In America, public memory is skewed in favor of “those who were allowed to hold power,” Rebecca Solnit writes in the New Yorker. The country’s landscape is dotted with tributes to dead white men—many of whom fought to subjugate those with skins darker than theirs.

The Southern Poverty Law Center estimates 1,500 monuments, public buildings, and military bases around the country invoke the Confederacy—largely erected during spurts of racial progress and thus, in direct opposition to it. Meanwhile, the spaces where enslaved people and their descendants were tortured and killed largely go unmarked. And public monuments to their resilience and struggle for justice are too few and far between—particularly in the South.

But it’s not just structures that skew in favor of Confederate history in the South.

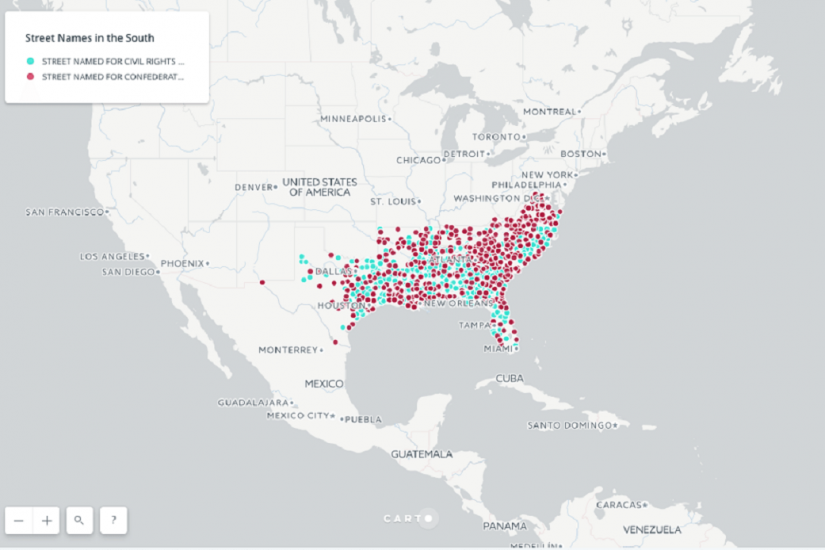

Two new maps created by Caroline Klibanoff, a digital public historian at Northeastern University, document street names. In the first, she tallies the number of streets named after Confederate leaders alongside those celebrating prominent figures from the civil rights era.

In the U.S. overall, the latter outnumber the former—but that flips in the South (first map below). While this map doesn’t necessarily offer a comprehensive count, it allows for a comparison of how the two historical occurences are regarded, remembered, and enshrined, Klibanoff writes:

The map shows variations among the former Confederate states; Virginia, home to several Civil War battlefields, contains far more Confederate-named streets, for example. Whereas in Alabama—where the Montgomery bus boycott took place, where Freedom Riders fighting segregation weathered the worst spates of violence, and where Martin Luther King, Jr. led the march from Selma to Montgomery—civil rights commemorations outweighed the Confederate ones.