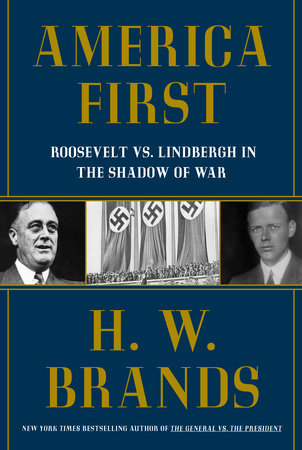

INDEED, IT IS BECAUSE OF THE RISE of a figure like Trump—and the simultaneous return of revanchist European imperialism, thanks to Putin—that Americans have rediscovered the story of Lindbergh in recent years. Celebrated around the world for his feats of aviation, Lindbergh launched a second career as the locus of pro-Hitler appeasement, doing everything in his power to prevent the United States from entering, let alone winning, the Second World War. It is a story well-trod in books like Susan Dunn’s 1940, Lynne Olson’s Those Angry Days, and Paul M. Sparrow’s recent Awakening the Spirit of America. And it’s one that Brands, as a historian and author on everything from the Revolutionary War to Ronald Reagan, similarly charts, tracing Lindbergh’s descent from simple celebrity to outspoken antisemite.

In approaching Lindbergh, Brands allows the aviator’s voice to take up entire paragraphs, and even entire chapters, of America First. Much of the book’s treatment of Lindbergh relies less on Brands’s analysis than on lengthy stretches of unbroken entries from Lindbergh’s journal, or on overlooked radio appearances and public talks he gave. In so doing—in allowing Lindbergh’s words to sit, untreated, on the page, for the modern reader to sift through—Brands brings Lindbergh to life in a way other historians haven’t managed to do.

And the Lindbergh who emerges is as myopic and nativist as popularly remembered. Describing Hitler’s war in Europe as “one half of the white race against the other half,” Lindbergh’s core belief is impossible to miss: that the United States must not seek to defeat Germany, whatever the cost. The Nazi regime, as Lindbergh sees it, did not threaten American interests. If anything, Lindbergh said, “the welfare of our Western civilization necessitated a strong Germany as a buffer to Asia”—and that he “would a hundred times rather see my country ally herself with England or even with Germany, with all her faults,” than with the Communist regime in Moscow.

But it wasn’t just that the United States should avoid war with the Nazis—it was that, as Lindbergh saw it, Hitler had done nothing wrong. In Lindbergh’s eyes, the fault of the Second World War lay not with Hitler’s genocidal mania but with countries like Britain and France, which declared war on Berlin for specious, spurious reasons—and which should not be allowed to win. “I feel it would be better for us, and for every nation in Europe, to have this war end without a conclusive victory,” Lindbergh said at one point. “I think a negotiated peace would be to the best interests of [the United States].”