As exclusion laws intensified during the late nineteenth century, Chinese migrants adopted increasingly sophisticated strategies to circumvent them. One ingenious technique involved forged identity papers that claimed that such migrants were the children of Chinese American citizens, and therefore eligible for citizenship. Men who immigrated this way were known as “paper sons”—sons in writing rather than in blood. Some papers were passed along by Chinese American citizens to members of their extended families back in China. Many were purchased through brokers who bought identity papers and resold them at a much higher price. Given the clandestine nature of the process, the true number of fictitious sons who arrived during exclusion will never be known. It is estimated that, by the mid-twentieth century, at least a quarter of Chinese people in the U.S. had entered the country using false papers.

One such person was the father of the writer Fae Myenne Ng. As a teen-ager, Ng’s father left China as Ng Gim Yim. He arrived at San Francisco’s Angel Island as You Thin Toy, in 1940, during its final year as an immigration-detention center. Like many who had come to the island before him, Ng’s father waited more than a month to be interrogated by an official, and was denied entry to the country on his first attempt, when his answers to his immigration interview were deemed incorrect. He was held on the island until his sister managed to hire an immigration lawyer.

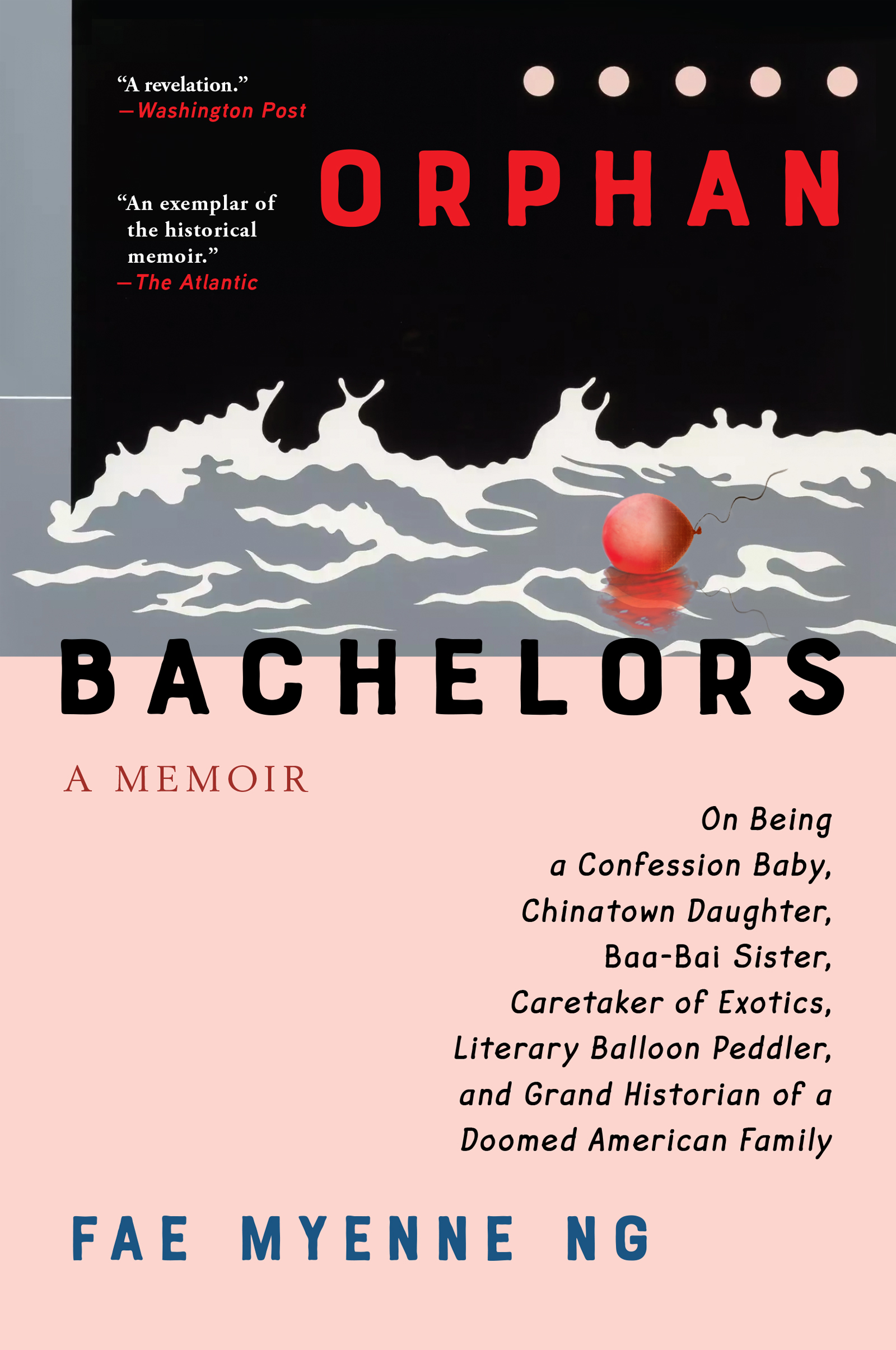

Ng tells the story of her father’s crossing in her memoir, “Orphan Bachelors,” a title drawn from her father’s term for Chinese men who came to the U.S. during the age of exclusion. His phrase underscores the heightened loneliness of these figures, who were effectively abandoned twice over—severed from their families back in China and unable to start their own in the United States.

Upon arriving in San Francisco, Ng’s father “had a bachelor’s life, living in a room at Waverly Place, having breakfast at Uncle’s Café, selling the Chinese Times at the Square, working those first few years in restaurants in Chinatown,” she writes. Despite living among bachelor men, he’s saved from their fate by Ng’s mother, whom he marries in 1948. Though their union is more the product of passivity than of love (“He didn’t say no, and she didn’t say yes, and this would become the family template, indirectness”), Ng, the first of their four children, is born eight years later.