The world of invention is famous for its patent disputes. But what happens when your dispute wasn’t with another inventor but whether the Patent Office saw you as a person at all? In 1864, a black man named Benjamin T. Montgomery tried to patent his new propeller for steamboats. The Patent Office said that he wasn’t allowed to patent his invention. All because he was enslaved.

Benjamin T. Montgomery was born into slavery in Virginia in 1819. It’s believed that he learned to read and write from a young age, something not permitted of most slaves because white slaveowners believed that knowledge might lead to rebellions. Montgomery’s literacy gave him a leg up in his later pursuit of everything from surveying to architectural drafting. He even became the first black public official in the state of Mississippi after the Civil War as a Justice of the Peace. But it was his proficiency with machines that would make him notable for the history books—provided mainstream American history books covered such things.

Montgomery invented a number of machines, and documents from the 19th century claim that they involved incredibly high levels of skill to manufacture. But the precise number of inventions by Montgomery has been lost to history. The one invention that we now know the most about was his new propeller for steamboats. He tried to patent it in 1864 but the U.S. Patent Office rejected his application because he was a slave.

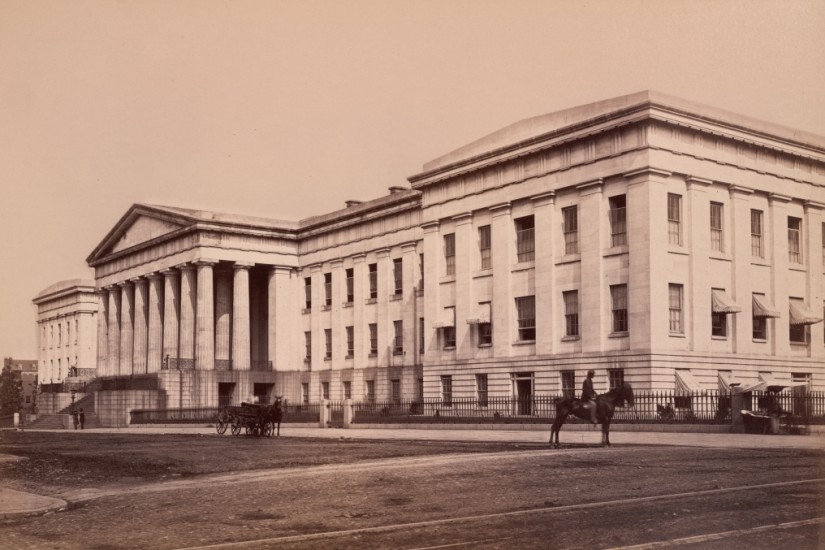

Why would the patent office of the North be so discriminatory against black people during the Civil War? Joseph Holt, head of the Patent Office at the time, was from Kentucky and interpreted Dredd Scott to mean that a free black person who had escaped to the North didn’t have the right to patent his invention. Holt also denied free black men from northern states the same right, despite objections from northern senators like Charles Sumner of Massachusetts.

Benjamin T. Montgomery was sold in an 1837 slave auction to Joseph Davis, the brother of future president of the Confederate State of America, Jefferson Davis. The Davis brothers both lived south of Vicksburg, Mississippi, where they owned large plantations next to each other.

It’s unclear who the first black American to achieve a patent might be for two reasons: The Patent Office didn’t require people to submit their race when applying for a patent, and black inventors would sometimes use white third parties to obtain patents so as not to face discrimination.