The second hour of “Gone with the Wind,” the bold, almost brazenly romantic Civil War epic that won ten Academy Awards, is largely a portrait of hell. “The skies rained death,” the screen reads. General William Tecumseh Sherman and his Union Army have brutally taken Atlanta during a hard-fought campaign, at a combined cost of nearly seventy-five thousand casualties. Scarlett O’Hara, a wealthy white Southerner, picks her way out of the city, passing the littered remains of wagons and men while vultures hover overhead. All the plantation houses she sees have been reduced to charred ruins.

Only her own plantation has survived Sherman’s assault. Scarlett opens the door to find her father, but it’s clear from his blank eyes that he’s a broken man. The house, too, is a mere shell of itself. The Yankees used it as a headquarters, and they stole everything they didn’t burn: livestock, clothes, rugs, even Scarlett’s mother’s rosaries. The slaves, too, are gone—only three out of a hundred are left. Scarlett, starving, staggers behind the house and tries to eat radishes from the ground, searching for whatever scraps of food remain.

This scene is typical of the way Sherman’s march through Georgia is usually depicted. In the fall of 1864, Sherman took sixty thousand Union soldiers some two hundred and fifty miles from Atlanta to the ocean, scorching a vast swath of the state along the way. Parts of Atlanta were razed to the ground, and Savannah became Sherman’s “Christmas gift” to Abraham Lincoln. The campaign is remembered as a path of destruction, a total war waged against the white civilians of the South.

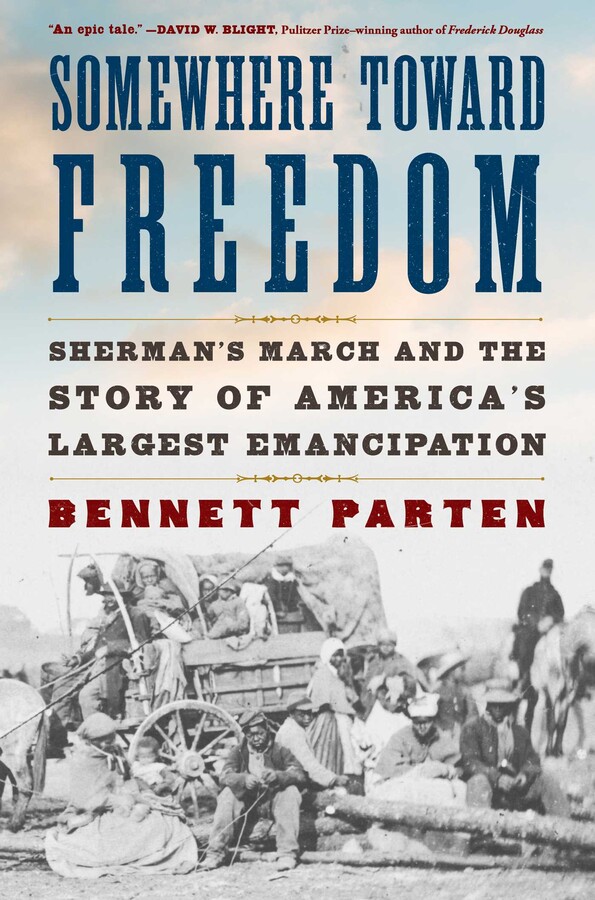

Yet to the many enslaved people across the state who left their homes and followed Sherman to the sea, the march meant freedom. Theirs was not the stately freedom of legislative proposals and Presidential proclamations, of men debating and signing documents. It was, instead, military emancipation—always a messy endeavor, full of risks and fears and betrayals, and one that is sometimes forgotten in accounts of how emancipation occurred. This is the central narrative of Bennett Parten’s new book, “Somewhere Toward Freedom.” Parts of this story have been told before, in bits and pieces, in broader works about the Civil War or emancipation or the march itself. But Parten’s may be the first to make freedpeople its sole focus, and to claim that they were essential to the march’s meaning.