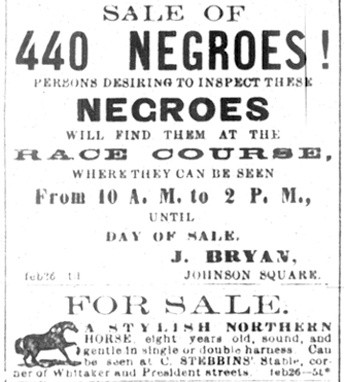

The notorious slave trader Joseph Bryan was enlisted to conduct the Butler slave auction and it was originally scheduled to take place in Savannah's Johnson Square, directly in the city's center, where Bryan's slave holding pens and brokerage was. But it was soon determined there wouldn't be enough room to accommodate the buyers they expected, so the location was moved to the Ten Broeck Race Course two-and-a-quarter miles west of downtown.

For weeks before the auction, Bryan took out ads in papers across the south advertising the sale. It became the talk of the town and speculators from as far as Louisiana and Virginia came to Savannah to ply their bids. One of the ads that ran in the weeks before the auction in the Savannah Daily Morning Newsread:

It was said that the hotels and bars were all full to capacity in the days leading up to the auction and the city was abuzz with discussion about the great sale. Among the crowd was an undercover journalist from the north, Mortimer Thomson, who wrote under the pseudonym Q. K. Philander Doesticks. Thomson had been sent to Savannah by the New York Tribune editor and noted reformer, Horace Greeley, to report on the sale.

Thomson posed as a potential buyer to get close to the action and judging by the reaction in the South once his piece was published, it was a wise decision for him to travel incognito. After “Great Auction Sale of Slaves at Savannah, Georgia” came out in the Tribune, it was republished in Philadelphia and London and caused an international stir. Threats on his life from public officials in the South were issued. They claimed the piece was an anti-slavery hit-job by northern abolitionists. In fact that's exactly what it was.

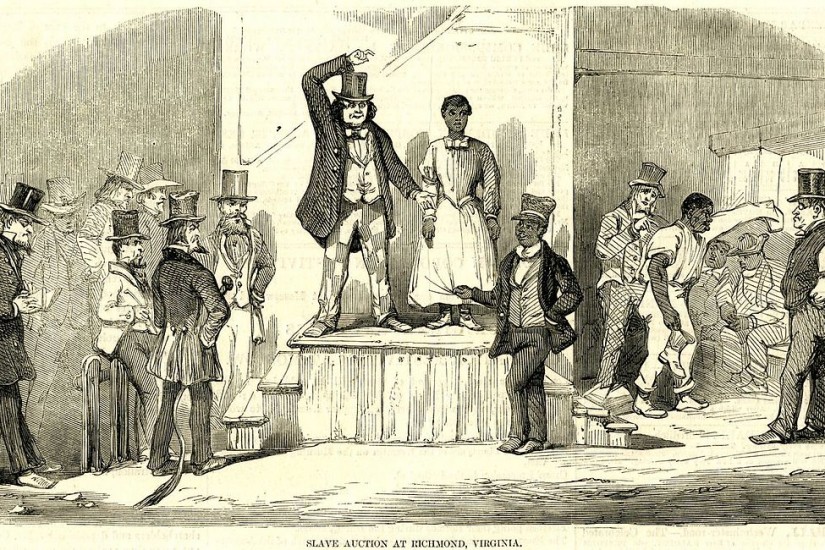

Thomson extensively recounted the events of the auction in damning detail for his article (years later reissued as a sequel to Kemble's journal). He explains how, upon arrival, the slaves were stuffed into the horse and carriage stalls at the race track. As he writes, “Into these sheds they were huddled pell-mell, without any more attention to their comfort than was necessary to prevent their becoming ill and unsalable... On the faces of all was an expression of heavy grief.” He goes on to note that some of the slaves appeared to have resigned themselves to the “hard stroke of fortune” that was their fate as human property, while others “sat brooking moodily over their sorrows, their chins resting on their hands, their eyes staring vacantly, and their bodies rocking to and fro, with a restless motion that was never stilled.”