Why should we care about “the Trial of the Century” nearly a century after it happened? Many Americans have long understood the 1925 prosecution of John Scopes in Dayton, Tennessee, for breaking a new state law that forbade teaching “the Evolution Theory” in public schools as a conflict of profound simplicity in which religious bigotry clashed with scientific reason. In it, Clarence Darrow, a veteran stalwart of the legal left, skillfully defended Scopes, a biology instructor, while William Jennings Bryan, a thrice-failed nominee for president and devout fundamentalist, clumsily led the case for the state. The trial was broadcast to the entire the nation over an enterprising radio hookup.

Since Scopes freely admitted he had done the deed as charged, the guilty verdict came as no surprise. But what the court case achieved was something else: After Darrow put Bryan on the stand and humiliated him by exposing his lack of curiosity about both evolution and the Bible, many who had followed the trial concluded that the defense had won that round of the culture wars. The peerless and pitiless H.L. Mencken attended the trial and was among them: He hissed to his many readers that Bryan was “deluded by a childish theology, full of an almost pathological hatred of all learning, all human dignity, all beauty, all fine and noble things. He was a peasant come home to the barnyard.” The 1960 film Inherit the Wind powerfully dramatized that opinion for countless kids (like me) who saw it in liberal classrooms and on TV during that decade and beyond.

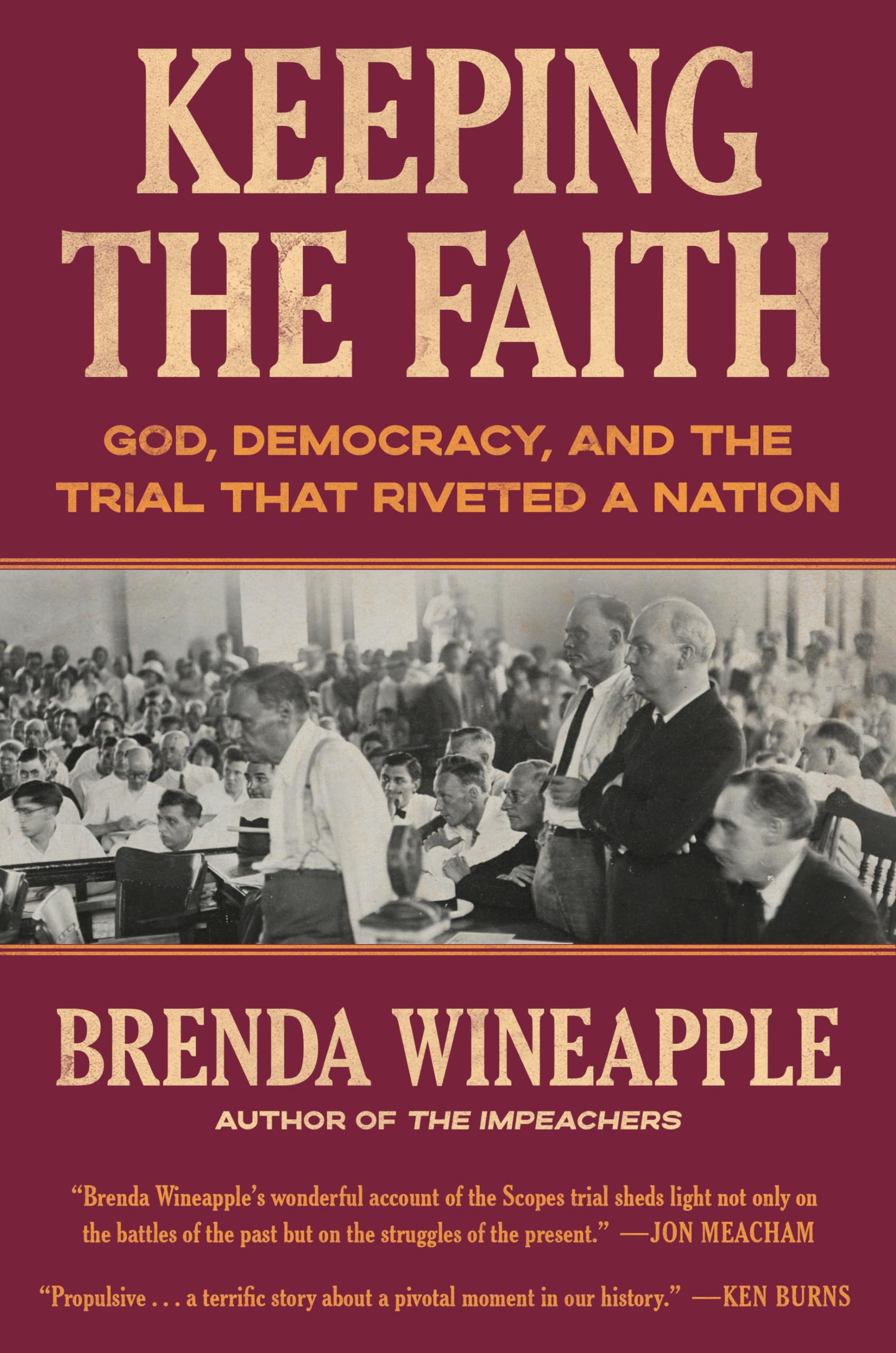

In her new history of the trial, Keeping the Faith, Brenda Wineapple freshens this familiar narrative and suggests that something different, if equally momentous, was at stake during the weeklong proceedings at a redbrick county courthouse in the foothills of the Appalachians. While arguing about the Butler Act, the state law that censored the teaching of biology, each side was also setting forth a firmly held conception of democracy. “To Bryan,” Wineapple writes, “democracy meant majority rule and states’ rights. The people in each state should decide for themselves…what should be taught in state-supported schools.” But for Darrow, “there could be no democracy without reason, which is to say, without education and an educated people.” They fought for their clashing faiths in democracy at the court and everywhere newspapers were read and radios heard. Each man and his allies feared for the nation’s future if they could not persuade the public to take their side. And it is hard not to hear the echoes of a contemporary conflict in these fears as well: between citizens who demand a set of policy measures to “make America great”—and Christian—“again” and those who believe that civic tolerance and the freedom to speak and teach the truth are what give Americans the potential to live up to the nation’s vaunted, if abstract, ideals.