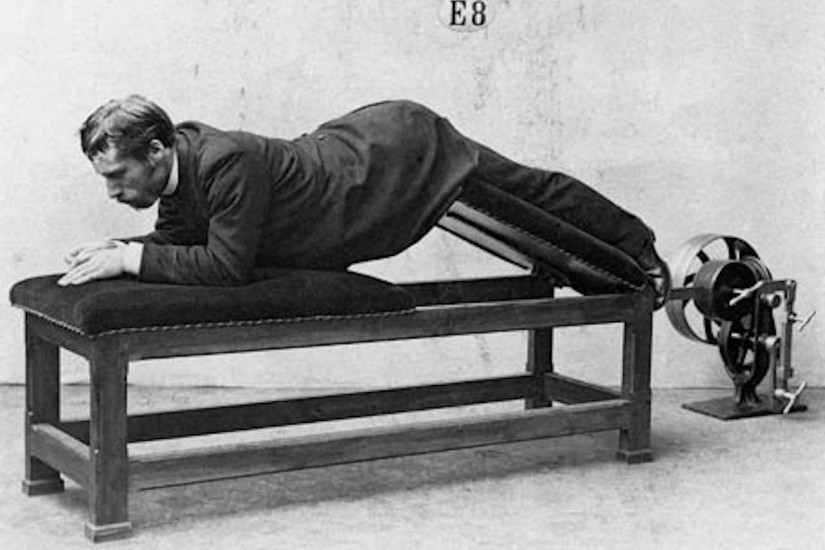

The Swedish physician Gustav Zander’s institute in Stockholm, founded in the late nineteenth century and stocked with twenty-seven of his custom-built machines, was the first "gym" in the sense that we know the word today. His mechanical horse was an early version of the Stairmaster, a contraption for cardiovascular fitness designed to imitate a "natural" activity. His stomach-punching apparatus evokes contemporary "ab-crunching" machines. What makes Zander so important, for anyone trying to trace the Cybex family tree, is what happened when his machines, created in a European cultural context, immigrated to the US in the early twentieth century. They are prototypes of the workout equipment now ubiquitous in American life.

In Stockholm, Zander’s institute primarily treated children and male workers. Supported by the state, it was equally accessible to those with and without means. The complex mechanized system was believed uniquely capable of correcting physical impairments brought about both by accidents of birth and by hard labor. A follower of Per Hendrik Ling’s movement cure, Zander argued that the key to health was not blood letting, purging, or strenuous acrobatics (other allopathic "cures" of the time). Instead, one needed to practice "progressive exertion," the controlled, systematic engagement of the body’s muscles in order to build strength.

In the US, however, Zander sought and found a very different clientele. His award at the 1876 Centennial and International Exposition in Philadelphia for best mechanical design provided a launching pad for marketing Zander machines as upscale devices for the rising American business class. His machines offered, Zander explained to an American audience, "a preventative against the evils engendered by a sedentary life and the seclusion of the office." In fact, Zander claimed, there was no treatment quite so appropriate for these emerging white-collar men (and their wives) as his mechanized system. While doctors’ pills and potions might be easier to procure and quicker to ingest, the "increased well-being and capacity for work" gained by those who used his machines, he argued, was "rich compensation for the time bestowed on them."