Godine, a scholar and lecturer based in Saratoga Springs, has been writing social histories of New York’s North Country for more than three decades. In The Black Woods she recounts the White abolitionist Gerrit Smith’s plan, hatched in 1846, to offer 120,000 acres of undeveloped Adirondack land to some three thousand Black New Yorkers. In Smith’s vision, these parcels of land, valued at $250 or more, would allow Black men to meet the state’s property requirements for voting, imposed in 1821.

Smith’s gifts did not come ready-made. The plots had to be cleared and improved, daunting tasks for families otherwise unable to meet the property qualification. Perhaps two hundred intrepid Black settlers moved north from different parts of New York state and the South. They established farms in the three counties at the far northeastern corner of the state—Essex, Franklin, and Clinton—that endured into the late nineteenth century.

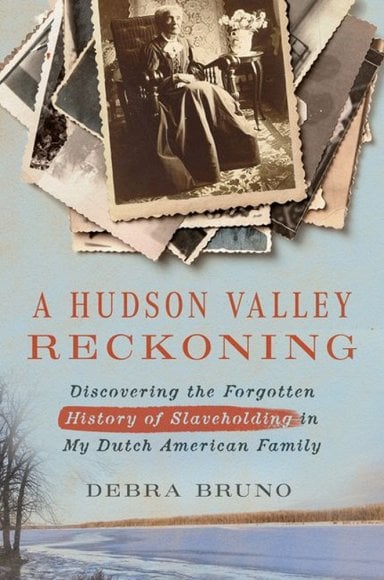

Bruno, a journalist originally from the Hudson Valley, now lives in Washington, D.C. Her father’s family were Italian immigrants; growing up in Athens, near Coxsackie, in the 1960s and 1970s, she thought of herself as Italian American and was only vaguely aware of her mother’s deep Hudson Valley Dutch heritage. Ignorant of the region’s social and political history, she took its Whiteness for granted and did not think to question the commonplace that slavery and Black people belonged to the South. But late in the 2010s, her genealogical research on Ancestry.com revealed more than a quaint, bucolic saga of wholesome farmers.

It took Bruno about a decade to discover the history of slavery in Ulster and Greene Counties: exit 18, New Paltz; exit 19, Kingston; exit 21, Catskill; exit 21B, Coxsackie. Through a Facebook group called I’ve Traced My Enslaved Ancestors and Their Owners, she connected with Eleanor Mire of Malden, Massachusetts, a descendant of the people Bruno’s ancestors had enslaved.

Bruno and Mire learned that their seventeenth-century ancestors were part of an economy largely based on barter. Purchases, loans, and collateral were accounted for in measures of meat, wheat, oats, peas, tobacco, and human beings. People held as chattel represented a substantial part of the region’s population and wealth. The 1796 last will and testament of Bruno’s five-times-great-grandfather Isaac Collier bequeathed to family heirs “one other Feather Bed, one Negro Boy named Will and my sorrel mare and sorrel stallion, one waggon & harrow,” and “my negro wench named marie.” Bruno was devastated to find this. “They all owned slaves,” she writes. “And they too were all my kin.”