By exposing the fiscal side of white supremacy, The Black Tax recasts Jim Crow as not just a racial system, but an economic one. Over the last decade, scholars including N. D. B. Connolly and Matthew Desmond have shown how racial discrimination—far from being “counterproductive” or “inefficient” from a market standpoint—creates profits, fuels exploitation, and enshrines material inequality. For African Americans, the experience of second-class citizenship was not merely “the indignity of being forced to drink from a ‘colored’ water fountain.” Rather, segregation also ensured that resources extracted on one side of the color line were hoarded on the other. Some Americans enjoyed paved streets, routine trash collection, and working fire hydrants, Kahrl shows, because others were denied these things.

In many places, not much has changed. Under “fiscal apartheid,” Black Americans from Baltimore to Ferguson, Missouri, are denied the mundane infrastructure and essential services that protect and maintain human life—public goods their taxes also pay for. Yet this injustice has always inspired fierce and creative forms of resistance. “Wherever Black people secured a measure of local political power, a fight over tax and spending practices and priorities ensued,” Kahrl observes. One of the book’s best chapters details how Black mayors such as Coleman Young in Detroit and Chicago’s Harold Washington pledged to hike taxes on corporate landowners, only to embrace neoliberal austerity under pressure from bondholders and white flight.

One hundred and fifty years on, how does fiscal apartheid end? A careful historian, Kahrl hesitates to present any sweeping solutions or panaceas in the present. No single set of reforms will fix “the inequitable distribution of public goods” or repay the hundreds of billions owed to Black Americans. Instead, he outlines a few ways to narrow the racial economic divide, such as raising taxes on the “one percent” and standardizing the homeowner property tax exemption. Though some readers may leave wanting a more detailed policy vision, The Black Tax should be received as a call to arms: a searing indictment of American racism and inequality in black and red ink.

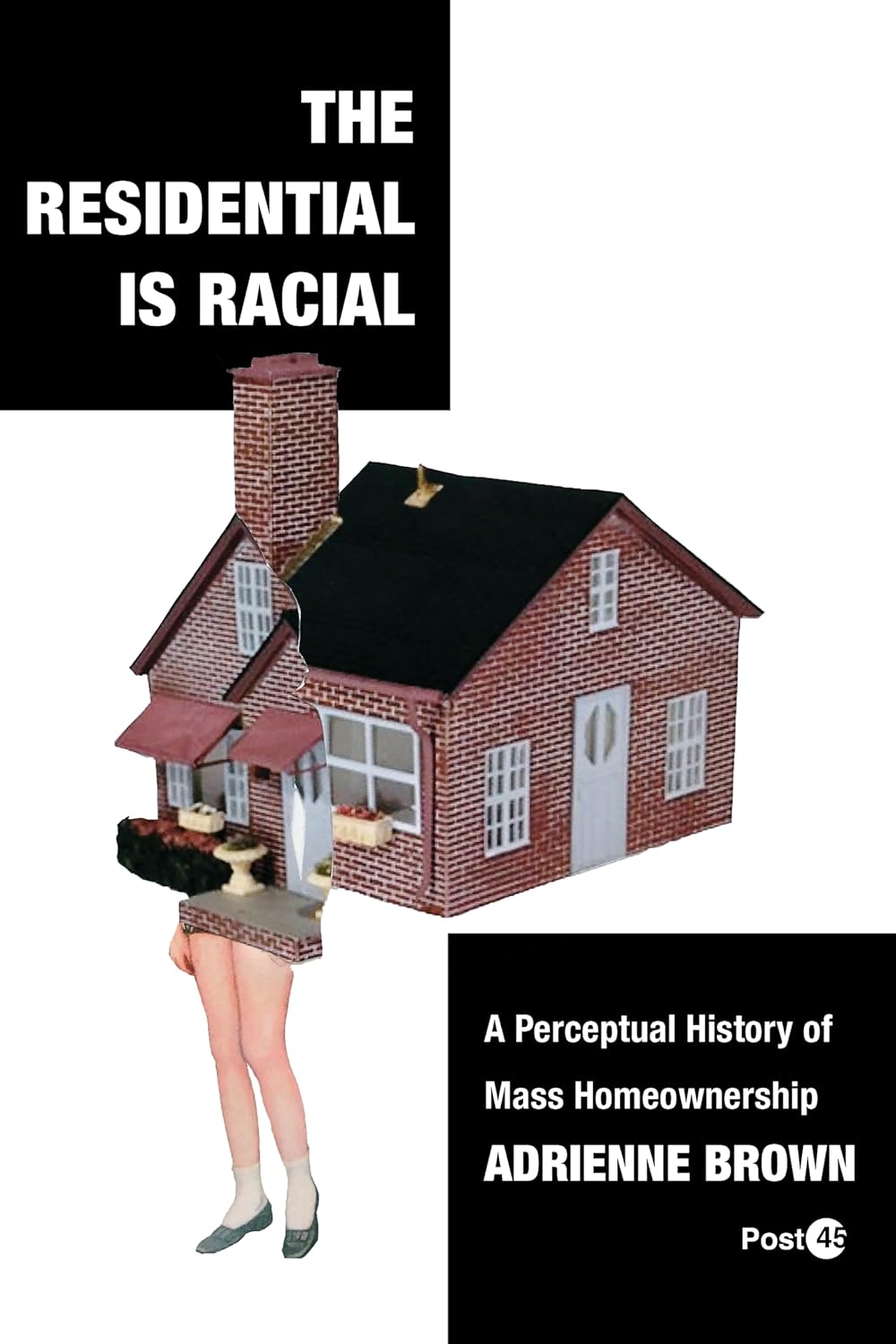

Where The Black Tax shines a light on the hidden fiscal machinery of US apartheid, Adrienne Brown’s The Residential Is Racial reveals how literary and print culture made racist housing policies appear both natural and desirable. While urban historians still debate the precise ways that racism segregated America, Brown turns the question on its head. She asks, instead, how did the rise of mass homeownership change popular perceptions of race? And why does the idea of “residential living” project such a powerful allure?