In signing the Declaration of Independence in 1776, Benjamin Franklin is reputed to have quipped to fellow signer John Hancock that “we must indeed all hang together or we shall assuredly hang separately.” Whether or not he actually said this about his own neck and the noose that awaited all traitors if caught by His Majesty’s government, Franklin had long insisted that the colonies had to hang together or die.

He first made the point in the mid-1750s in reference to a looming trans-Appalachian military threat to the British Empire posed by backcountry French Canadians and their Native allies. In a drawing that in effect invented political cartoons worldwide, Franklin insisted that the British American colonies must hang together, indivisibly. The cartoon repeatedly resurfaced in the 1760s and 1770s, but these revivals came with a dramatic serpentine twist: after 1763 the main threat to America was no longer French or Indian but British.

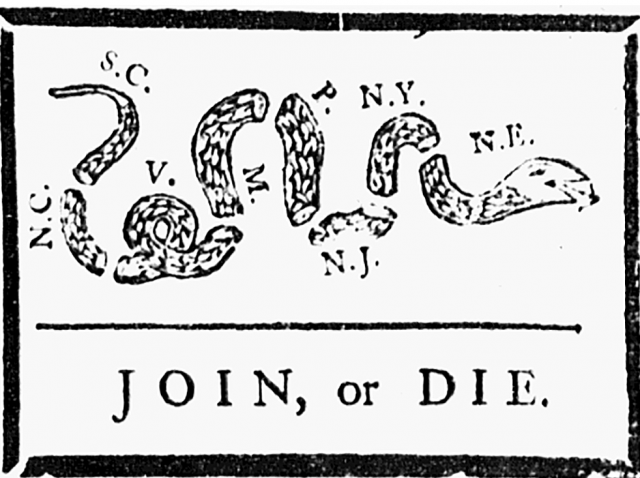

Franklin’s cartoon initially appeared in his own newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette, on May 9, 1754, sandwiched between two short and interrelated articles. The first told readers of a dashing young Virginia officer’s mission to inform French agents infiltrating western Virginia and Pennsylvania that these lands belonged to His Majesty George II. (The officer was named George Washington.) The French aimed to control the Forks of the Ohio (modern-day Pittsburgh), with the help of allied Indians. The “disunited” condition of the various distinct British colonies, argued the article, gave the French “the very great advantage of being under one direction, with one council, and one purse.” The second piece discussed an upcoming intercolonial conclave—today known as the Albany Congress—that would aim to coordinate British American resistance to these French encroachments. In between these two brief articles lay the illustration of a sinuous snake divided into eight sections.

Each section was labeled with initials, making clear that the snake represented the mainland British colonies from New England (“N.E.”) to the Carolinas, North and South (“N.C.” and “S.C.”), connected by New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia (“N.Y.,” “N.J.,” “P.,” “M.,” and “V.”). These contiguous colonies, the cartoon argued, would survive only if they held together. Franklin here offered a clear message and a catchy slogan—“JOIN, or DIE”—well adapted to the democratic culture aborning in midcentury Philadelphia.

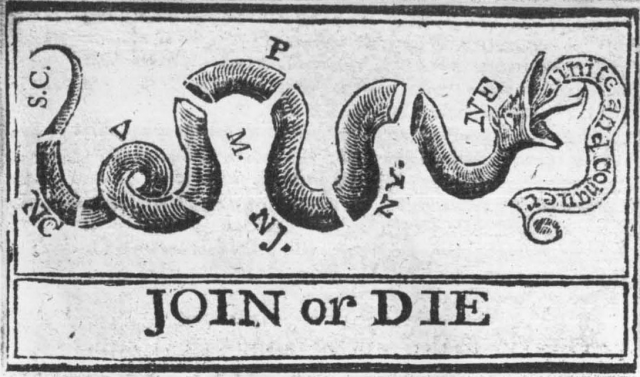

The simple image was easy to imitate precisely because it was not high art. On May 13, only four days after the birth of Franklin’s snake, it was reborn in Manhattan, when the New-York Mercury reprinted Franklin’s two essays and its own version of the cartoon.

New-York Mercury drawing, May 13, 1754. America’s Historical Newspapers.

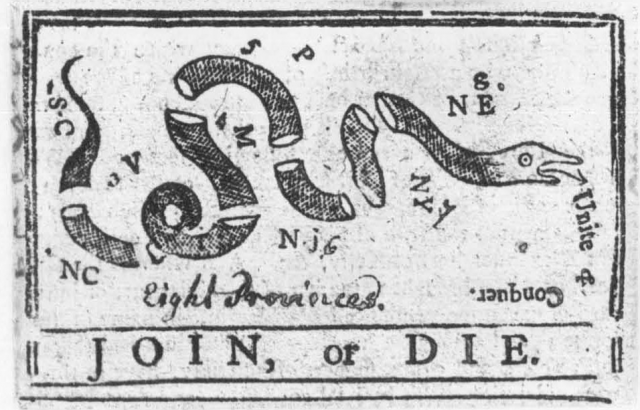

On May 21 the snake found yet another nesting place and also found its voice—this time in New England, as the Boston Gazette reprinted Franklin’s essays-and-image sandwich with yet another variant of the cartoon. Not to be outdone, the Boston News-Letter on May 23 served up its own variation, featuring a rather more anxious, round-eyed snake. In both graphics, the snake urged colonists to “unite and conquer.”

Boston Gazette drawing, May 21, 1754. Massachusetts Historical Society and Colonial Society of Massachusetts.

Boston News-Letter drawing, May 23, 1754. Boston Athenaeum and Colonial Society of Massachusetts.

Over the next two decades, Franklin’s snake would experience repeated rebirths. As the serpent’s popularity grew, the fact that its toothed end faced east, toward London, and not west, toward the French and Indian backcountry, would take on a significance that the initially Anglophilic Franklin had not originally intended.