American schoolchildren still learn about Manifest Destiny, but few encounter the man who coined the term in 1845, the magazine editor John O’Sullivan. A Jacksonian associated with the Locofocos, the radical caucus within the Democratic Party, he was a friend of the trade unionists, anti-monopolists, and anti-capitalists of the era. O’Sullivan hailed from the democratic-republican tradition of Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine. He loathed the top-down arrangement of wage labor, despised the feudal inequalities of the money system, and welcomed westward expansion as an escape from the depredations of the factory and the city.

But the agrarian idyll of independent yeomanry, or what Jefferson called an Empire of Liberty, turned out more nightmare than dream. In practice, indigenous communities were exterminated or displaced. The slaveocracy gained ground territorially and ideologically, as the linkage between white freedom and nonwhite unfreedom tightened with the growing dependence of global profits on state-sanctioned bondage. And the brutalities of the capitalist machine, instead of being circumvented, intensified with the help of greater land and more labor to extract or exploit.

O’Sullivan’s journey from New York reformer to Mexican War booster to pro-Confederacy propagandist was not entirely unrepresentative. Many of the leaders of the workingmen’s movement in the 1830s and ’40s became apologists for slavery. Many others promoted the war with Mexico and the Indian Wars in general. And their ideological descendants can be spotted in future expansionist iterations, specifically among the anti-communist left, a sizable number of whom were driven to condone parallel cruelties, such as a strategic alliance with fascists in Latin America and an apartheid government in South Africa.

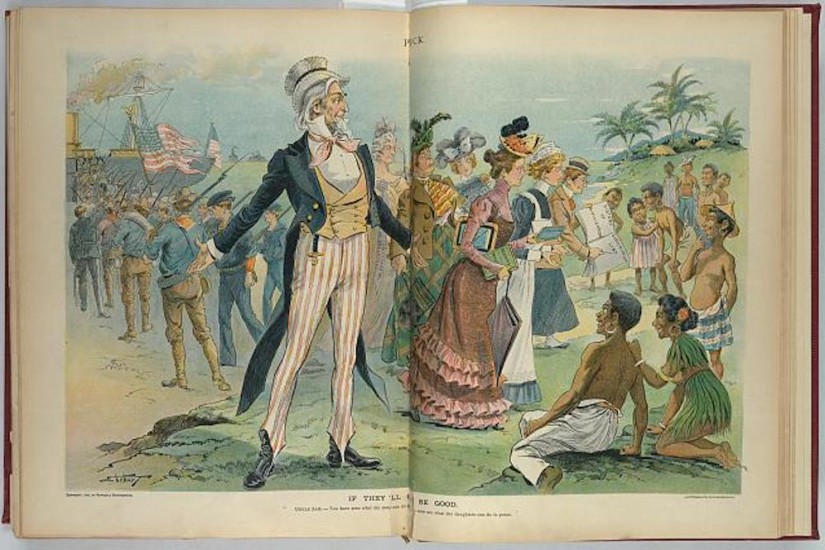

The Populists, who, in 1892, demanded such egalitarian reforms as an eight-hour workday and the end of private banking, backed the Spanish-American War six years later. They did so on anti-imperialist grounds, hoping to free Cuba from the grip of Spanish rule. But their presumption of goodwill on the part of the US government authorized, in the eyes of most Americans, the subsequent annexation of Hawaii, permanent control over Puerto Rico, a merciless slaughter in the Philippines, and a protectorate over Cuba with devastating long-term ramifications. Realizing their error, Populists became vociferous opponents of the latter developments, especially the bloodletting in the Philippines. But the damage had already been done, and many would take the same accommodationist path as onetime Populist presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, who once again made peace with imperial enterprises in Central America and the Caribbean.