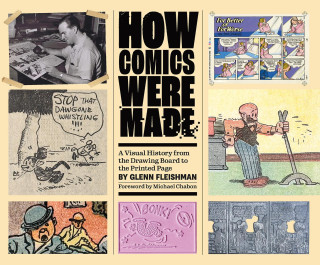

I have personal reasons, therefore, to be grateful to Fleishman and How Comics Were Made, his deeply researched and splendidly designed new history of that great American art form, the newspaper comic strip. Unlike previous historians of the form, who have tended to concentrate on its social, political, cultural, and artistic aspects, Fleishman considers its inception and development over the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries as a product of rapid innovation and change in the technologies of printing, in particular of mechanical image reproduction, and his book is therefore, necessarily, a history of mechanized printing itself. It’s the history of the mass industrialization of printing over that period, of how that process gave rise to the modern newspaper and the numerous crafts and specializations—all of which required skill if not outright artistry—that rapid technological development, driven by fierce competition for vast readerships, demanded. But it’s also, accidentally, a history of my grandfather.

Irving L. Chabon (1900–1974) was, as far as I know, primarily a typesetter; but even if he never worked directly in comic strip production, deploying one of the many surprisingly baroque, no doubt tedious processes expounded by Fleishman with such affection and verve, the world limned here—a world of weird alchemies of acid and metal and light, of intimate bullpens where talented colorists and gamboge adepts wielded fine brushes and X-Acto knives, of block-long plants that roared night and day rolling a thousand Möbius miles of newsprint through the works, of Ben Day, Craftint, Zip-A-Tone, and flongs—was my grandfather’s world. Reading How Comics Were Made, the fruit of long devotion, insightful scholarship, and dogged sleuthing, vividly restored that world and that history to me, half a century after my grandfather’s death and a century, more or less, since his taking up the printer’s trade.

My personal loss—the loss of a strand of family history—and its partial, bright recovery in How Comics Were Made merely reflects in miniature the far more severe loss that Fleishman has so resolutely staved off for all of us. He gives a good, illuminating account of the state of comic strip production in the post-newsprint age. But his title acknowledges the poignant, past-tense truth of the newspaper strip, an American art form that began as an experiment in raucous urban satire; ascended swiftly to technical and artistic brilliance and a kind of mass narrative dominance that both presaged and, for a long time, rivaled radio and Hollywood for what would later be called market saturation; then entered a second period of creative experimentation that (in hindsight) reached its peak with Calvin and Hobbes—only to die suddenly, with the death of the physical newspaper, almost exactly a century after its birth.