Like many of the paintings I love, “Subway” teaches the viewer to see something special and valuable in the mundane. It’s a mildly subversive piece: We’re being invited to stare at people on the subway! Meanwhile, the subjects of the painting must stick to approved subway behaviors: furtive glances, quiet moments with friends or lovers, and above all the sustained performance of inattention to one’s neighbors.

“Subway” also wants to teach how to better see the USA. It presents an integrated whole and treats this crowd with the dignity afforded white, native-born men at the time. The painting’s central subjects are, to my eye, from left to right, a young woman applying lipstick, a dapper African American man who wears cool socks, a musician who for some reason I think is meant to be an immigrant from southern or eastern Europe^, a worker in a blue shirt (possibly Japanese), and a white woman in a compelling two-toned green dress. Lily Furedi instructs us in seeing the nation represented by an A train car.

(^in support of that hunch: according to Wikipedia, Furedi’s Hungarian father was a cellist…)

Born in Budapest in 1896, Furedi lived in uptown Manhattan, far uptown, past Harlem, in Washington Heights at 719 West 180th near the just-opened George Washington Bridge (and near the coffee shopwhere I’m composing this post). She painted “Subway” in 1934 as part of the “Public Works of Art Project,” a federally funded relief program for artists that employed 2,500 artists and sponsored over 15,000 works of art in just one year—it was a cousin to the more famous Federal Writer’s Project of the WPA (Works Progress Administration) that employed soon-to-be luminaries like Zora Neale Hurston and Richard Wright. They were hired to prepare an extensive series of guides to American places. Like Furedi’s painting, they too evidenced a commitment to providing an alternative to nativist and racist nationalisms that had just a decade before inspired immigration restriction and allowed the Ku Klux Klan a seat in the inner circles of the Democratic Party.

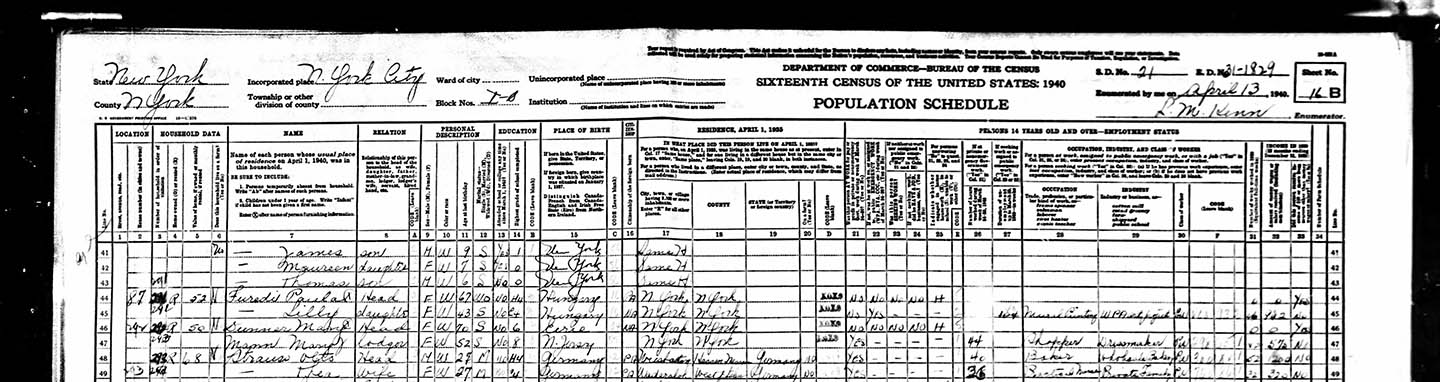

Furedi became the subject of a very different sort of project to depict America on 13 April 1940, when Lucile M. Kenn knocked on the door of Furedi’s apartment. Paula Furedi, Lily’s mother, probably invited Kenn in and asked her to take a seat. Kenn drew out a large leather portfolio containing her census forms. On side B of sheet 16, Kenn recorded the summary details of the two Furedis’s lives.