IT ISN’T ALL that hard to explain what happened on January 6. The proof reads right off the page. At a rally with thousands of his supporters, President Donald Trump told his people to march to the Capitol; his people went to the Capitol. His son and campaign surrogate Donald Trump Jr. told them to fight; they fought. The case for incitement is on record; or as Trump adherents repeated ad nauseam during the last impeachment: “Read the Transcript!” Yet what is much harder to explain and what future historians are likely to puzzle over is exactly how we got here — how so many Americans could not only believe conspiracies as loony as #StopTheSteal and QAnon, but could also believe them so fervently that they stormed the Capitol, ransacked the halls of our highest offices, and carried out acts of hooliganism that killed five Americans and injured countless more.

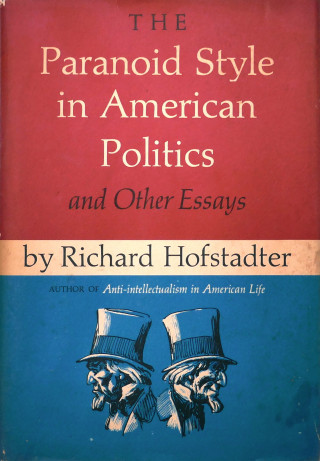

Richard Hofstadter, a midcentury American historian and public intellectual, gives us a place to start. In his “The Paranoid Style in American Politics” (1964) — the lead essay in a book by the same name — Hofstadter offered an early diagnosis of the type of conspiratorial politics that exploded on the steps of the United States Capitol. He called it a “paranoid style,” and in naming it, began the process of trying to understand it — of putting it under historical scrutiny and identifying its root causes and consequences. But to be clear, the paranoid part was not a clinical pathology. Rather, what mattered most was the style part. He likened it to something being described as “baroque” or “mannerist.” The paranoid style reflected a way of seeing and doing politics, which meant that it was capable of being studied and eventually understood.

Hofstadter felt compelled to write because he saw a version of the paranoid style rising in his own time; if January 6 has taught us anything, it’s that we are now living in the long arc of its creation.

¤

Hofstadter tells us that, at its core, the paranoid style uses conspiracy to engage in subversion. The political paranoiac can’t stomach society as it is and thus seeks to destroy it under the guise of some looming threat: a deep state, antifa, migrant caravans, transgender bathrooms, an international pedophile ring. Perceived persecution runs deep, and those taken with the paranoid style channel their victimhood by believing the world is one vast conspiracy. But here is the key idea: it is not just personal grievance. The paranoid style is the paranoid style because it manages to take victimhood and transmit those feelings of personal injury onto the nation’s fate. One person’s paranoia thus becomes an attack on a culture or a way of life, turning a lone loony into a proud member of a “silent majority” — a collective firewall against something that needs no firewall.