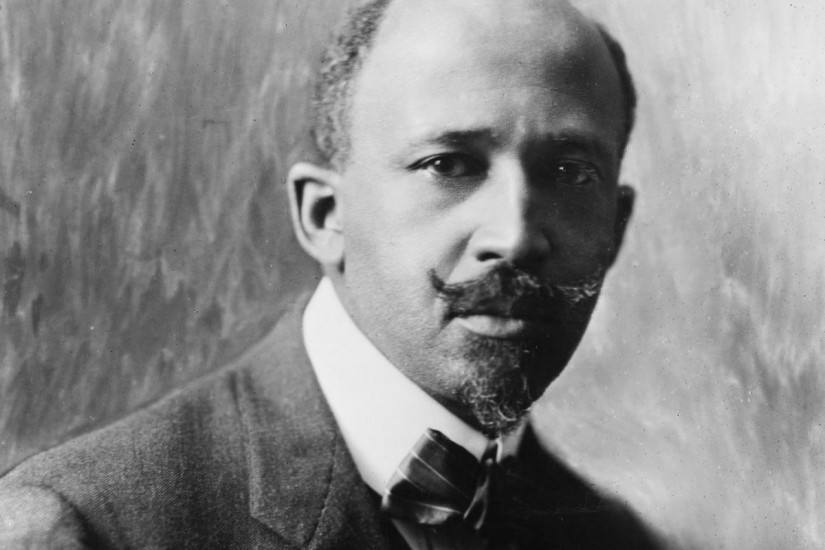

In publishing The Souls of Black Folk, on April 18, 1903, Du Bois argued, implicitly, that the world needs to know the humanity of black folk by listening carefully to the “strivings” in their souls. And we can hear in the book the strivings in the soul of Du Bois as much as we can hear the strivings in the souls of other black folk. We hear about Du Bois’s racial worldview (essay one: “Of Our Spiritual Strivings”). We learn of his ideological problem with Booker T. Washington (essay three: “Of Booker T. Washington and Others”). We take in his college-age experiences as a schoolteacher in rural Tennessee (essay four: “Of the Meaning of Progress”). We come to understand his personal loathing of Atlanta’s greed (essay five: “Of the Wings of Atalanta”). We hear his plan for the Talented Tenth (essay six: “Of the Training of Black Men”). We read about his perspective on the impact of slavery on morality (essay nine: “Of the Sons of Master and Man”). We cry with him as he buries his firstborn son (essay eleven: “Of the Passing of the First-Born”). We learn about one of his idols (essay twelve: “Of Alexander Crummell”). We cry again during his tragic short story about an educated black man demolished by racism (essay thirteen: “Of the Coming of John”).

But Du Bois’s soul reflected many souls. Many could personally relate to John in “Of the Coming of John.” Many idolized Alexander Crummell, the founder of America’s first black intellectual society. Many buried their firstborns in the cemetery of 1890s racism. Many believed slavery had destroyed morality. Many looked up to the Talented Tenth. Many loathed Atlanta’s gold rush. Many knew about those rural schoolhouses. Many had problems with Booker T. Washington. These essays touched readers in 1903 and beyond, and harmonized with Du Bois’s more scholarly but no less lyrical essays on the Freedmen’s Bureau (essay two: “Of the Dawn of Freedom”), on “the massed millions of the black peasantry” (essays seven and eight: “Of the Black Belt” and “Of the Quest of the Golden Fleece”), on African American religion (essay ten: “Of the Faith of the Fathers”), and on African American spirituals (essay fourteen: “The Sorrow Songs”).

Much as Du Bois’s soul reflected those of others, though, it remained uniquely his. Like all souls, it is poetic, and The Souls of Black Folk speaks to humanity like one long poem. In order to understand this long poem and why Du Bois wrote it when he did, we must understand the major ideas, events, and forces that nurtured it, particularly the power of “the Veil.”