The American mall has supposedly been dying for years. The Guardian announced its death in 2014, in an article featuring Seph Lawless’s photography of abandoned malls, their once-lively atriums gone to seed. In 2015, The New York Times published its own photography of eerily empty buildings in Ohio and Maryland. Then came a string of stories in 2017 and 2018, when Time, The Wall Street Journal, and CNN declared the end of the mall anew, all citing a Credit Suisse report anticipating that about one in four would close by 2022.

The cause of death was variously chalked up to the growth of e-commerce, the demise of the department store, and the fact that our country has been overmalled since the 1990s, when developers saturated the suburbs, building new shopping meccas just miles from old ones. Since the coronavirus pandemic hit, the forecasts have grown only more dire: In June 2020, a former department-store executive predicted that a third of malls would close by the next year.

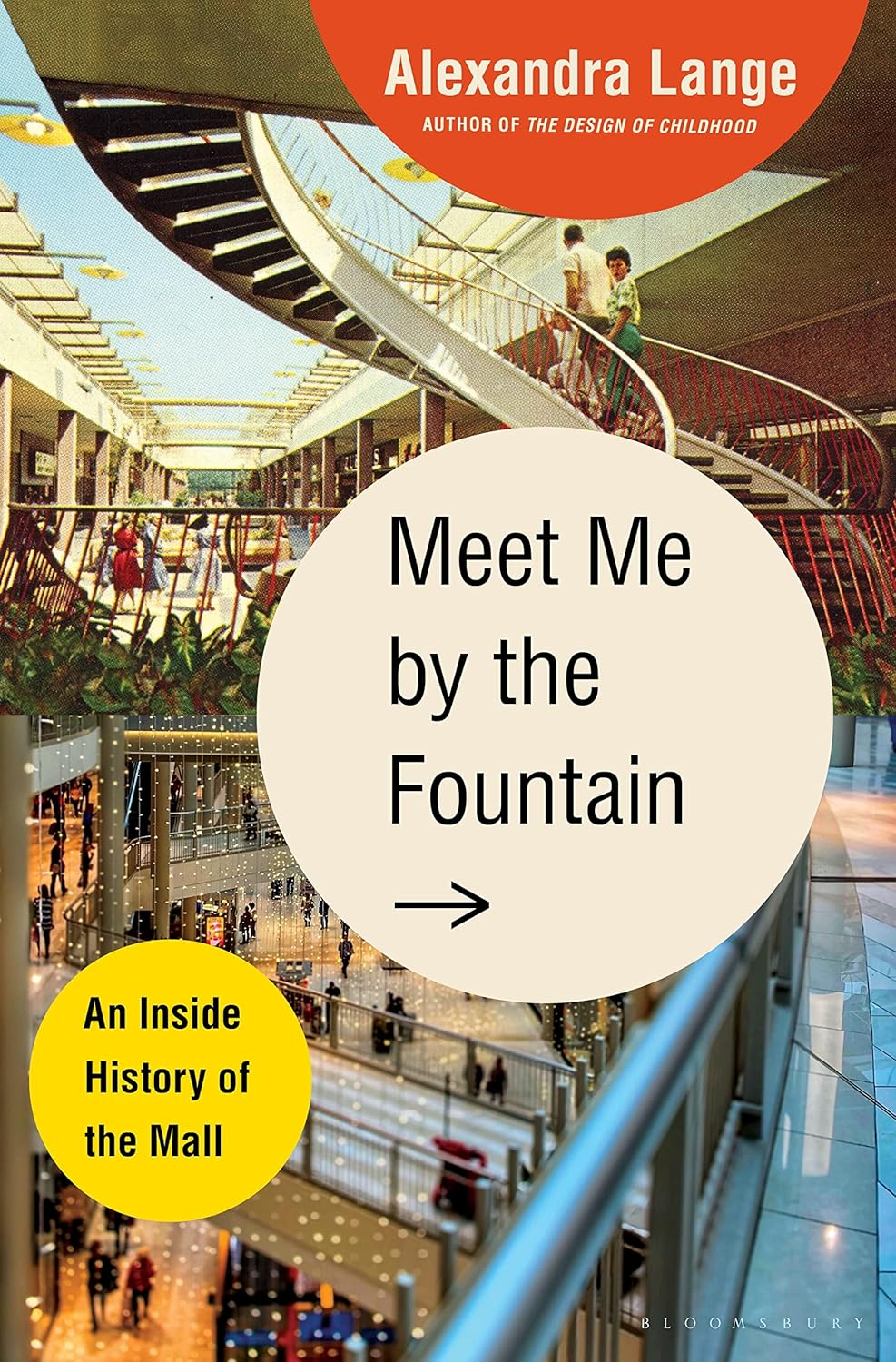

As the design critic Alexandra Lange writes in her consummate study Meet Me by the Fountain: An Inside History of the Mall, “Malls have been dying for the past forty years. Every decade rewrites the obituary in its own terms.” Lange considers how, since the 1978 movie Dawn of the Dead, we have been using “the apocalyptic scale, the language and imagery of civilizational collapse,” to describe the state of this most American form of architecture. “And yet,” she writes, “the majority of malls survive. And yet, people keep shopping.” (A 2021 study found that as of June of last year, the number of mall visitors across the country was actually 5 percent higher than before the pandemic.)

Meet Me by the Fountain challenges the dominant narrative. Lange wants us to consider how in prematurely writing off the mall as dead, or in thinking of it as “a little bit embarrassing as the object of serious study, ” we neglect the important role these buildings have played in our lives. At their best, malls have always been more than just sites of conspicuous consumption and leisure, but places for communities to gather, to see and be seen, fulfilling a “basic human need.” Lange’s book reminds us that the mall has helped shape American society, and has evolved with our country since the 1950s. And she posits that there’s still a place for malls in our society, as long as they adapt to better serve their communities.