With the 2018 midterm elections approaching, the role of money in politics once again looms large in American political discourse. For many, shadowy super PACs, mega-donors, and dark money stand in stark contrast to the sanctity of the individual voter. Political actors recognize and deploy this, with politicians going to great lengths to avoid seeming beholden to monied interests. This, however, is not a new issue in American politics. Fears of wealth’s influence resonated in the nineteenth century as well, as electoral combatants used accusations of purchased influence to attack their opponents’ legitimacy. Even as the Civil War loomed, such rhetoric helped shape the terms of debates over the Union’s future. We see this with particular clarity in Virginia, as Virginians wrestled with secession during the secession winter. Much as opponents of slavery had long accused the “Slave Power” of wielding undemocratic political influence, those combating secession summoned fears of slave money (particularly that spent in the political arena by slave traders) to undercut disunion’s democratic legitimacy and to bolster the Union.

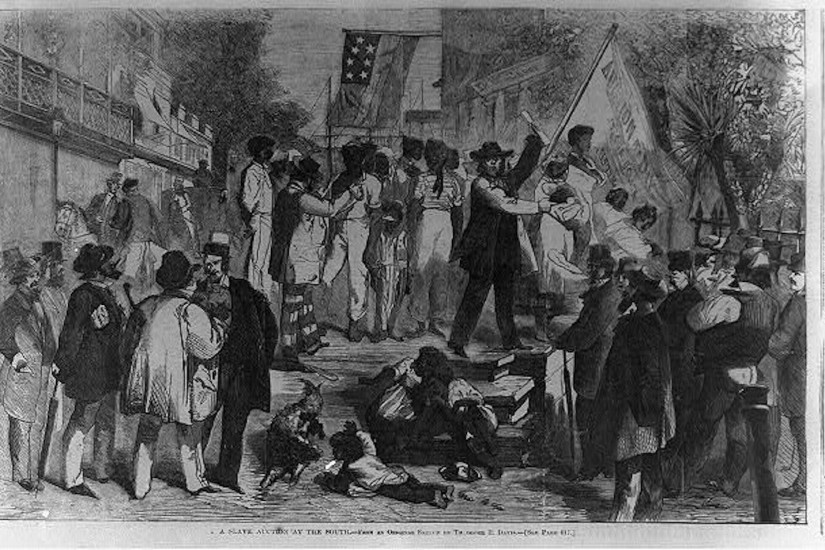

Slave traders and their political influence had long been an obvious rhetorical target. As the most obviously odious of all the actors within the slave system, they could be (and were) attacked with particular venom. And connection to them and their ill-gotten gains could prove damning. In 1844, Horace Greeley blamed slave traders for Martin Van Buren’s defeat in that year’s Democratic Convention, citing their desire to see Texas annexed in order to increase the prices of the enslaved, while in the 1850s a Stephen Douglas mouthpiece attacked a rival as the “the nigger traders’ candidate for President” for opposing homestead legislation. Linkages to slave commerce—and to the money generated therefrom—was a potent rhetorical tool in the parlance of the antebellum United States.

In 1860 and 1861, as state conventions assembled to debate secession, the possibility that slave traders’ lucre might influence the course of gained heightened significance. Such fears had considerable credibility even within slave states where Unionist delegates hailing from regions with lower enslaved populations clashed with their counterparts from the plantation belts.