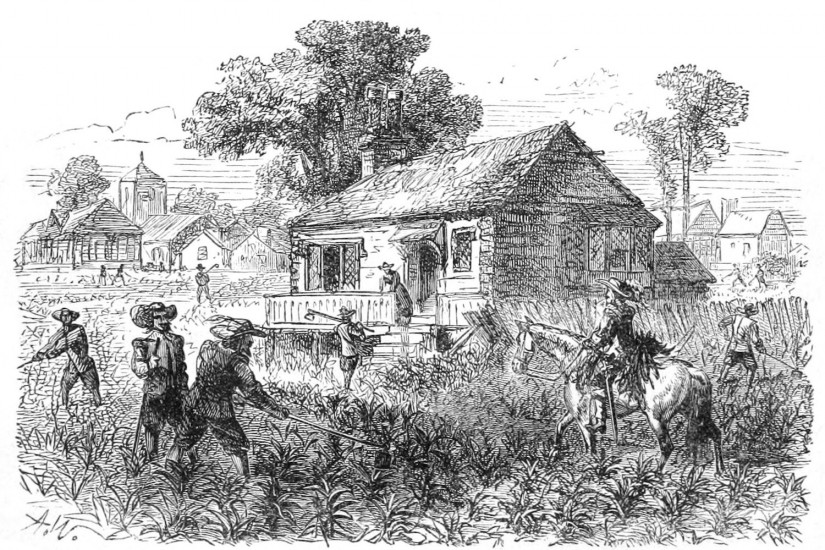

The Jamestown Project works best when Kupperman sets aside her special pleading for Jamestown as an inspirational success and as our singular national cradle. The book sparkles when she instead recovers the complex and cosmopolitan backdrop to English colonization. During the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, an ambitious mix of English visionaries and rogues probed the wider world for new opportunities. Mixing utopian dreams with pragmatic greed, they sought great fortune and new power for their small, poor, and beleaguered island kingdom. Protestants and nationalists, they sought to break out of encirclement by the overbearing power of Catholic Spain, which financed European domination with gold and silver extracted from Mexican and Peruvian mines. Seeking a share of this wealth, these Englishmen preyed upon Spanish ships and seaports, or they conquered and plundered the Catholic Irish. In stretching westward into North America, the English sought pirate bases to afflict the Spanish, and new plantations to exploit the Indians just as they had done to the Irish.

Kupperman also sheds light upon England’s growing engagement with the Muslim world as a mix of attraction and repulsion. Some of the Virginia Company’s leaders had cultivated trading partners and potential allies among the Muslim rulers of Morocco and the Ottoman Empire, while some English mercenaries (including Smith) fought against the Turks on behalf of Christian warlords in the Balkans. She suggests that familiarity with Islam facilitated colonial improvisation in the New World--but how she does not say. In sum, her English promoters and adventurers lived in a complex world of mixed and multiple dangers and opportunities which invited great gambles that could spin into madness, as they did at Jamestown.

By taking readers on a sprightly jaunt around the Mediterranean, into Ireland, and across the Atlantic to both the tropics and the Arctic, Kupperman reveals Jamestown as only one small, risky, and tenuous foray in a global array of English ventures, rather than the essential seed of a future superpower. But she also makes a good case that Jamestown’s founders deserve some credit for their unusual persistence through the initial decade of folly and suffering. Given the miserable failures of other English colonial ventures, most sensationally at Roanoke during the 1580s, she argues that Jamestown stands out for its founders’ surprising endurance.

If so, let us now praise infamous men: the long-maligned leaders of the Virginia Company in London. Distant, wealthy, and English, they make convenient foils in an enduring American populist story originally crafted by Smith. In this version, the corporate leaders were out-of-touch elitists, afflicting the poor colonists with unrealistic expectations and foolish instructions. Success allegedly came only when ordinary colonists defied their superiors by becoming pragmatic and resourceful Americans guided by experiment and experience.