Confronting the Mistakes of the Past

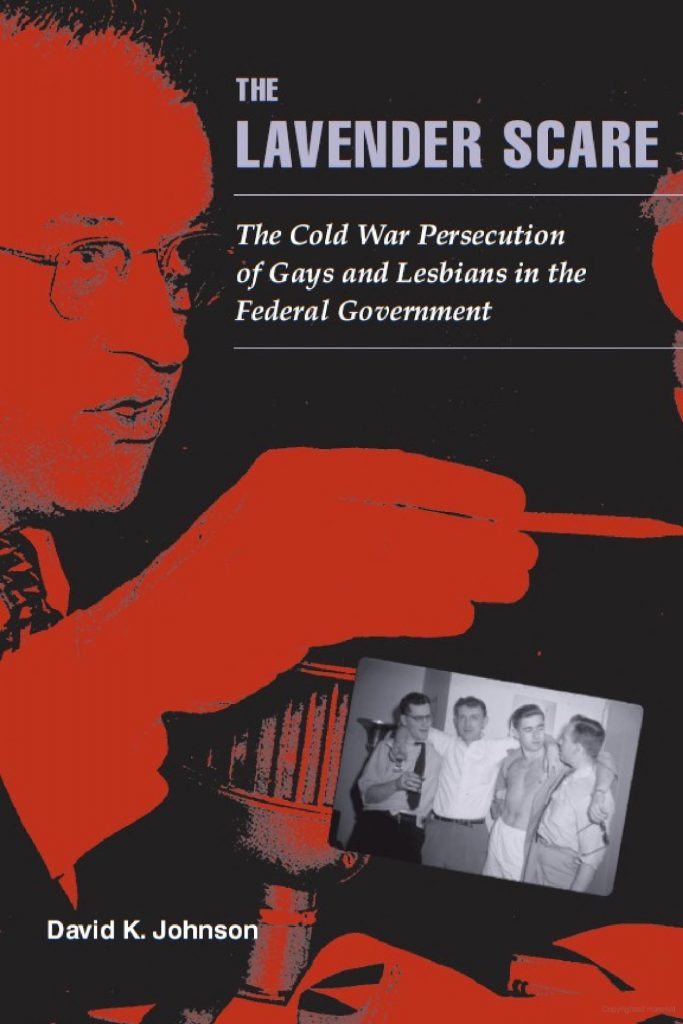

It took half a century for the history of the Lavender Scare to become widely known and even longer for the State Department to begin exorcising its demons. External pressure from concerned federal legislators has played a key role in encouraging the Department to act. So too has the work of historians like David Johnson, the author of a landmark 2006 book entitled The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government. Citing Johnson’s book, Senator Ben Cardin (D-MD) asked then-Secretary of State John Kerry to issue a formal public apology on behalf of his department in November 2016. Two months later, Kerry obliged, releasing a written statement that constituted the first official acknowledgment of the federal government’s complicity in the Lavender Scare. “The Department of State,” the statement explained, “was among many public and private employers that discriminated against employees and job applicants on the basis of perceived sexual orientation” during the Cold War. “These actions were wrong then, just as they would be wrong today.” At a Pride Month event last summer, Assistant Secretary of State Wendy Sherman went further, noting with regret that her predecessors had been “especially aggressive” in their persecution of LGBTQI+ personnel. As Sherman spoke, a Pride flag, raised in honor of the Lavender Scare’s victims, fluttered above the State Department’s headquarters in Foggy Bottom for the first time in its history.

It is tempting to interpret all these apologetic statements and the commemorative ceremonies as reassuring proof that the American foreign policymaking establishment, having finally owned up to its mistakes, is now marching inexorably towards a kinder, gentler future. But treating the past like a measuring post for progress isn’t likely to teach us very much about the root causes of the problems we want to solve, nor is it likely to help us solve them. A much more comprehensive reckoning with the State Department’s shameful history is in order.

Administrative history is useful insofar as it forces us to confront an uncomfortable reality: institutions, especially old ones, have a way of defying the best intentions of their own leaders. Bad administrative outcomes aren’t necessarily born of malice. Sometimes, they’re the products of seemingly innocuous routines, invented long ago to perform tasks we would now deem absurd or unsavory. It is up to us to assign our institutions new and better tasks, and if we want to see those tasks accomplished, we must be prepared to ruthlessly interrogate the underlying assumptions that determine institutional behavior.