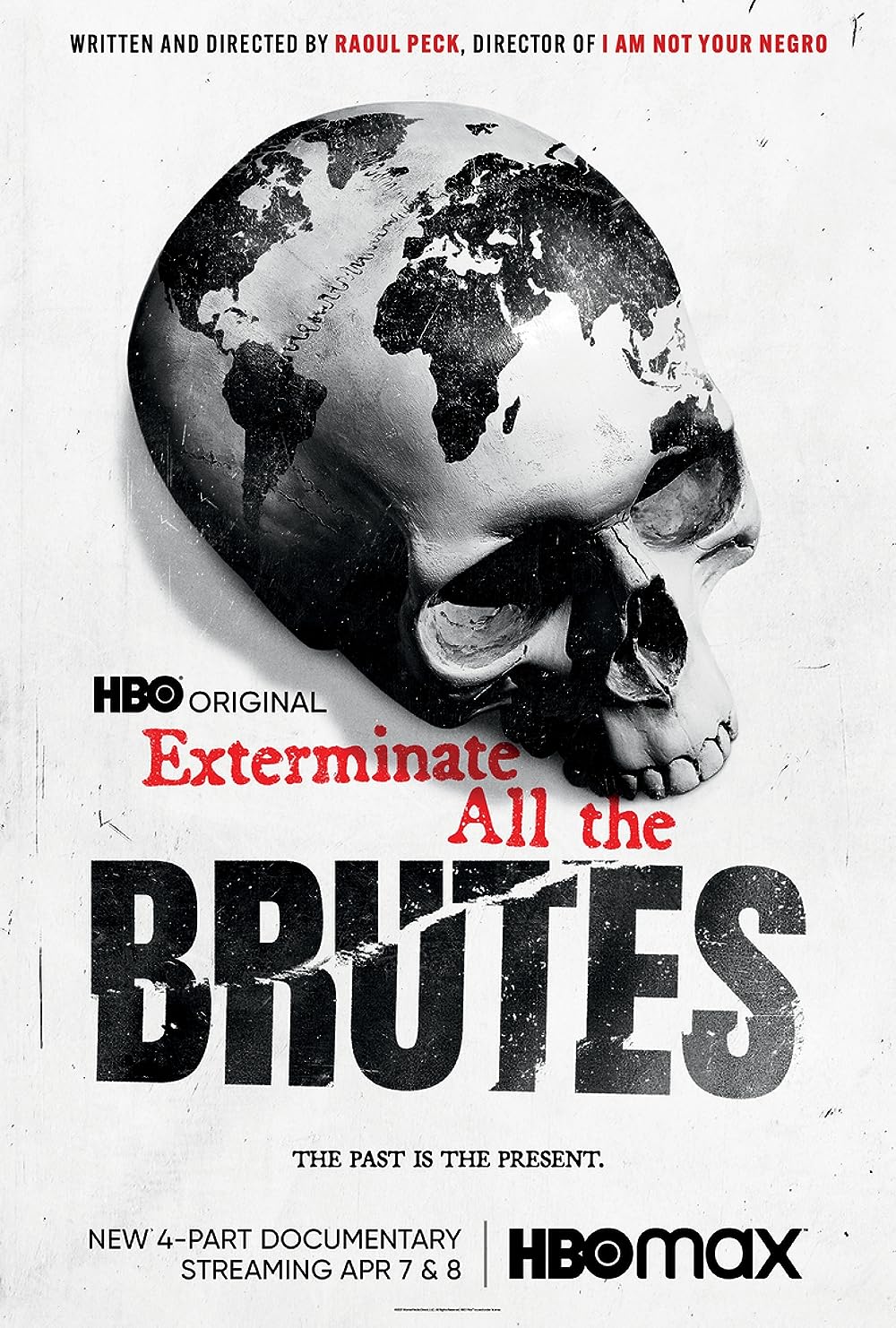

Exterminate All the Brutes, which draws heavily from Sven Lindqvist’s book of the same name, is grandiose in scale and unrelenting in detail. Much of the series is set in and around 1492, but Peck also weaves in the era of his upbringing. Marshaling a dazzling array of recreations, archival footage, and family photos, Peck issues a clear, contemporary political message: to understand the America of today we must face the original extermination that made it possible.

“The very existence of this film is a miracle,” Peck says during the narration of the series’s final episode — a statement echoed by nearly every American critic who wrote about Exterminate. “How Peck tells the story of white supremacy,” The New Yorker’s Richard Brody wrote, “matters less than the fact that, at last, it is indeed being comprehensively, insightfully, compendiously told.” Daniel D’Addario likewise paused in his Variety review “to give HBO credit” for airing Exterminate at all — a sentiment shared by Jon Schwarz in The Intercept. “Before this moment in history, it would have been impossible to imagine that one of the world’s largest corporations — AT&T, owner of HBO, with a current market cap of $220 billion — would have funded and broadcast a film like this,” Schwarz wrote. “The fact that it somehow squeezed through the cracks and onto our TVs and laptop screens demonstrates that something profound about the world is changing.”

I’m generally skeptical when I see art lauded for its liberal bona fides (diversity, representation, etc.) — these are grounds for praise that tell us more about the limitations of a white audience than about a work itself. But even for a wary Indigenous viewer like me, it was tempting to come away from Exterminate believing that American society is working, in some way, toward understanding, owning, and teaching its true history. For a brief moment, I was lulled into believing what both Peck and the critics said, that the existence of a radical work on HBO must be a marker of progress — if not for all of the U.S., then at least for its entertainment industry.

But the further away I got from my first encounter with the film, the less I found revelatory about Peck’s thesis and the bloated project around it — and the less I felt comforted by the cooing critics. Exterminate debuted on a streaming service that costs at least $100 per year to access; anyone who clicked knew, to a degree, what they were signing up for — they likely already agreed with Peck’s general arguments, even if they lacked the gory specifics.

While Peck and so many others have been chipping away at the foundational myths of America, conservative reactionaries have only tightened their stranglehold on state legislatures and school curriculum standards around the country, seeking to further entrench the very myths that Peck and others aim to dismantle. By situating his project within these kinds of historical debates, Peck made it a bit too easy for the white HBO viewer — so focused on acknowledging the sins of the past — to forget that the descendents of the tribes they’re watching be decimated are still here, and that their oppression is ongoing. The problem with constantly fighting over historical accounts is that doing so keeps us distracted from the battles that are still being fought — those over political and legal issues, land and water rights, and other matters of sovereignty that determine the lives and futures of our communities. Decolonizing the narrative doesn’t, in itself, decolonize the state.