Is there a way to look at Sly Stone—a musical genius and, for a couple of years, an avatar of spiritual freedom—that isn’t dualistic, split-brained, one thing in opposition to another? That isn’t about light versus darkness, up versus down, Logos versus Chaos, good drugs versus bad drugs, having it all versus losing it all, and on and on? “Without contraries is no progression,” William Blake said, but still—I find myself groping for another plane of understanding. I want to see him as the angels do. We might need to evolve a little bit to get a handle on this man.

To the binary American eye, certainly, he soared and then he smashed. Sly Stone held the ’60s in the palm of his hand. He had the plumage and vibration of Jimi Hendrix and the melodic instinct of Paul McCartney. His music married ballooning hippie consciousness to the tautest and worldliest and most street-facing funk: Its end product, its neurochemical payload, was an amazing, paradoxically wised-up euphoria. A rapture petaled with knowingness, with slyness.

Live, he could bend time to his will like James Brown. His band Sly and the Family Stone—polyracial, polygendered, poly-freaking-phonic (you could never quite tell which voice was Sly’s, and he himself had several)—was a crucible of joy, a crucible of possibility, an experiment that took on the character of a proof: People could live together. America could work. Love and justice were real. For about a minute. “I can’t imagine my life without Sly Stone,” Cornel West says in the 2017 documentary On the Sly: In Search of the Family Stone. “Sly created a music that became a place where we could go to have a foretaste of that freedom, of that democratic experience. Even though we couldn’t live it on the ground.”

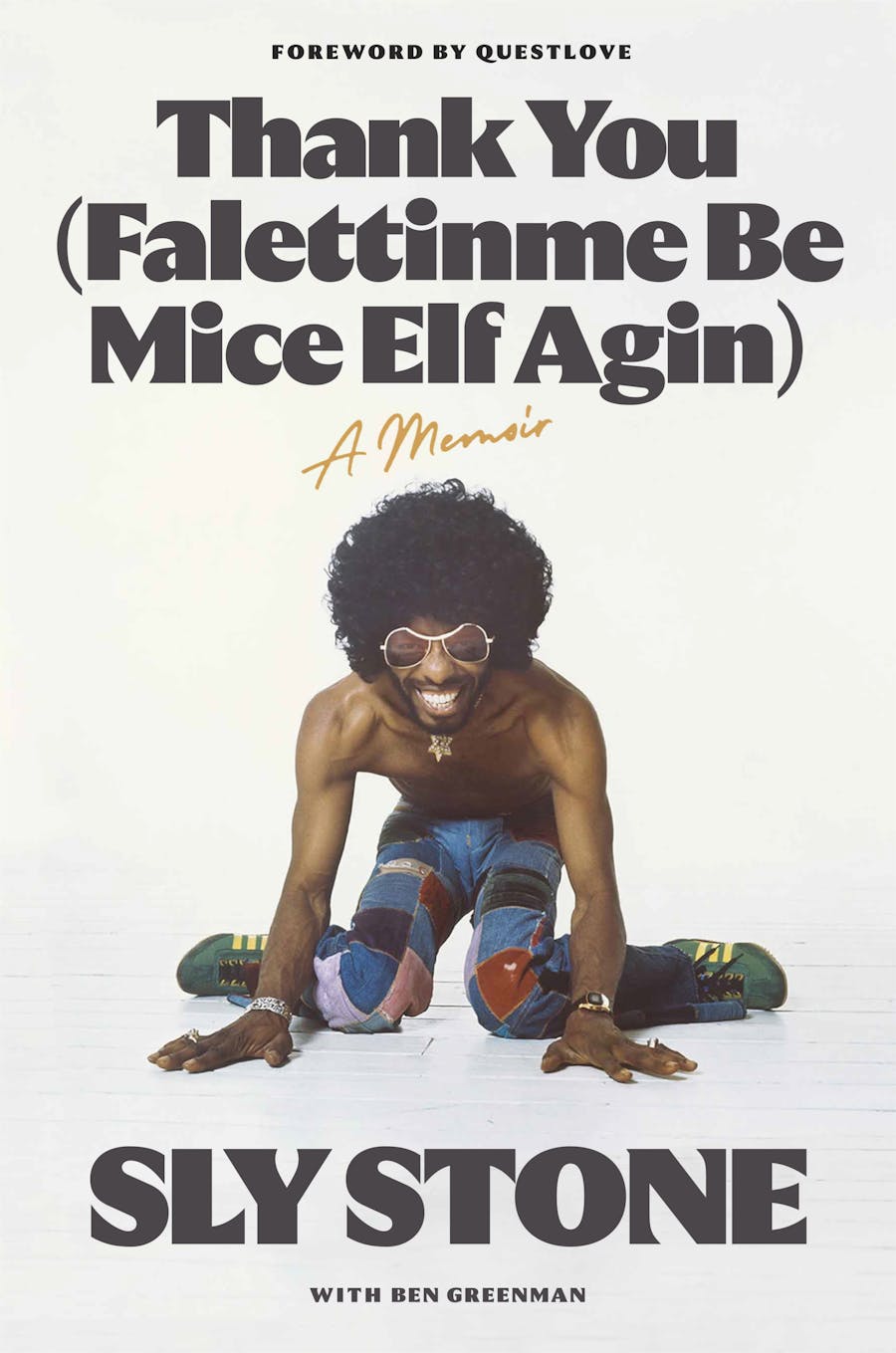

And by 1975 it was essentially over: his creativity squandered, his reputation in tatters, cocaine and PCP and paranoia everywhere. Decades of obscurity followed, punctuated by occasional failed resurrections. Plenty of people, upon hearing about his new memoir, Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin), written with Ben Greenman, will be surprised to learn that he is still alive.

But Sly lives. And the resourceful Greenman, whose publishing credits include the co-writing of a memoir by George Clinton, has coaxed, wheedled, massaged, used God knows what processes of titration and palpation to extract a fascinating book from him. “I have some questions, not too many,” he tells his subject in the moody snippet of transcribed conversation that prefaces Thank You. “We don’t have to do them all.” “We don’t have to do them at all,” answers Sly.