In the end, it was American racism—which genuinely pained him—that brought out the distinctive best in Kempton. Writing from the South in the 1940s and ’50s, he achieved true eloquence; the pieces he wrote then are remarkable for the way in which he trusted them to tell their story through spare, novelistic evocation rather than overwritten, rhetorical indignation. For example, here’s a Black woman overheard on a bus: “An’ then Ah went in the white section to get a drink, an’ this big white man says so meanlike ‘Git back on your own side, sister’ and it was dirty and they had a little ole hole to pass the water through.” A white man speaking from his car: “Lissen, mister, I’ve lived in this country thirty eight years an’ if you find an honrable darky, there ain’t nobody better, but you get a mean one, there’s nothing else to do but shoot him.”

Or Kempton describing a Black witness during the Emmett Till trial: “His tongue forced him to the wildest piece of defiance a Delta Negro can accomplish; he stopped saying ‘Sir’ and began answering [the defense attorney’s] every lash with a ‘That’s right’ which was naked at the end,” the man clearly enduring “the hardest half hour of the hardest life possible for an American.”

On the unblinking courage of Autherine Lucy, the Black student chosen in 1956 to integrate the University of Alabama, where she was all but stoned, Kempton writes: “This is what William Faulkner was talking about when he said of the Delta Negro that he endured. Through poverty, shame, and degradation he endured.”

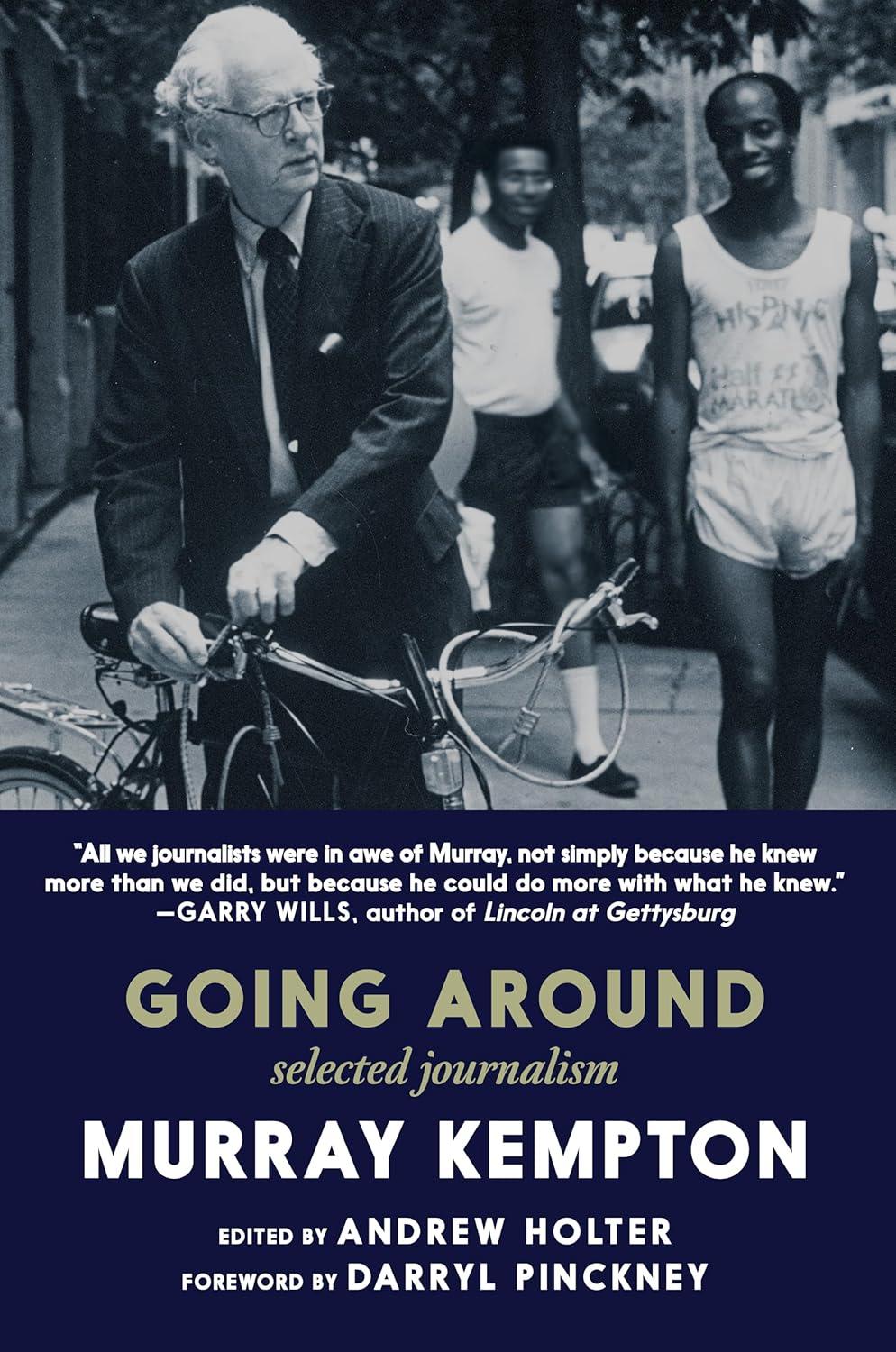

For the most part, Kempton stayed put in Manhattan, where on any given morning he could choose to cover a demonstration at City Hall, a mobster’s funeral on Mulberry Street, an Albanian parade on Fifth Avenue, a dance rehearsal in Harlem, or a gay activist picketing a restaurant in Chelsea. Throughout the week he’d consult the wire services, make a mental list of which events to cover, button up the jacket of his venerable three-piece suit, get on his bike (he never learned to drive), and spend the day “going around.” In the evening, he sat down to write tomorrow’s column, the beating heart of which would be an account of the built-in inequities that thwart fairness and decency at almost every turn.