They called themselves the Wide Awakes: one of America’s largest, weirdest and most consequential political organizations, now nearly forgotten. In Boston, many had escaped slavery. In St. Louis, many were radical German immigrants. In D.C., their rallies mixed Yankee federal clerks with sons of Southern families. In Connecticut, where they got started, they were working-class kids with shady political backstories. And in 1860, this diverse coalition of young Americans drew the line against slavery and help to elect Abraham Lincoln.

Their success can tell us a lot about cobbling together a coalition in a fractured, tribal, distrustful age.

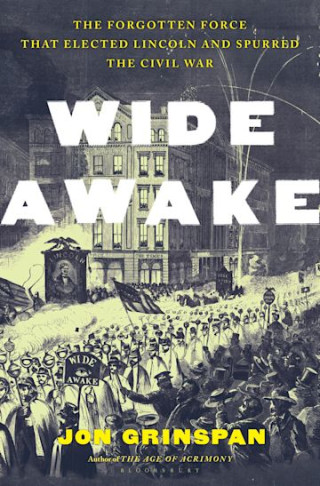

Clad in militaristic black capes, marching by torchlight through America’s cities, the Wide Awakes alarmed the Southern aristocracy of enslavers — which was exactly what they hoped to do. The movement drew its mammoth size and unnerving force from the resentment many Americans felt toward “Slave Power”: the wealthy planters who pushed to expand slavery and brutally suppressed opposition.

Started by a few kids barely old enough to vote in February 1860, the Wide Awakes were believed to be half a million strong by August of that year, with companies from Maine to California, Virginia to Kansas.

To understand how shocking this coalition was, we need to rethink the politics of antebellum America. Instead of a nation split between the absolutes of Slavery and Freedom, most Americans fell somewhere on a spectrum between the two. Just 2 percent of the population in 1860 actually enslaved anyone, and those Americans trapped in slavery made up another 12 percent of the nation’s men, women and children. That left 86 percent of Americans who were neither enslavers nor enslaved. Some enthusiastically supported slavery, while others prayed for the practice to end. But most — especially among the large northern majority — found slavery distasteful while also objecting to what they saw as the radicalism of Abolition.

Caught in the middle, this majority bounced from party to party, explaining much of the tumult of mid-19th-century politics. Enslavers skillfully exploited the unsettled situation and spent the 1850s demanding more slave states, the right to keep enslaved people even in free states, the prohibition of speech and writing against slavery, and a requirement that free states assist in hunting fugitives.