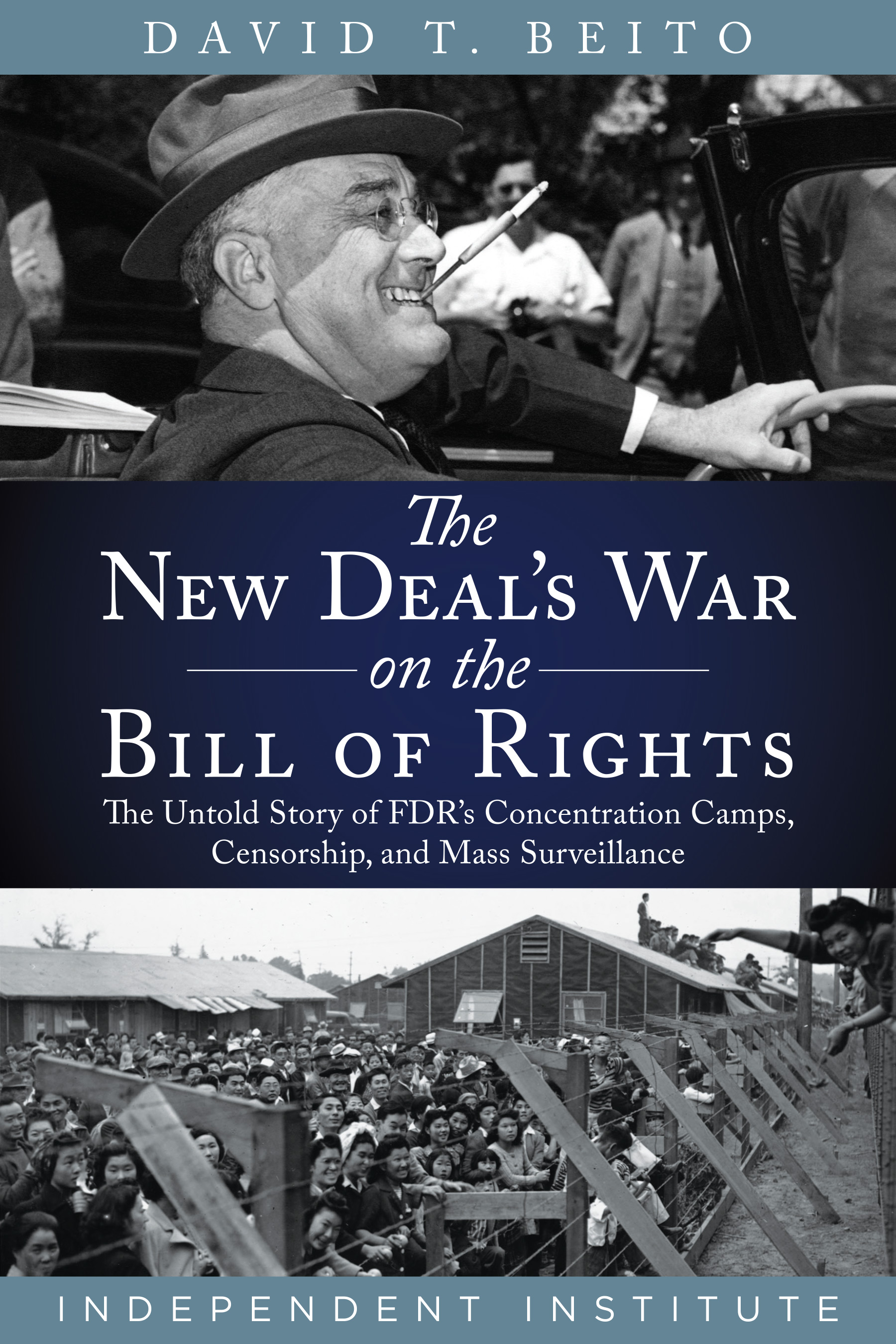

When I arrived at the University of Alabama almost a decade ago to begin graduate school and met the historian David Beito (who would become the co-advisor on my dissertation), he was just beginning a project on Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s disregard for Americans’ civil liberties. Most critics of FDR point to Executive Order 9066 which forced 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry into concentration camps—around two-thirds of which were in fact American citizens—as an anomaly of his otherwise solid record on civil liberties. In The New Deal’s War on the Bill of Rights, however, Beito goes beyond internment and challenges these notions. Through detailed archival research, he has penned one of the most damning scholarly histories of Roosevelt to date.

The Roosevelt consensus among historians, to the extent that it ever existed, has been unraveling for some time. Free market critics such as Robert Higgs, Burt Folsom, Jim Powell, Thomas Fleming, and Amity Shlaes have rightly condemned Roosevelt’s response to the Great Depression and his inclination to use the coercive power of the state to impose his policy prescriptions—often with undesirable results and unintended consequences. But there is also an emerging group of historians on the left—Richard Rothstein, Ira Katznelson, Linda Gordon, and Richard Reeves, among others—who criticize FDR for reinforcing the white male breadwinner home, for creating organizations such as the Federal Housing Administration that helped segregate America through redlining, for not supporting anti-lynching legislation, for not ensuring that the New Deal programs benefited minorities on a more equal basis, and for the internment of Japanese Americans. Even David Kennedy’s comprehensive history of the period is critical of Roosevelt on some margins.

Although some historians have criticized FDR, most of the historiography of Roosevelt gives him a pass on the abuse of civil liberties during his administrations and hails him as a champion of democracy often citing his soaring rhetoric and the Four Freedoms. In reality, as Beito demonstrates, Roosevelt’s liberalism did not lead him to care about Americans’ civil liberties and he violated the Bill of Rights time and time again while in office. Further, historians generally treat the internment of people of Japanese ancestry as an exception to Roosevelt’s solid record on civil rights and they generally excuse the president’s actions and cast blame on those who carried out the relocation and internment—such as General John L. Dewitt. Beito set out to prove that Roosevelt’s decision to intern Japanese Americans was consistent with his general disregard for the Bill of Rights.