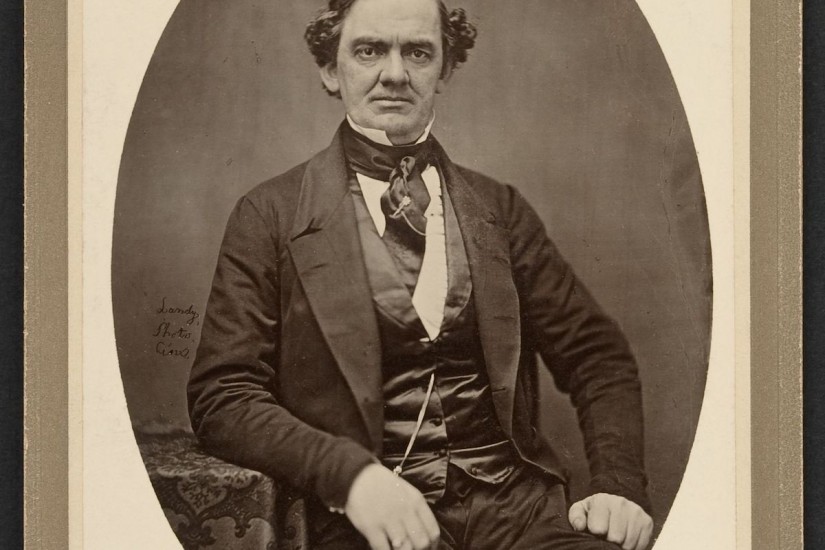

There’s no getting your arms around P. T. Barnum, no safe space in the cultural imagination for this guy. With his jolly bulb of a nose and his limitless energy—that demonic, write-two-lectures-before-breakfast 19th-century energy, historically entitled and unimpeded by neurosis—the great showman grows trickier and more tricksterish with every passing year.

He was a great galumphing racist. He was an unscrupling exploiter of children, animals, and the disabled. He was a caterer to base appetites; his medium was the mob, its whims and its fevers. He was a scammer. Do you sense the approach of a but …? There is no but. Barnum was Barnum, not to be apologized for. Rather there is a series of ands … And he became a devout abolitionist. And he was a generous man who was eulogized at his funeral as “a born fighter for the weak against the strong.” And he entertained millions with his circuses and his American Museum, and with General Tom Thumb and Jenny Lind (the “Swedish Nightingale”), and with his endless caperings in the press. And he had a transcendently disruptive sense of humor, of the sort that cannot help but interrogate, unhinge, and finally overturn the established order.

So if there’s a slightly tense, withholding feel to Robert Wilson’s Barnum: An American Life—if it reads, in a word, rather un-Barnumesquely—it’s not really the author’s fault. A Barnum biographer in 2019 is heavy with consciousness. He feels concern for the people off whom Barnum made his fortune. He is stylistically constrained: “From the perspective of our own time, it seems clear that Barnum crossed the line numerous times.” Or: “This is one of those places in Barnum’s story where a modern sensibility must struggle to understand him.” Wilson is not being mealymouthed. He just can’t go full Barnum. The evolution of human relations and the temper of the hour will not allow it.

And full Barnum is—what? A heavy-metal montage of huge people, tiny people, woolly horses, automatons, jeering crowds, hoops of fire, and whiskey-drinking elephants headbutting oncoming trains, with lighting by David Lynch and dialogue by Monty Python. It’s an education in deceit: the buzz of the put-on, of being hoaxed and knowing you’re being hoaxed and loving it. Being in some dimension flattered by it. Barnum’s word for his art was humbug.