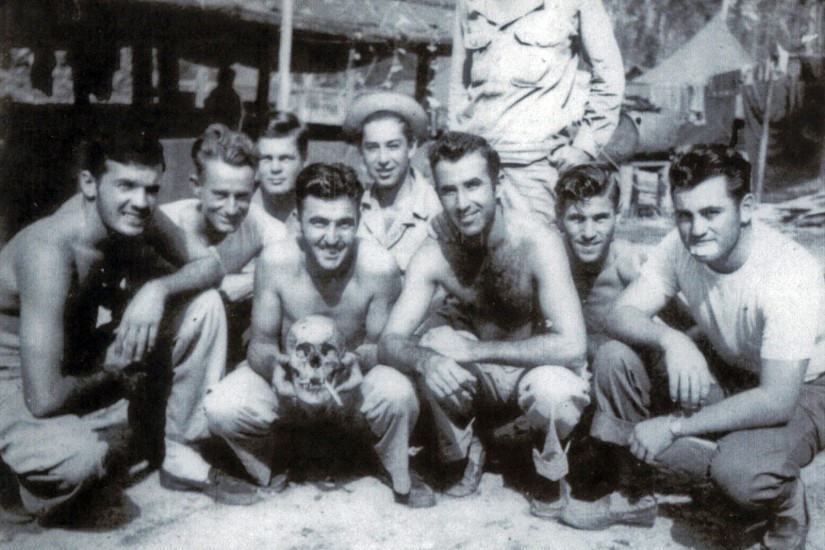

Several years ago, I was sifting through a box of American soldiers’ Brownie camera snapshots from the Korean War in a small private archive an hour outside of Kansas City. Among the thousands of expected everyday scenes—buddies, bases, camps, landscapes, drinking—are images of soldiers posing with human skulls.

In one series, a soldier has wrapped a blanket around his head and holds the skull out of the top, pretending to be a walking dead man, while his friend grabs the blanket and smiles for someone outside the frame. Another image finds the skull adorned with an infantry steel helmet, held at waist level by a soldier dangling a cigarette from his lips. A third soldier cradles the skull near his stomach, smiling uncertainly. The scenes take place in camp during relaxed downtime, with other soldiers walking unconcernedly in the background.

The practice of collecting enemy body parts, particularly skulls, as trophies, and repurposing them into objects of delight emerges often in the history of the United States. Trophy skulls and bones, fingers and skin, became objects of sentiment: they were carved into lamps and letter-openers, given pet names, or exchanged as love-gifts, while snapshots of trophies became nostalgic reminders of soldierly camaraderie.

Highly public and prized objects during wartime, shown in traveling shows and photographed for the pages of Life magazine, trophies were also officially condemned by military and government authorities and subsequent wartime histories. Trophy bones and photographs moved easily between state sanction and state condemnation, private affections and private mourning, public display and public unease. In the aftermath of war, trophies shifted into private circulation, as family mementos in attics, in shoeboxes of snapshots, and in the footnotes of war histories. Over decades, they continually reemerge, vexing testimonies of the fundamental violence of American power and of the cultural forgetting that is its shadow.

The history of American expansion can be traced through the severed body parts left in its wake. Skulls, teeth, severed genitalia, fingers, arm bones, and skin marked who had won and who had lost, whose bodies could be dismembered and who could draw entertainment and reassurance from their display.