What resulted in 1954 was Northland Center, a new kind of semi-enclosed commercial space where beautiful art—sculptures and landscaping so striking that a New York gallery exhibited the corresponding sketches and models—and the intense aesthetic regulation of stores came together to turn shopping into a form of entertainment. This effect, in which you come to the mall to buy one thing and find yourself in such a lovely mood that you end up buying a whole bunch of other things, became known as the “Gruen transfer,” and it changed the way we shop. Gruen’s concept opened up the space to other businesses, too; they could all gather in one palatial compound. Northland Center was soon fully leased, and a horde of enthusiastic consumers meant that the venture made a lot of money for Webber —and likely for the retailers as well. The Gruen transfer helped encourage people to spend, spend, spend, and it looms almost as large as any building in the architect’s legacy.

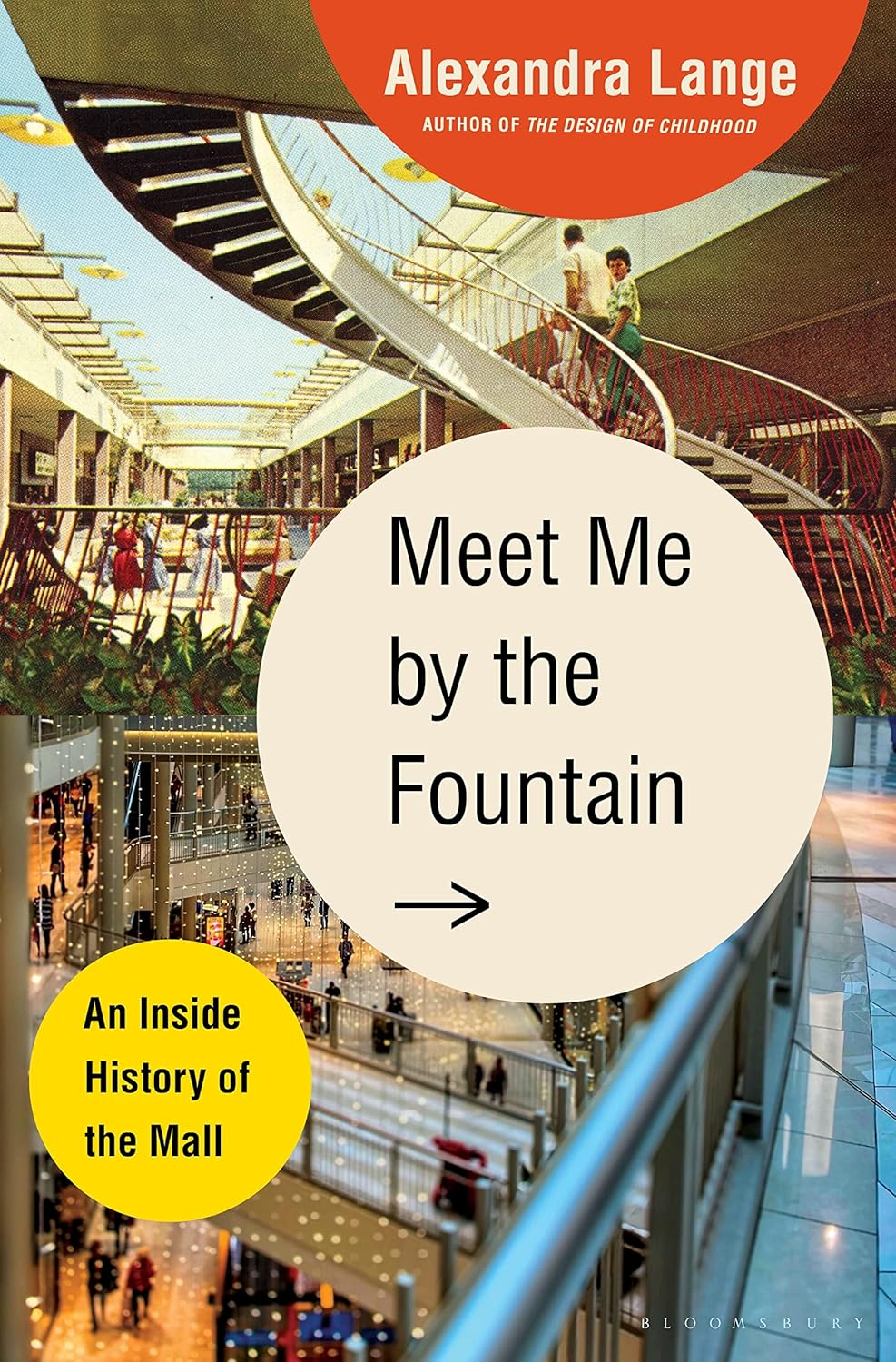

In Meet Me by the Fountain, a new history of the mall by Alexandra Lange, we learn a great deal about Gruen and all the further innovations built upon his handiwork in order to increase the amount of money squeezed from mallgoers. After we meet America’s Mall Daddy, we’re introduced to the mall’s first family, the Nashers of Dallas, who in 1965 constructed NorthPark Center, a gleaming white monument to Texas luxury, where art, curation, and aesthetic discipline again united to create a powerful draw. The Nasher family purchased heaps of artwork for their mall, including a giant Beverly Pepper sculpture that was “designed to be admired from a car in motion,” Nancy Nasher told the Dallas Morning News. “Drive by and see it. Then park and come in.” The mall’s sizable staff, led by a design director who hovered over details as small as the comfort of a store’s seating, constantly preened and primped NorthPark, searching for ways to keep customers mesmerized and refreshed. From Northland to NorthPark, if you want to pull thousands of people miles away from their homes for the pleasure of parting with their money, you had better make the experience worth it.

But Gruen and his forebears could not have predicted what the mall would become, something Gruen himself admits in his memoir: “Shopping centers were initially successful because they were designed on the basis of idealistic motives. But now they have simply become too successful, in the same way the car has become too successful. They are so overwhelming that nothing is able to restore the balance.” This contradiction sits at the center of Lange’s book: The mall is beautiful and soothing, but its pursuit of profit steers it away from truly serving us.

Lange’s previous book, The Design of Childhood, focused on the ways that playgrounds and other built environments shape the behaviors of young people, and Meet Me at the Fountain similarly swings its focus between the buildings that house the shopping to the people who do the shopping: She draws our eye to the constant presence of children on the plinths and pools of a fountain outside the Neiman Marcus store at NorthPark. But she also dives into the ways that people use malls outside of commerce. The Nashers, for instance, project civic magnanimity by opening up NorthPark for public use, including a children’s branch of the Dallas Public Library and Lunar New Year celebrations.