It was a moment of turmoil, when a school became a lightning rod for debates about American values and the Constitution. At the center of it all was a clutch of students, their teenage faces beamed across the country by television cameras. But no sooner had they emerged as heroes than they were branded as phonies.

The year was 1957.

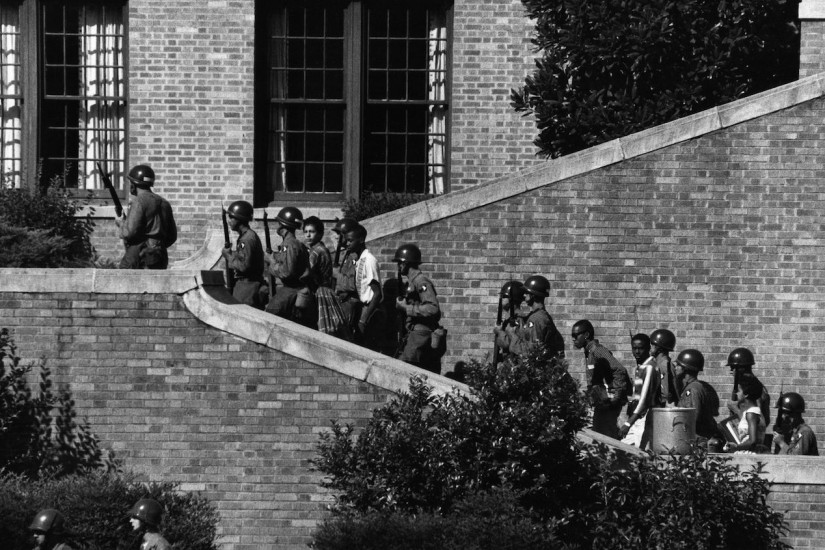

Sixty-one years before teens at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., would survive a mass shooting only to be labeled “crisis actors,” the nine African American teens who braved racist crowds to enroll in Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas were also accused of being impostors.

False rumors that the Little Rock Nine were paid protesters even forced the NAACP to issue a statement condemning the stories as “pure propaganda.” The students were not, in fact, “imported” from the North, said the NAACP’s Clarence A. Laws, but rather the children of local residents, including veterans.

When Princeton history professor Kevin M. Kruse pointed out the parallel between Parkland and Little Rock earlier this week, his tweet went viral.

“It’s funny,” Kruse told The Washington Post on Thursday. “I’m teaching a class right now that does deep dives into three historical moments as a way to teach students how to use documents, and the first one we’re doing is on Little Rock. … So when the ‘these students must be paid’ thing came up in the news, it took me a day and then I was like, wait a minute, I just read about this.”

But the practice of dismissing witnesses to major historical events as mere paid actors goes back much further than the Little Rock Nine.

“It’s a theme that crops up throughout civil rights history,” said Kruse. “Back then, it was an assumption that African Americans in the South couldn’t possibly be upset. They must have been stirred up from the outside, either paid to do this or inspired to do this by propaganda. They couldn’t have come up with this on their own.