The memorial to President Abraham Lincoln was a sight to behold. A gleaming white, pyramid-shaped structure that resembled a giant cake with eight layers rising high above the Mall. At the top stood a statue of the Great Emancipator himself.

That is what the Lincoln Memorial would look like if architect John Russell Pope’s proposal had been adopted in 1912. Just a year earlier, lawmakers authorized $2 million to build a memorial to Lincoln. They appointed a seven-member commission headed by President William Howard Taft to recommend the design, but the final decision was up to Congress. After further debate and construction delay, the memorial was dedicated 97 years ago this week.

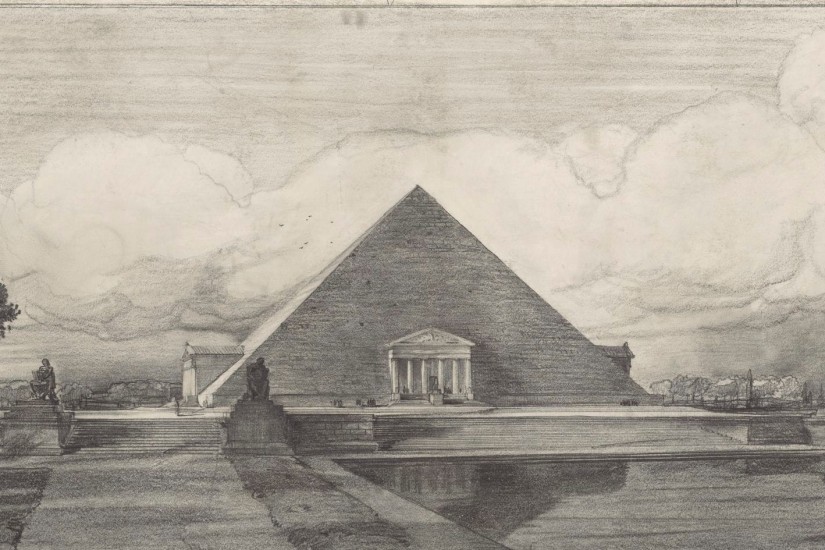

Pope’s pyramid scheme was one of several ideas he submitted in a competition with fellow New Yorker Henry Bacon. Pope’s terraced pyramid was styled after the ziggurat temple towers of ancient Mesopotamia, the “cradle of democracy.” The architect also suggested a four-sided, Egyptian-style pyramid, with portico entrances on each side.

The concept of an Egyptian pyramid wasn’t all that far-fetched. The neighboring Washington Monument, after all, is styled after an Egyptian obelisk.

Pope wasn’t the first to propose a pyramid for a national landmark. In 1800, Congress approved a plan by Benjamin Latrobe, the designer of the U.S. Capitol, to construct a pyramid with a floor 100 feet deep as a mausoleum for the remains of President George Washington. But the project was never funded. In 1837, architect Peter Force proposed to build the Washington Monument as a pyramid.

Pope’s ideas for a memorial to Lincoln weren’t as bizarre as one proposed in 1867 by Clark Mills, who designed the equestrian statue of Andrew Jackson in Lafayette Square across from the White House. Mills proposed to build next to the U.S. Capitol a 70-foot high bronze structure with no fewer than 36 separate figures, including six on horseback. Topping the memorial would be a statue of a seated Abraham Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation.