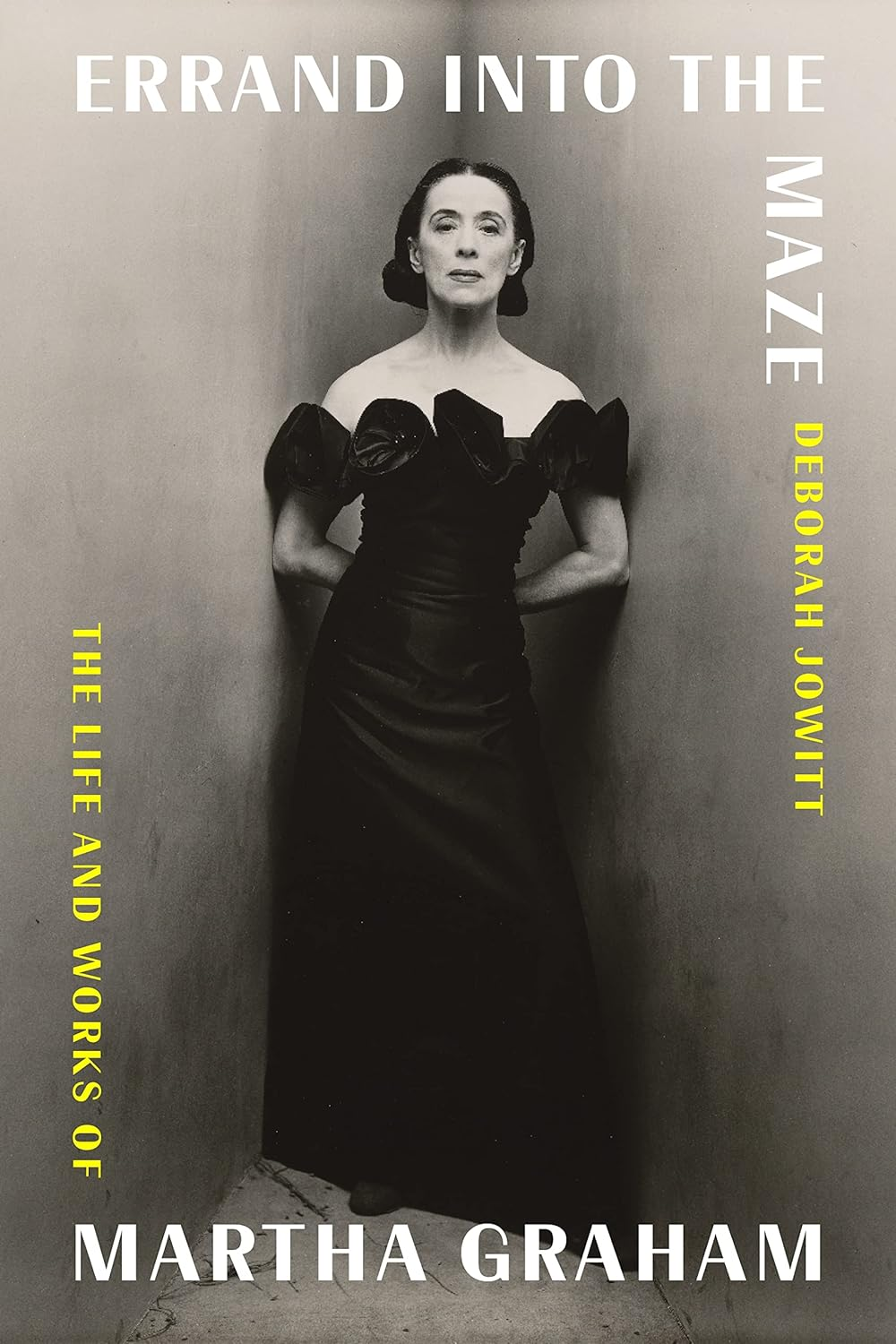

Martha had an uncanny knack for finding the right collaborator. She worked with Aaron Copland on Appalachian Spring (1944), for which the composer earned a Pulitzer Prize for his score. It became Martha’s most celebrated dance piece. Appalachian Spring is a much grimmer version of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town; Martha’s personae are members of a primitive Pennsylvania community who spend their lives in seclusion, staring at a wilderness that cannot be witnessed from the stage. Even darker was Errand into the Maze (1947), in which a monster in a mask chases the protagonist—Martha—through a labyrinth that might very well be the turbulence of creativity. The title comes from “Dance Piece,” a poem by Ben Belitt:

The errand into the maze,

Emblem, the heel’s blow upon space,

Speak of the need and order the dancer’s will.

But the dance is still.

Martha was drawn to the myths of wild, strong-willed women, such as Medea, Phaedra, and Clytemnestra, and she composed dance pieces about them. But she turned to alcohol for consolation as her career declined. She had three facelifts, completely destroying her “skeletal glory.” She stopped composing, then composed again. Famous for her batwing sleeves and wide skirts in her dance routines, Martha became a spectral creature. She required nurses day and night, trapped as she was in a body that had betrayed her. She died of pneumonia in April 1991, a month before her 97th birthday.

Jowitt has written a powerful testimony to Martha Graham and modern dance. Martha understood that movement was melody. Her insistence that she was creating art rather than a diversion often bewildered audiences, who wanted to be entertained and couldn’t make the imaginative leap into her landscapes. She and her company of women and men leapt about at precipitous angles, creating an aura of vertigo, with “staccato runs, sudden stops, abrupt kicks.”

“Ugliness,” she said, “may be actually beautiful, if it cries out with the voice of power.” This is what we find in The Witch of Endor (1965). Martha portrays the witch, who after encountering King Saul, plunges the audience into a world of dance never seen before. At least in Martha’s notes, the witch—“pushes Saul / rides Saul / stands on Saul.”