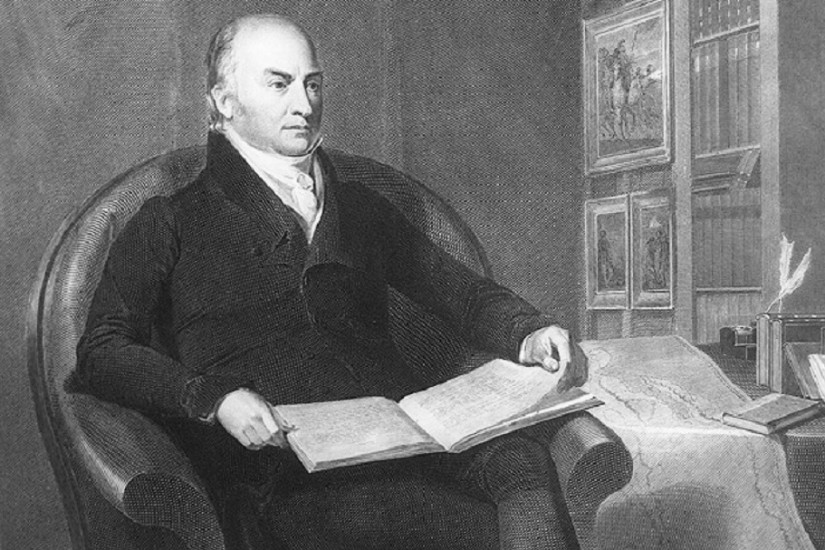

July 11 is the 250th anniversary of the birth of John Quincy Adams. We are experiencing something of an Adams revival, with several new biographies, new editions of his astoundingly revealing and eloquent diary, and a renewed willingness to see this one-term president turned antislavery congressman—rather than his ally-turned-rival Andrew Jackson—as the custodian of what is most redemptive, and hopefully enduring, in the American political tradition.

Is it a simple matter of Jackson down, Adams up? Or is it Jackson red, Adams blue? During the waning days of the Obama administration, the Treasury Department, under pressure to diversify the faces on currency, decided to save Hamilton and Franklin but give up Andrew Jackson in favor of Harriet Tubman. Not at all coincidentally, candidate and President Trump awkwardly embraced the white populist legacy of Jackson, imagining Jackson (dead in 1845) as a “winner” who might have prevented the need for a Civil War.

This string of quotes and tweets led to a lot of handwringing among historians who identified good reasons to see the Trump in Jackson: Both shared a hatred of Washington, made outsized claims to mandates, took quick action to remove undesirables (in Jackson’s case, southern Indians), flaunted a willful ignorance of precedent, embraced crony capitalism, and relied on sheer bluster, whether cynical or sincere. Other experts and pundits defended Jackson, citing his extensive experience as a military leader, his democratic bona fides, and his principled stance against banks and South Carolina nullifiers.

But there’s more to Adams’s revival than Jackson’s fall. The junior Adams used to be ridiculed as an aristocrat so stuck in his parents’ 18th century that he refused to stick with a political party or campaign for the presidency. But no one, including Jackson, can best his half-century of public service or the sheer variety of his contributions as a legislator, executive, and diplomat. Without question, he was the most experienced statesman ever to occupy the Oval Office.

How did Adams survive so long in national politics? It wasn’t his famous name. And it certainly wasn’t the antislavery credentials we celebrate now. While his father John Adams has recently gained an exaggerated reputation as an antislavery founding father, the son knew better: John Adams had actually helped tamp down slavery issues in the Continental Congress and never tried to resuscitate them as vice president or president. It was in part by hewing to other principles—his nationalism above all, and next his ambition—and practicing bipartisanship, joining with Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans during the debate over the Louisiana Purchase and then fully switching parties during a controversy over international trade regulations. Punished by his Massachusetts colleagues, who declined to renominate him for the U.S. Senate, at the age of 41 he turned down a Supreme Court seat and instead packed his bags, his wife, and oldest son off to join him at a diplomatic post at St. Petersburg.