The People vs. Agent Orange makes painfully clear that the story of 2,4,5-T and other dioxins, a class of chemical compound described by one interviewee as inflicting an all-out “assault on the human genome,” is far from over. In 1983, Van Strum’s lawsuit led to a total ban of 2,4,5-T; the other key ingredient of Agent Orange, however, remains on the market. And while post-9/11 veterans were never exposed to this toxic herbicide, many have become sick following exposure on their bases to burn pits that spewed the same dioxins. Like numerous other chemicals, dioxins are by-products of industrial processes—waste incineration, for example, or paper processing. Consequently, they’ve been viewed as inevitable, even negligible, side effects of American capitalism and military primacy. Today, the Environmental Protection Agency views dioxins as among the most dangerous pollutants on the planet, and regulators have cracked down on their production. But because of their once-prolific production and two-billion-year half-life, dioxins, at this point, can be found in all the earth’s elements: soil, water, air, and fire.

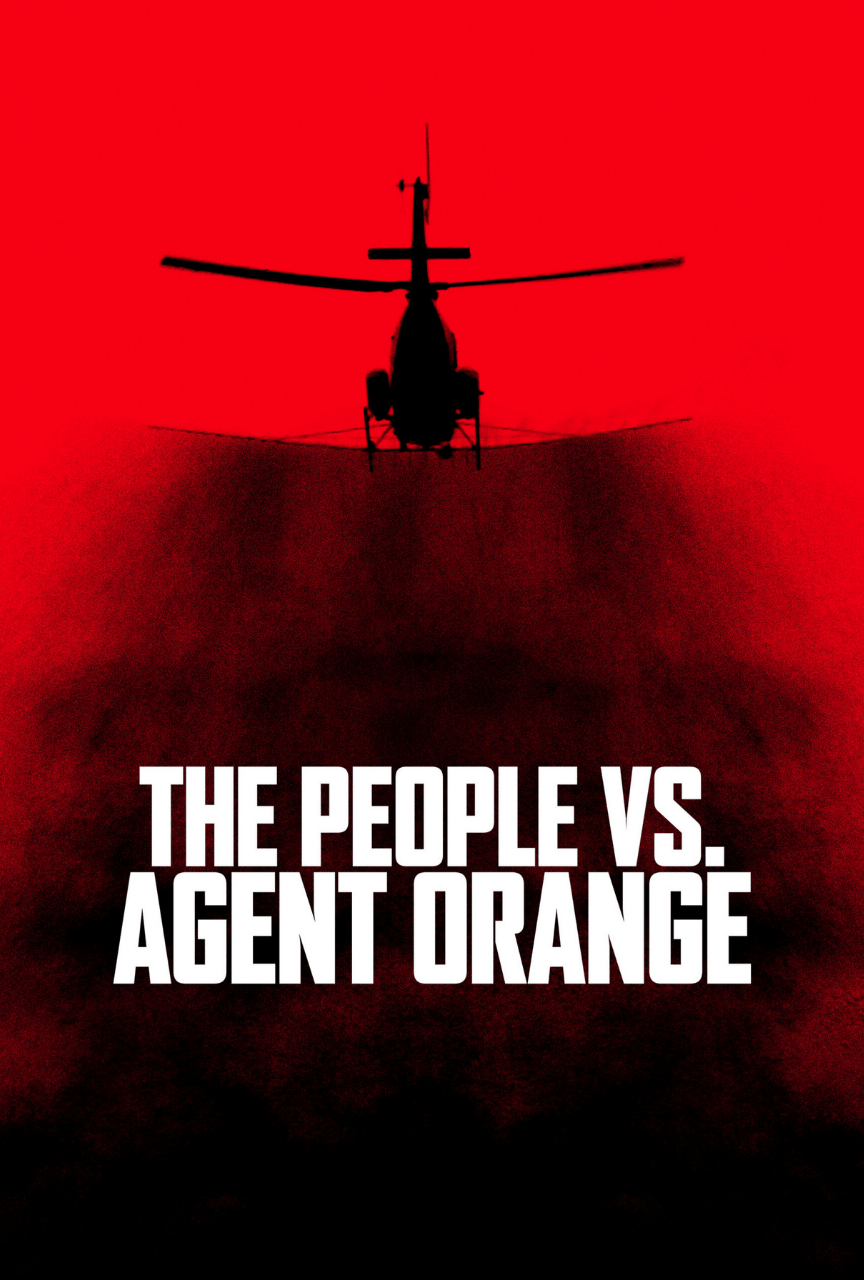

How has such a vast poisoning gone practically unnoticed by the public? The People vs. Agent Orange describes a concerted campaign of misinformation, legal muscle, and dirty tricks on the part of the chemical industry to avoid scrutiny and shirk liability. And indeed, willful ignorance or outright malfeasance accompanied the use of Agent Orange from practically the beginning. In Operation Ranch Hand, which kicked off in 1961, soldiers sprayed nearly 20 million gallons of the herbicide across Southeast Asia. (To accomplish this mission, the U.S. government essentially federalized the chemical companies Dow and Monsanto to produce endless drums of the stuff.) A National Security memo from the time described Ranch Hand as a plan that would kill two birds with one stone: It would at once deny cover to the enemy and deny them food. Quite quickly, however, troubling third- and fourth-order effects emerged, from rashes and rare cancers to birth defects. And just as quickly, the evidence was quashed.

In fact, scientists raised grave concerns about Ranch Hand as early as 1964. In February 1967, 5,000 of them, including 29 Nobel laureates, presented a letter to President Lyndon Johnson demanding he stop what they considered a barbaric form of biowarfare. And in May 1971, an Air Force scientist, Dr. James Clary, completed a stunning report on the herbicide campaign that indicated serious health problems for many exposed to Agent Orange. “I finished my report, and it was immediately classified ‘Secret,’ and the government kept it locked up for over 35 years and denied that it even existed,” Clary contends in the film. “It was tantamount to a cover-up,” adds former U.S. Senate Majority Leader Thomas Daschle.