The Pajaro Valley lies about 100 miles south of San Francisco. Its rich soil, abundant groundwater, and unusually long growing season make it one of the most productive agricultural regions in the United States. For years its main population center, the town of Watsonville, produced most of the frozen food on the nation’s dinner tables. Thanks to an insipid television commercial, millions of Americans in the 1950s knew it as “the Valley of the Jolly Green Giant.”

The Green Giant doesn’t live there anymore. He moved down to Mexico in the 1994, when Bill Clinton signed the North American Free Trade Agreement, and most of the domestic frozen food industry went with him. Watsonville no longer calls itself “the frozen food capital of the world.”

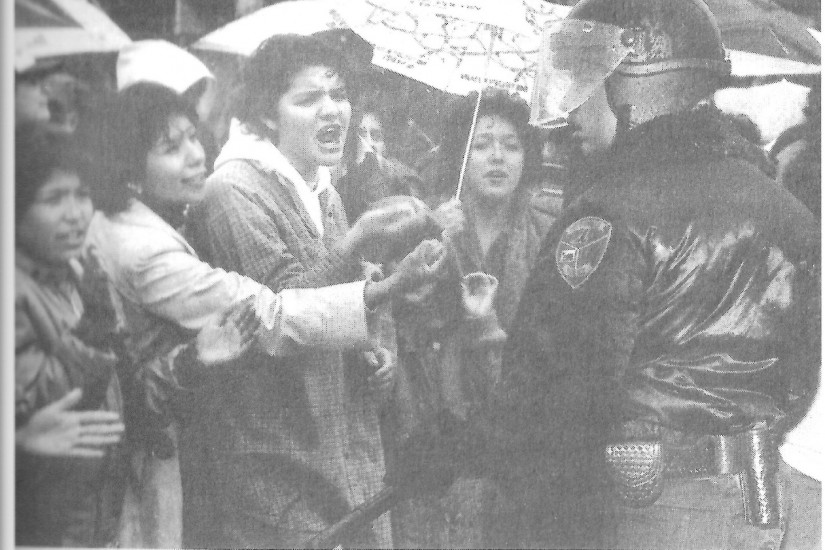

But in the mid-1980s, when the industry was still robust, 1,000 mainly Mexicana workers waged a successful 18-month strike against Watsonville Canning and Frozen Food, the town’s oldest and largest plant. In the face of the most difficult odds imaginable, they foiled a company effort to decertify their union, forced the plant owner to sell his business to avoid bankruptcy, and then won a contract from the new owner after a five-day wildcat.

Incredibly, this victory was achieved even though the union involved, Teamsters Local 912, had virtually stopped functioning when the strike began. This was September 1985, the height of the Reagan era, when private sector unionism was under a full-scale attack from which it has still not recovered. Across the country, workers with far more experience and resources at their disposal were suffering catastrophic defeats. Yet the Watsonville Canning strikers managed to prevail by maintaining a level of solidarity and self-organization that has few parallels in contemporary labor disputes. Over 18 long, difficult months, not one would break ranks and cross the picket line.

The strikers were ordinary people caught up in an extraordinary situation. Most were natives of Mexico, as many as 35 percent were undocumented, and nearly all were Spanish-speaking. 85 percent were women, many of them single mothers. Few had been active in the union, much less walked a picket line. The strike was a transformative experience for them.

Their triumph is a testament to the power of organization from below. But they did not do it alone. The paralysis of Local 912 at the outset of the strike left a void which many people tried to fill. In addition to the strikers themselves, forced by circumstance to assume new and unaccustomed responsibilities, these included union functionaries, union reformers, community activists, and self-conscious revolutionaries. Despite sometimes conflicting agendas, all contributed in one way or another to the final outcome. The strike itself became a laboratory for different styles of leadership.

Though the strikers welcomed outside help, they were steadfast in their insistence on making their own decisions and running their own strike. But they did not act in a vacuum, and the choices they made were influenced by the relationships they developed with others who brought their own ideas about how best to advance the struggle.