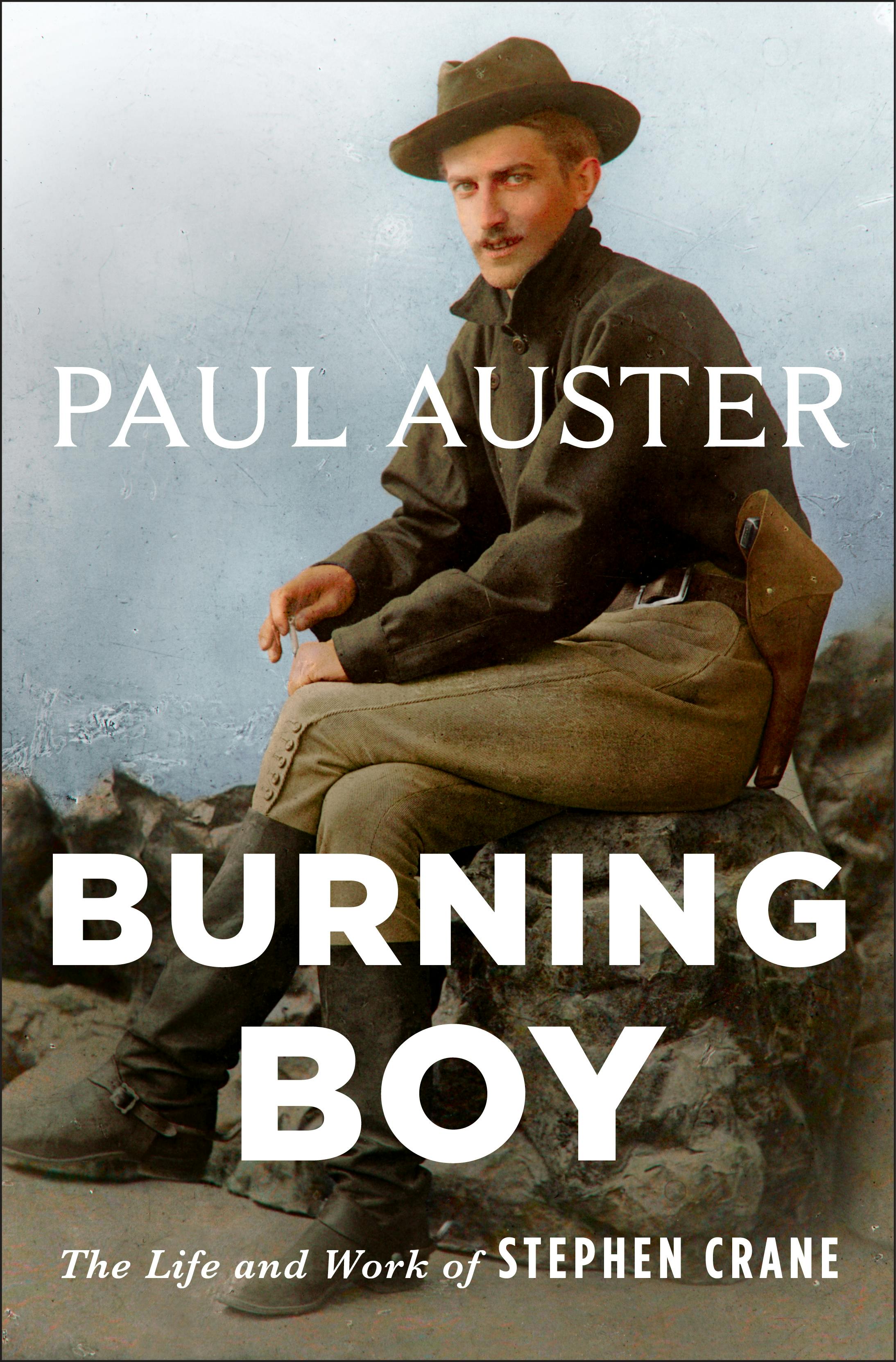

Paul Auster’s “Burning Boy: The Life and Work of Stephen Crane” (Holt) is a labor of love of a kind rare in contemporary letters. A detailed, nearly eight-hundred-page account of the brief life of the author of “The Red Badge of Courage” and “The Blue Hotel,” augmented by readings of his work, and a compendium of contemporary reactions to it, it seems motivated purely by a devotion to Crane’s writing. Usually, when a well-established writer turns to an earlier, overlooked exemplar, there is an element of self-approval through implied genealogy: “Meet the parents!” is what the writer is really saying. And so we get John Updike on William Dean Howells, extolling the virtues of charm and middle-range realism, or Gore Vidal on H. L. Mencken, praising an inheritance of bile alleviated by humor. Indeed, Crane got this kind of homage in a brief critical life from the poet John Berryman in the nineteen-fifties, a heavily Freudian interpretation in which Berryman was obviously identifying a precedent for his own cryptic American poetic vernacular in Crane’s verse collections “The Black Riders” and “War Is Kind.”

But Auster, voluminous in output and long-breathed in his sentences, would seem to have little in common with the terse, hard-bitten Crane. A postmodern luxuriance of reference and a plurality of literary manners is central to Auster’s own writing; in this book, the opening pages alone offer a list of some seventy-five inventions of Crane’s time. The quotations from Crane’s harsh, haiku-like poems spit out from Auster’s gently loquacious pages in unmissable disjunction. No, Auster plainly loves Crane—and wants the reader to—for Crane’s own far-from-sweet sake.

And Auster is right: Crane counts. Everything that appeared innovative in writing which came out a generation later is present in his “Maggie: A Girl of the Streets” (1893) and “The Red Badge of Courage” (1895). The tone of taciturn minimalism that Hemingway seemed to discover only after the Great War—with its roots in newspaper reporting, its deliberate amputation of overt editorializing, its belief that sensual detail is itself sufficient to make all the moral points worth making—is fully achieved in Crane’s work. So is the embrace of an unembarrassed sexual realism in “Maggie,” which preceded Dreiser’s “Sister Carrie” by almost a decade.

How did he get to be so good so young? Crane was born in Newark in 1871, the fourteenth child of a Methodist minister and his politically minded, temperance-crusader wife. Early in the book, Auster provides, alongside those inventions, a roll call of American sins from the period of Crane’s youth: Wounded Knee, the demise of Reconstruction, and so on—all of which, however grievous, happened far from the Crane habitat. The book comes fully to life when it evokes the fabric of the Crane family in New Jersey. The family was intimately entangled in the great and liberating crusade for women’s suffrage, which was also tied to the notably misguided crusade for prohibition. Crane lived in a world of brutal poverty—and also one of expanded cultural possibilities that made possible his avant-garde practice, and his moral realism.