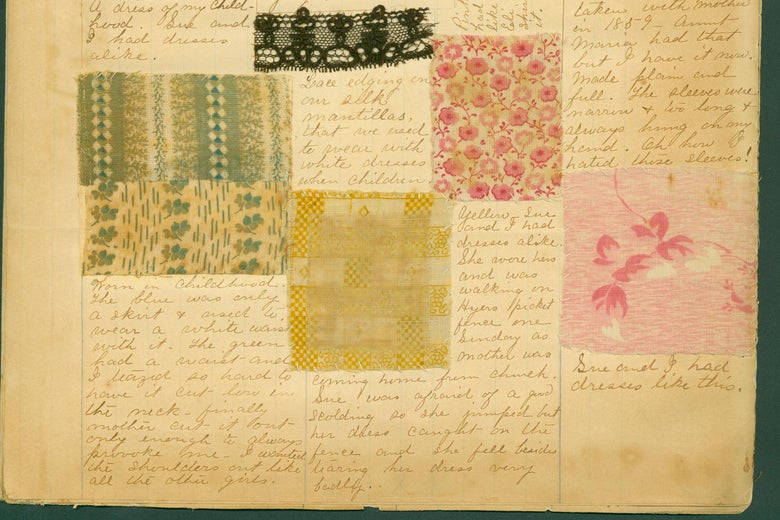

Hannah Ditzler Alspaugh started work on this detailed fabric scrapbook in 1887, and ended it in 1903, with a bit of silk from her wedding dress. Alspaugh annotated each sample with details about a garment’s making, remaking, circumstances of use, and eventual demise; some of the samples date back to the Civil War. The book, created by a woman who had a beautiful mania for documentation, is a singular artifact of the culture of 19th century domestic dress-making. It chronicles people’s relationship to clothing at a time when most who, like Alspaugh, weren’t super-wealthy had no choice but to sew their own.

“Hannah’s notes are extremely detailed and extremely emotional,” said Dina Kalman Spoerl, exhibits team leader at Naper Settlement in Naperville, Illinois, whose article in the American Historical Association’s Perspectives on History magazine introduced me to this document in her organization’s collection.* “Everything has a label on it. Everything has at least a line about when she got it, how she wore it, what she did with it, during the course of its life with her.”

Alspaugh, whose farmer father moved to Naperville from Pennsylvania, was a teacher, artist, and librarian. She remained unmarried for most of her life, before finally wedding a cousin in her middle age. Though other women of the time also created fabric scrapbooks, Alspaugh’s has much more detail than most; at 42 pages, it describes hundreds of samples.

Left-hand column, notation under two stacked samples of cream-colored fabric with blue and green patterns: “Worn in childhood. The blue was only a skirt and used to wear a white waist with it. The green had a waist and I tried so hard to have it cut low in the neck – finally mother cut it out only enough to always provoke me. I wanted the shoulders cut like all the other girls.”

Alspaugh’s mother’s presence runs through this book, showing how the creation of clothes before the wide availability of store-bought garments demanded work from all the women in a family. This particular memory destroys any sepia-toned vision of domestic industriousness and family togetherness the sentence before this one might evoke. Imagine making a garment for your begging teenage daughter, and fighting over necklines all the way!