Although the title “The Man Who Hated Women” refers to Comstock, Sohn’s book is not a biography, and that’s all to the good; there are solid, recent biographies of Comstock out there already. Sohn, a novelist—this is her first nonfiction book—focusses instead on some of the women who resisted Comstock and his law, offering an alternative history of feminism and of the free-speech movement in America. There were certainly men who fought against Comstockery—outspoken journalists and a host of lawyers who defended banned works of literature and sex education against bluenosed censors. But Sohn points out that the women who did so were especially brave, since many of them were persecuted and prosecuted under the law at a time when they did not have the vote and could not serve on juries—and when a lady who spoke openly about sex might be assumed to have gone mad and be treated accordingly.

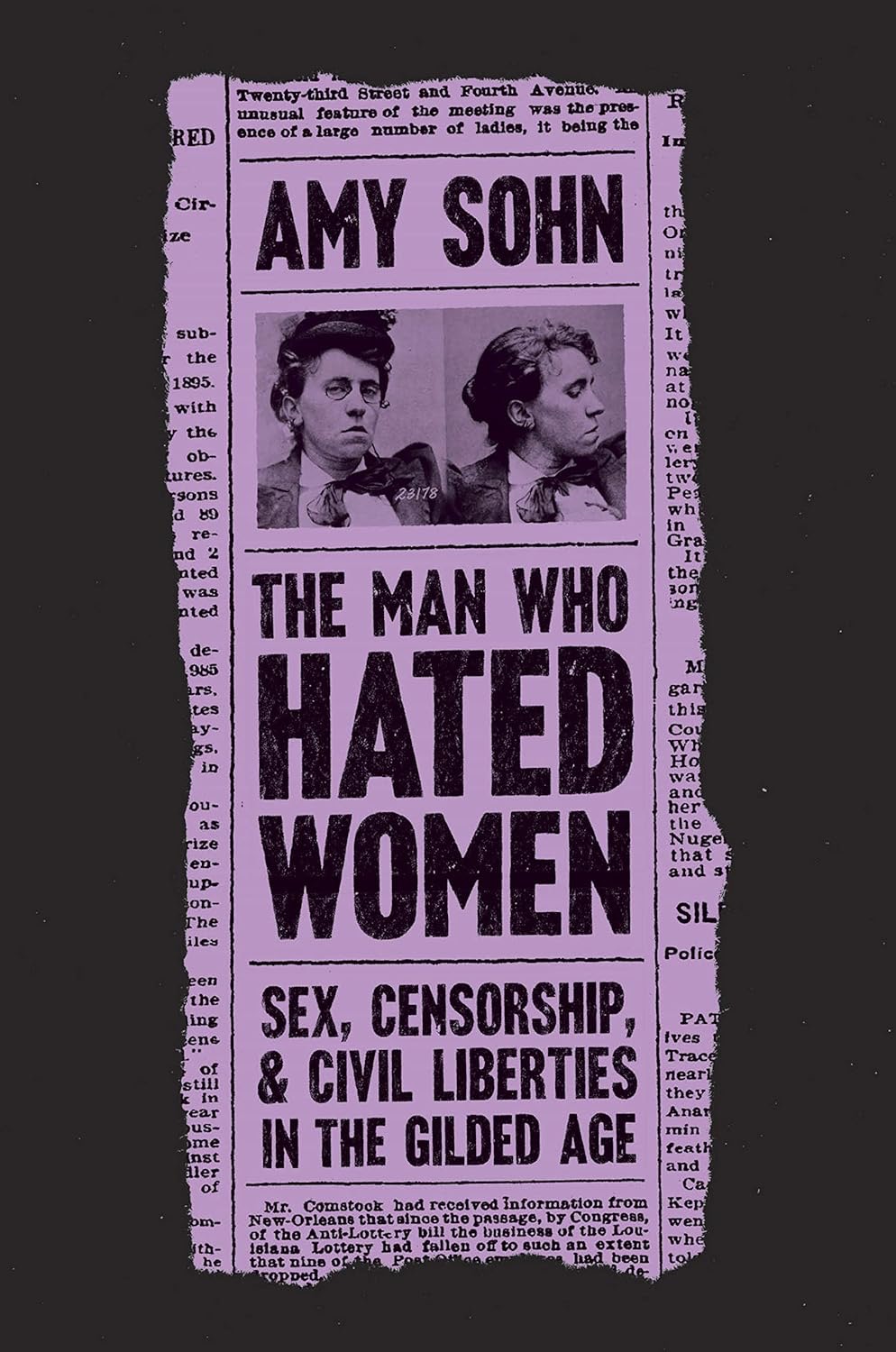

A few of Comstock’s targets who feature in Sohn’s book are well known—Margaret Sanger, Emma Goldman—and many readers will know, too, about Madame Restell and the flamboyant suffragists, newspaper publishers, and stockbrokers Victoria Woodhull and Tennessee Claflin, Woodhull’s sister. But the others are likely to be much less familiar—they are the deep cuts, sexual freethinkers left aside by most social histories of the era. “Despite their extraordinary contributions to civil liberties,” Sohn notes, most of these “sex radicals have been written out of feminist history (they were too sexual); sex history (they were not doctors); and progressive history (they were women).” These are good explanations, but there is another one: their essential weirdness. They’re like the outsider artists of activism, creating their own unschooled, florid, and enraptured works of protest. Reading Sohn, I grew quite fond of them.

Angela Heywood, for instance, was a working-class woman from rural New Hampshire who, with her husband, Ezra, became a public advocate for “free love,” which they defined as “the regulation of the affections according to conscience, taste, and judgment of the individual, in place of their control by law.” The Heywoods sound at times like a contemporary couple who might have met at an Occupy demonstration and settled down in Brooklyn doing something artisanal. Before they married, Ezra had left his graduate studies at Brown to become a travelling antislavery lecturer. Angela supported the abolitionist movement as well, and held a series of odd jobs. The Heywoods, who put down stakes in central Massachusetts, were happily monogamous, but believed that the institution of marriage should be reimagined on more egalitarian terms. They denounced debt and wanted to disband corporations. They also published frank guides to conjugal relations and a journal, which brought them to the attention of Comstock, while operating a tasteful, rustic inn where one of their young sons, Hermes, ran around in girls’ clothes.