The first Japanese immigrants to intentionally sail to California stepped foot in San Francisco in 1869. They were led by John Henry Schnell, a Prussian man serving as a military adviser to a deposed Japanese ruler.

To understand why a group of samurai suddenly packed up and left Japan, it helps to have a quick primer in Japanese history. These families were fleeing: They’d seen the writing on the wall that their centurieslong reign as part of Japan’s ruling class was over. Since 1603, the Tokugawa Shogunate had ruled the nation as a military dictatorship. The Tokugawa rulers were strict isolationists, keeping foreigners out in order to maintain what they viewed as cultural purity. That all changed in 1853, when Commodore Matthew Perry and the U.S. Navy arrived to force Japan’s ports open to trade.

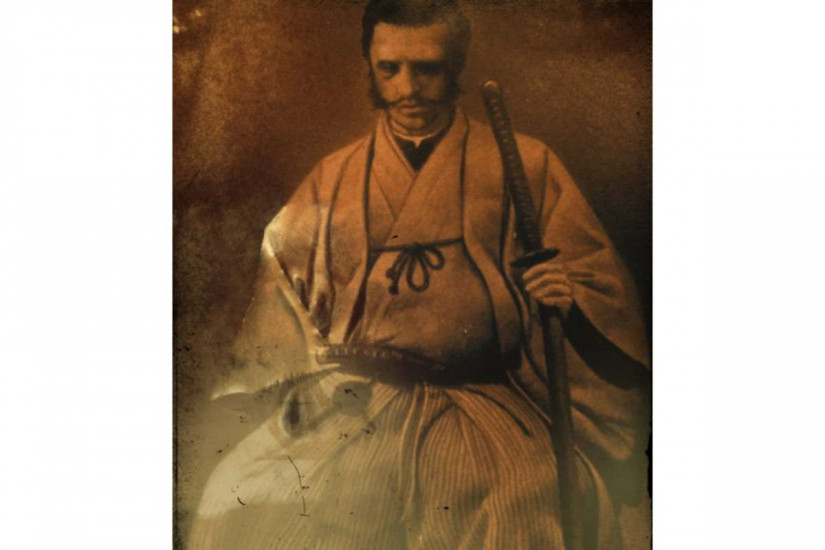

The metaphorical floodgates now open, Japanese society began to shift. Some yearned for more outside contact, and they aligned themselves with a faction hoping to overthrow the Tokugawa Shogunate and replace it with the Japanese royal family. In 1868, the Boshin Civil War began. That year, a force of thousands of samurai in the province of Wakamatsu were defeated by the emperor’s army. In the aftermath, Katamori Matsudaira, the regional leader of samurai, was captured. His samurai, and his Prussian friend Schnell, were left on the losing side of a war.

Schnell used $5,000 provided by Matsudaira to purchase a ranch near Gold Hill in El Dorado County. It was dubbed the Wakamatsu Silk and Tea Farm, although newspapers sometimes mistakenly called it “Wakamatz” farm.

The media coverage was breathlessly excited and inherently racist. "Unlike the Chinese, they are not exclusive, clannish or secretive in their habits,” the Sacramento Bee wrote. "Japanese conduct themselves with dignity,” added the Daily Alta California. “... They cannot safely be treated as Chinamen often are.”

Newspapers emphasized the social status of the immigrants, assuring white Californians these warriors were from the gentleman class of Japanese society. Although they worked for Schnell, they were "not serfs but free,” the Daily Alta clarified upon their arrival.

By summer, the colonists were busy cultivating Wakamatsu Farm. Each family was allotted tea plants and mulberry trees, the foundation of the flawless silk Japan is famous for. They planted bamboo (“It far surpasses our vegetables in nutriment and in kindly digestion,” the Alta California wrote, with all the “virtues of the artichoke and the asparagus.”), and created a small lake into which they released fish for food. In October, a reporter from the Bee took a tour of the farm. He noted the mulberry trees looked healthy and speculated California may never need to import tea again.

"There appears to be scarcely a shadow of a doubt of the complete success of the experiment,” he wrote — but then alluded to the fact not all was well on the Wakamatsu farm.