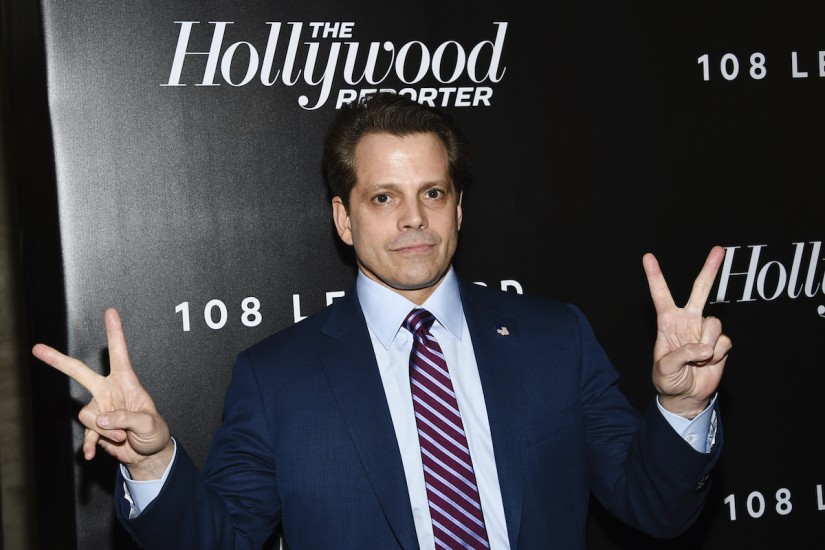

Anthony Scaramucci lasted 10 days as President Trump’s White House communications director. He’s hoping to last a little longer at his next gig: a contestant in the new season of “Celebrity Big Brother.”

Scaramucci won’t be the only person in Trump’s orbit with a “Celebrity Big Brother” credit to his name. Omarosa Manigault Newman, who became a household name during her turn on “The Apprentice” 15 years ago, also starred on the show. Energy Secretary Rick Perry took a turn on “Dancing with the Stars,” as did Tucker Carlson. And of course, the president himself has a reality TV past.

In the Trump era, cable news programs aren’t the only places where politicos go to secure lucrative contracts that capitalize on their White House exposure. In many ways, this other type of revolving door is not new. Over the past 70 years, entertainers have made their way into politics — and back into entertainment — in ways that have reshaped both worlds. This collaboration has resulted in a dramatic shift in political values, creating a culture in which those who entertain us and those who lead our public affairs have become one and the same.

Given this link, and the unique tenor and tone of reality television, the fact that figures from the divisive, norm-shredding Trump administration are migrating to this platform is not surprising. This particular type of entertainment helped pave the way for Trump’s presidency, and now producers are cashing in on his discarded cast.

It was Dwight D. Eisenhower who first recognized the benefits of recruiting personnel from the entertainment industry. Aware that television, a relatively new technology, was gaining a following in America, Eisenhower brought actor Robert Montgomery into the White House as his television adviser. A longtime Republican, Montgomery was eager to share his expertise on camera angles, makeup and on-camera performances with the new president, who lacked experience with television. Together, they created a production studio in the White House and ushered in a “prime-time presidency,” in which Eisenhower relied on television not just to win campaigns, but also to govern.

The White House position gave the aging actor relevance in both realms. He hosted the television show “Robert Montgomery Presents” until 1957, using it as a platform to boost Ike’s reelection in 1956. When he left the White House, his film career faded, but he attempted to remain relevant by penning a book with insights from the two worlds his career had straddled. In his “Open Letter From a Television Viewer,” Montgomery explained the importance of television to democracy, and then critiqued the growth of network power and the way it threatened civic life by limiting programming options. By appealing to the “lowest common denominator,” lamented Montgomery, networks believed “people are basically too undiscriminating and of too low taste to want or deserve anything” else.

What Montgomery saw as a problem in entertainment, however, the GOP viewed as political opportunity.