civil liberties and the fate of American democracy itself. By the eve of the war, in 1861, most people in the northern free states felt that the democratic institutions of the country were being subverted.

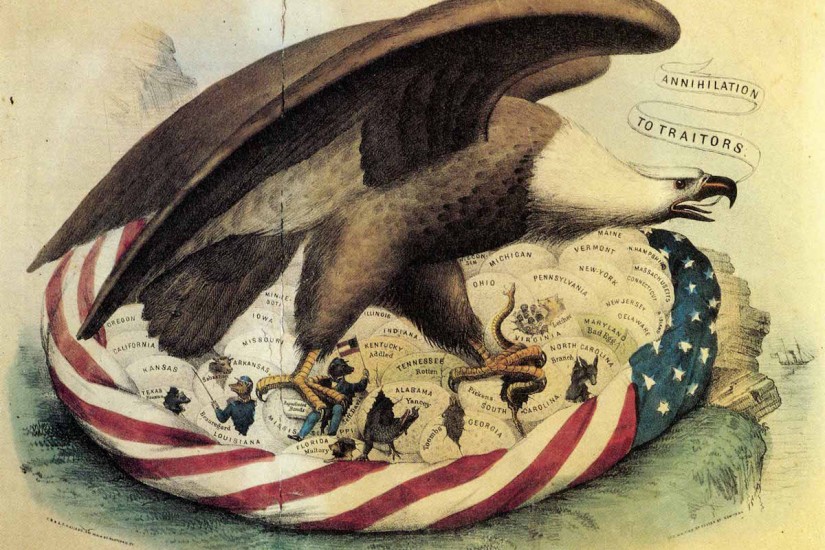

There are many Americans who feel the same way today. Some have pointed to the glaring, and growing, partisan divide in the US to conjure doomsday scenarios, including “civil war.” How does our own epoch of fierce political polarization compare to the decade that was rent over the issue of slavery before the Civil War? Predictions are often overwrought and historical analogies can be misleading, but the controversies that bedeviled that age and its legacies still haunt us. In certain ways, they foreshadow—or, perhaps, still condition—our own divided house.