Officially, Mayor Adams remains committed to the city’s plan to close Rikers and to open new high-rise jails in each of the boroughs (except Staten Island). Actually, his policies and budget will continue to put people there. “I have stated that I believe we need to close Rikers Island,” he said last year. “But while we are closing Rikers Island, you can’t have a facility where the gates and doors don’t work.” In other words: we can close Rikers, but first we have to fix it—namely, by reinvesting in its infrastructure and hiring more guards.

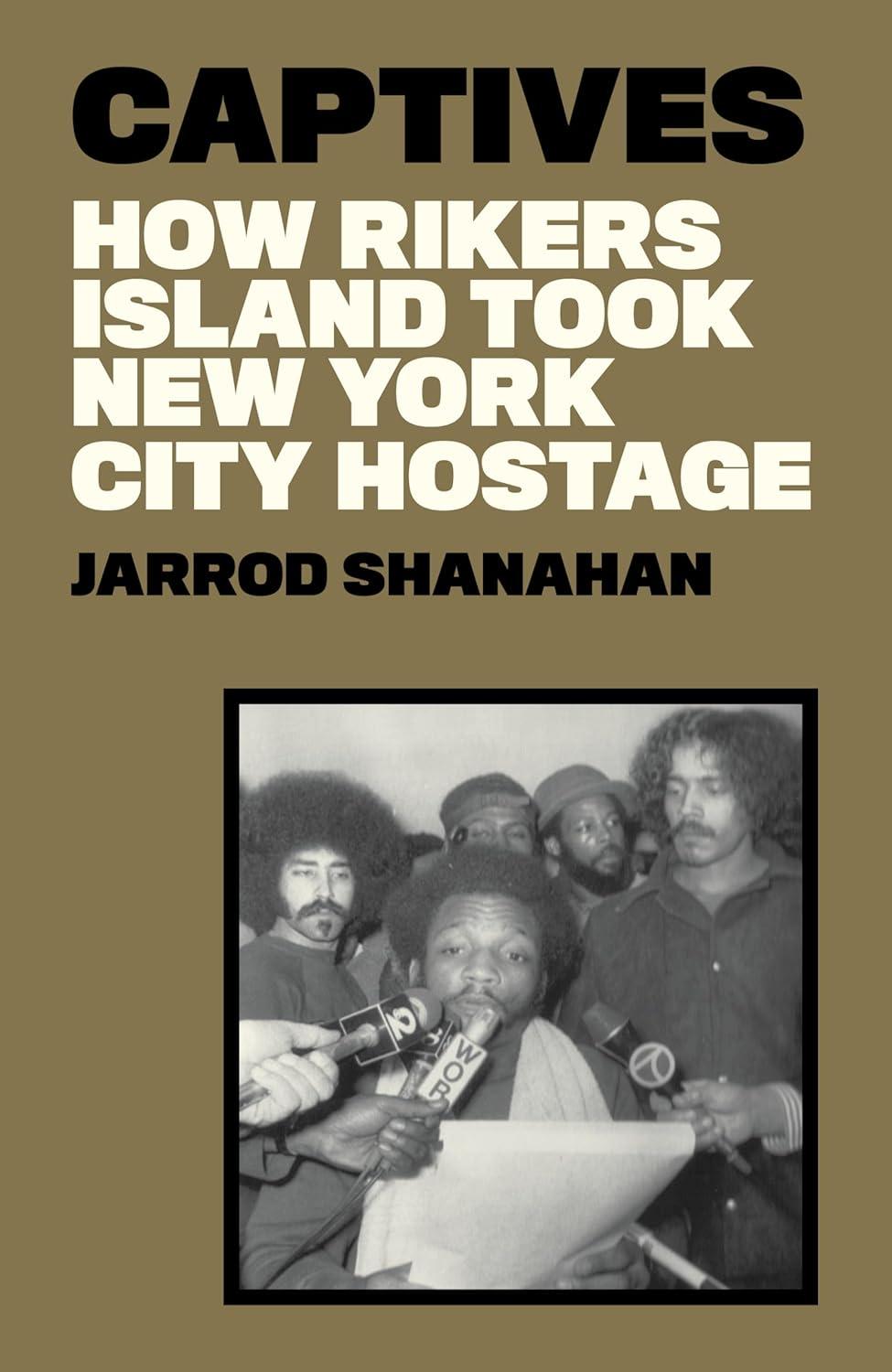

This precise dynamic has animated struggles within and over Rikers Island for nearly a century, as Jarrod Shanahan traces in his new book Captives: How Rikers Island Took New York City Hostage. Adapted from his doctoral dissertation at the CUNY Graduate Center, Shanahan’s Captives identifies Rikers Island as the black hole at the heart of the city, something like Times Square’s “necessary opposite,” summoned up out of the muck and mire of the East River: “at the same time that Rikers is removed from the city, a space of enforced isolation surrounded by the East River, it is also thoroughly constituted by New York City, and, in turn, constitutes it.”

Shanahan, who was arrested and held on Rikers during the anti-police rebellion that followed Michael Brown’s killing in 2014, tells the story of how the island, once imagined as a space of reform and rehabilitation, came instead to be “the domain of a violent custodial force that demanded—and won—almost-untrammeled recognition of their freedom to dispose of the city’s prisoners however they saw fit.” Abolitionists and other radicals opening this book might expect a history of prisoner rebellions and revolts, and these stories are present. But for Shanahan, the key antagonism in the city’s jails has in fact been that between guards and management. Captives is, in effect, a labor history: a history of guards in New York City’s jails generally, and on Rikers specifically, struggling for autonomy over their workplace—which is to say, for the right to deal out violence with impunity—against the managers, politicians, and judges seeking to impose their own ideas about how the city’s carceral institutions ought to be run.

Perhaps none of those bosses was more important than Anna M. Kross, Correction commissioner from 1954 to 1966. She adamantly pursued a project of “penal welfarism” in the city’s jails, attempting to transform them from spaces of neglect and abandonment into facilities that could actually improve people’s lives. “The lock-’em-up-forget-about-’em policy of the past is over,” she declared in 1955. For penal welfarists like Kross, the problem was not necessarily that New York City was locking up more and more people, but rather that the city’s jails were becoming overcrowded. “The end result” of NYPD clearing the city’s streets in order to create the appearance of surface order, Kross recognized, would “be that we will need MORE police, MORE prosecutors, MORE courts, MORE judges, and bigger and stronger bastilles to hold our prisoners.”