To read Frost is to wonder which parts of a poem to take seriously—and to sense his presence over your shoulder, laughing at your mistakes. “I like to fool . . . to be mischievous,” he told the critic Richard Poirier in an interview, in 1960, for The Paris Review. One could, he suggested, “unsay everything I said, nearly.” By his own account, he operated by “suggestiveness and double entendre and hinting”; he never said anything outright, and, if he seemed to, then suspicion was warranted. In both his poetry and his personal life, Frost was a trickster, saying one thing and almost always meaning another, and perhaps another still. He was like the playful boy described in the lovely poem “Birches” (1915), bending tree branches beyond recognition, then letting them snap back to their natural state, all for his own amusement. As readers of his poetry, we’re just along for the ride.

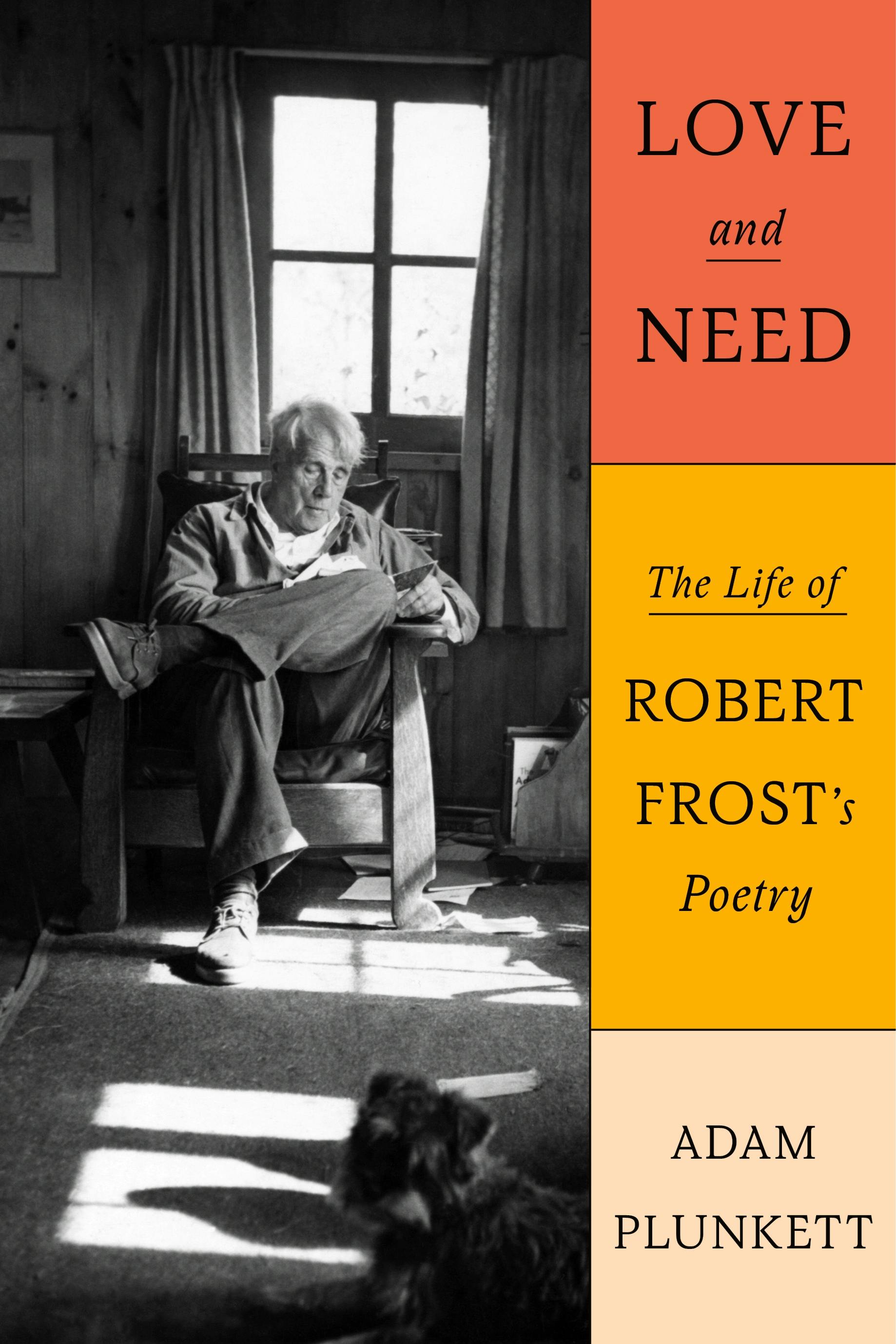

The critic Adam Plunkett expertly teases out the many meanings of Frost’s poems in “Love and Need: The Life of Robert Frost’s Poetry” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux). Blending biography and criticism, Plunkett shows how the circumstances of Frost’s peripatetic life gave rise to some of his most successful poems. As in the best critical biographies, Plunkett does not merely track down real-world inspiration for a given work. Rather, he brings together Frost’s personal life, literary sources, and publication history to enrich our understanding of the poems, then uses the poems to enhance our understanding of the life. The result is a thorough, elegant, and, at times, surprising study of Frost, who emerges as a remarkably complex poet and a compelling but complicated man.

Plunkett is not the first critic to trouble the popular conception of Frost as a wise woodsman dispensing comfort and inspiration. Astute readers have been challenging the naïve interpretation of Frost’s work for decades. The effort could be said to have started with Lionel Trilling, who, at a party for Frost’s eighty-fifth birthday, declared the guest of honor to be “anything but” a writer who “reassures us by affirmation of old virtues, simplicities, pieties and ways of feeling.” Frost was, rather, “a terrifying poet” and “a tragic poet.” (Frost, listening in the audience, appeared nonplussed.) Trilling was channelling the poet and critic Randall Jarrell, who, for years, had urged readers to turn away from Frost’s sentimental poems and consult instead the writer’s darker, spikier efforts, such as “Provide, Provide,” a sardonic paean to success, and “Acquainted with the Night,” as lonely a poem as there ever was.