Sonny Rollins is the last living progenitor of jazz’s make-it-new ascent during the 20th century. Like many of his peers, Rollins has at various times been both inside and outside of history’s flow; he has also been at various times an enigma and a victim, a cautionary tale and—now more than ever—a role model. Though sidelined by illness, Rollins, now approaching his 93rd birthday, remains a living testament to jazz, to American music, and to improvisational possibility itself. He has never quite enjoyed the same instant-recognition status in popular culture as Sinatra, Aretha, or even his onetime bandmate Miles Davis. But he’s also more than a cult hero revered by those huddled along the fringes of the musical zeitgeist. Rollins has always shown an iron will that permits him not just to invent and reshape sound but also to adapt to and, above all, survive whatever the world has thrown at him.

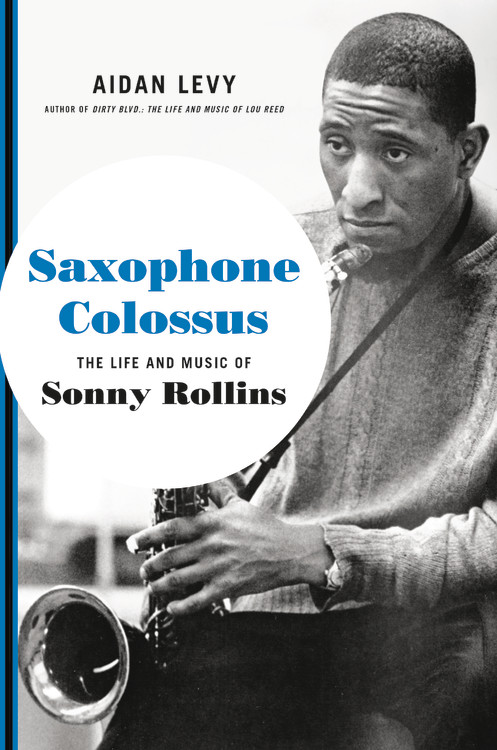

A figure of such heroic stature deserves a monument worthy of him. And until something even larger and more expansive comes along, Aidan Levy’s new biography of Rollins, Saxophone Colossus, will do nicely. Taking its name from the 1957 album that I, among many others, would recommend as the best place to begin assessing Rollins’s storied, varied, and endlessly fascinating body of work, Saxophone Colossus can be read as a bildungsroman of a Black American artist reinventing himself and his art throughout a crowded, challenging life. With meticulous detail (the reference notes and annotations are almost as voluminous as the footnotes to a David Foster Wallace article about a tennis match), Levy’s book recounts Rollins’s painstaking, dogged, and ultimately inspirational struggle to summon forth the sounds he heard and continues to hear in his head. To do so, if I’ve properly read what both Levy and Rollins say about this process, you need to take in whatever’s in the air around you, rechannel the raw data, and make it up—and make it new—as you go along. You have to, in other words, improvise. As Rollins puts it early in the book, it’s about “having my rudiments ready to go whenever the spirit hits me. My part of the bargain. I want to get that right…it just has to happen because that’s what jazz is. It’s natural. It’s like the sky—it’s never the same two days in a row.”

To be able to make creativity and invention sound “natural,” one needs an avid, almost greedy urge to absorb anything—and everything—that is out there. Accounting for Rollins’s eclectic range of interests is part of what gives Levy’s narrative the worlds-within-worlds momentum of a Rollins solo.