In The People’s Porn, Lisa Z. Sigel, a professor of history at DePaul University in Chicago, is interested in a very particular kind of artifact: the homemade pornographic object. Antiques like scrimshaws “represent the consciousness of their makers and allow us to generate an idea of a past world,” she writes, hurling these tchotchkes into anthropological legitimacy. Sigel focuses on provenance, rarity, materiality, and the individual consciousness behind the handmade, and applies this way of looking to the gamut of amateur pornographic objets, from erotic gewgaws from the nineteenth century to works considered to be modern “folk” or outsider art, to various forms of erotica just up to the age of the camcorder.

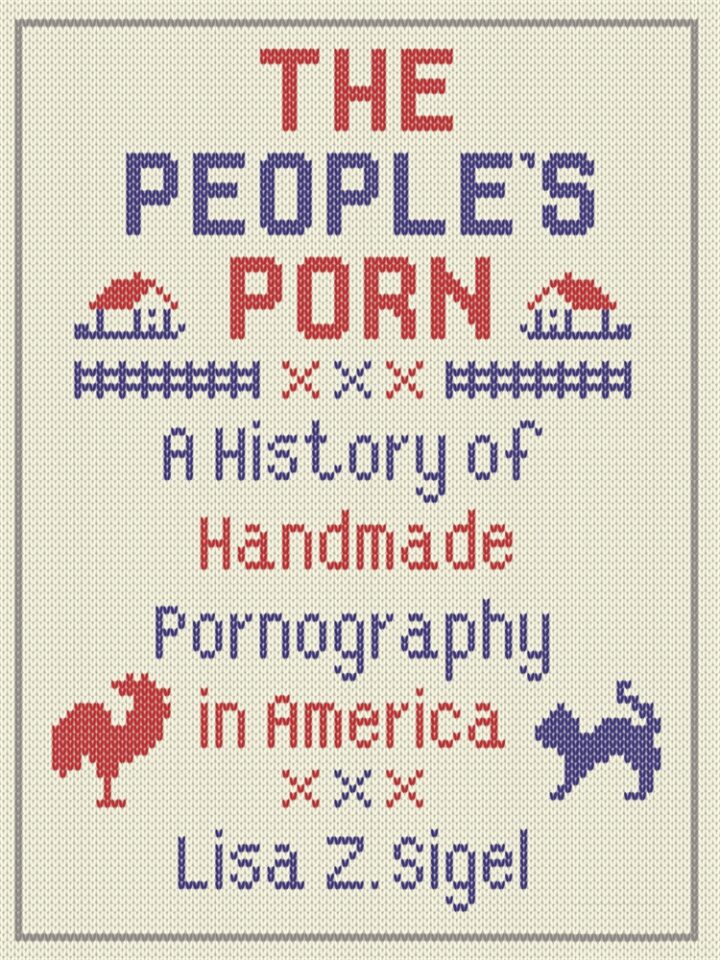

Sigel has previously published three books in the discipline of sexuality studies, each with mildly naughty, confectionary titles: Governing Pleasures: Pornography and Social Change in England, 1815–1914 (2002); International Exposure: Perspectives on Modern European Pornography, 1800–2000 (2005), which she edited; and Making Modern Love: Sexual Narratives and Identities in Interwar Britain (2012). In The People’s Porn, she is committed to seeing cultural meaning in objects that scholars have largely ignored—regardless of whether they ought to be seen as simple masturbation material, items of psychosocial or political defiance, or possibly something more sinister, like incitements to commit sex crimes.

One reason pornographic artifacts have yet to achieve a legitimate status in science, art, and academia—apart from their marginalization from polite society—is that so much of their history is impossible to retrieve. Unless pornographic materials found their way into private collections, they were routinely destroyed to prevent prosecution, scandal, or embarrassment. (Politics aside, most masturbation aids are not viewed as having social or historical value but as sticky, disposable gross-outs of questionable provenance.)

Various moral codes have banished masturbation and erected stigma; the Victorians, for instance, officially turned such a piercing eye on the act of self-love that masturbation was seen as a serious and even potentially fatal threat to mental and physical health, a cause of insanity and syphilis alike. In the United States, obscenity trials in the nineteenth century—thanks to “anti-vice” activists like Anthony Comstock—caused innumerable pornographic objects and other sexually explicit material (including information about contraception) to be seized and burned.

Unveiling the surviving objects from the hypocritical shroud of prudery, Sigel argues, will help us understand our fellow man and woman. “These objects—in all their incoherent, libidinal, confusing strangeness—remain acts of individual testimony that can and should be entered into the historical record,” she writes. “They tell us about how people understood sexuality through what they could visualize.” They also, Sigel demonstrates, were a way for anti-establishment, antisocial attitudes to be articulated via explicit sexuality or deviance—a crudely drawn dingus being, in essence, a middle finger to the status quo.