Ryan, who had severe hemophilia A, frequently used Factor VIII — a blood-clotting agent created with plasma pooled from thousands of donors and used to treat hemophiliacs’ bleeding episodes. The specialists at Riley suspected that Ryan had acquired pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) through contaminated Factor VIII. At the time, a PCP or Kaposi’s sarcoma diagnosis served as a de facto AIDS diagnosis, since such opportunistic infections were incredibly rare before the “discovery” and spread of AIDS in the early 1980s. When a biopsy determined that Ryan had, in fact, contracted PCP, it essentially confirmed that he had AIDS.

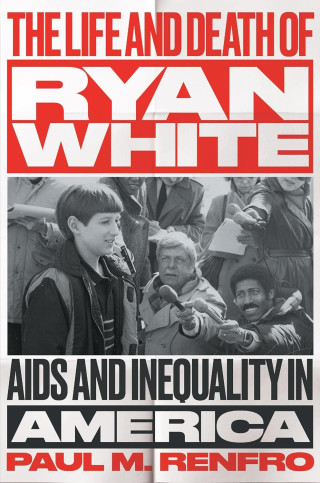

Little did Ryan, Jeanne, or anybody else know that Ryan would become the most famous person living with AIDS in the United States, if not the world, until his death from AIDS-related causes in April 1990. Paradoxically, Ryan’s fame could be attributed both to his seeming normality and his status as an exceptional “victim.” As Jeanne put it in February 1986, Ryan helped “show the world another side of AIDS.” When he passed away at the age of 18, NBC Nightly News called him “the young man who taught the world that not all AIDS victims are gay, abuse drugs, or live in big cities.”

For all that Ryan did to challenge harmful and overly simplistic conceptions of AIDS, his story — especially as it was presented at the time in the national press — also reinforced existing notions of “guilt” and “innocence.” Because White had fallen ill “through no fault of his own” — as many put it — those familiar with his story could easily blame gay men and other historically subjugated groups for Ryan’s plight, while ignoring the broader institutional and societal failures that had sparked the AIDS crisis in the first place.

And now, similar patterns of blame and absolution have emerged during the pandemic in the U.S. People of Asian ancestry have been maligned and abused for supposedly spreading COVID-19, while some essential workers have been venerated for potentially exposing themselves to the virus in the name of preserving consumer capitalism. Furthermore, uneven access to vaccines and health care in the U.S. and globally has widened existing gaps in vulnerability (as demonstrated by the rise of the Omicron variant) and exacerbated the stigmas surrounding specific populations — especially poor and working-class individuals, undocumented people, and those alienated from the medical establishment.