Reading Tamson Pietsch’s scholarly, consistently entertaining book, it is sometimes hard to identify anything that went right. The tour, which ran from September 1926 to May 1927, was disowned by its initial sponsor, New York University, who also dismissed the figure behind it, Professor James E Lough. It was not just that his Floating University inspired such dreadful coverage. It was not just that the failure to enrol enough male students required him to take on board other paying passengers, including a number of women whose relationships with the men provoked further comment. It was also that New York University was forced to close all its overseas courses as a result of the catastrophic farrago. So many and so varied were the problems encountered by the expedition that the reader barely blinks when the Indiana Gazette is quoted reporting, ‘Bubonic Plague Found on “Floating University”.’

These difficulties were not merely of local concern, irrelevant outside the realm of American academia. An international project, the whole scheme was widely recognised as having global significance. The students were introduced to the king of Siam, Pope Pius XI and Mussolini. Writing of their visit to Japan, however, the American ambassador observed that their behaviour ‘had done more to hurt the relations between the two countries than anything that had happened for fifteen years’.

The great achievement of this book is Pietsch’s use of the hapless Lough and his ill-fated excursion to explore some big and important questions about universities more generally. Wholly aware of just how farcical the Floating University might now appear, she successfully demonstrates the value of taking it seriously as a subject of study. In her hands, it becomes a way of understanding a world in flux and a period of momentous change for universities.

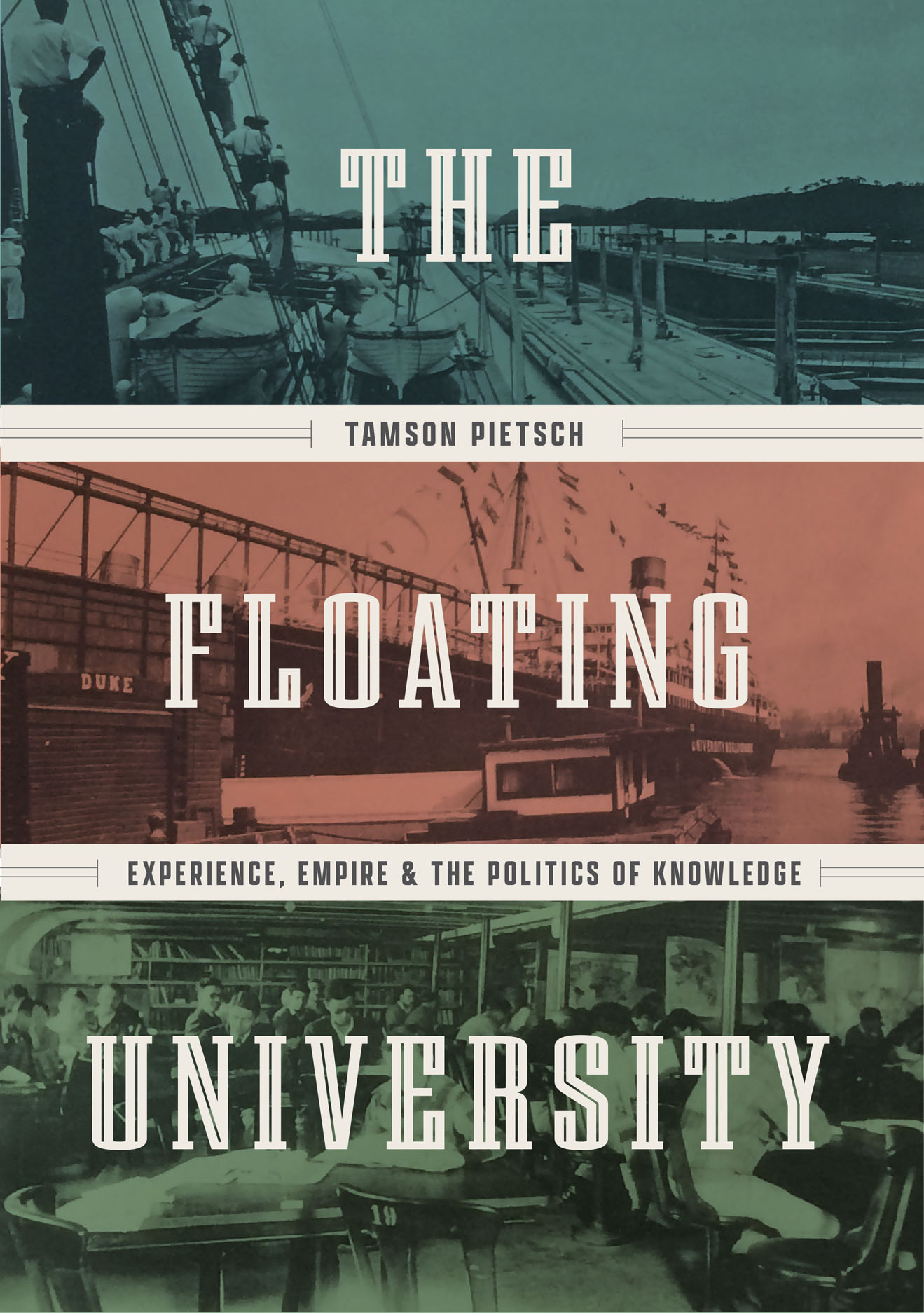

Even the boat itself tells a story. The Dutch-registered SS Ryndam was one of scores of ships looking for a purpose in the 1920s. Originally built to ferry impoverished immigrants to America, it had been refitted for military purposes during the First World War. But postwar curbs on immigration meant that the steamship had no market to return to and needed to find new sorts of passengers. Its transformation into a place of study provides an example of the range of ways in which shipping firms sought to diversify.

More importantly, Pietsch shows that the Floating University emerged out of long-standing debates about the very nature of higher education. Universities typically gained their authority from being the custodians of knowledge. Their libraries and lecture rooms were understood as places where students were granted unique access to truth by their professors. Lough, by contrast, argued that education had no boundaries, that learning by doing was better than simply imbibing the received wisdom of the academy.