I have been through one war,” President William McKinley told a friend. “I have seen the dead piled up, and I do not want to see another.” Reluctant though he may have been to intervene in Cuban affairs, in the spring of 1898, barely a year into McKinley’s presidency, the United States did go to war with Spain, and American ships not only prowled the Caribbean but steamed into the Philippines’ Manila Bay, where Adm. George Dewey smashed the Spanish fleet. McKinley may have been unenthusiastic, but his young assistant secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt, was delighted. He’d been hoping for a war: “I think this country needs one,” he said. War builds character, Roosevelt thought, so he quickly finagled a military commission and raised a cavalry unit, famously called the “Rough Riders.” “Holy Godfrey, what fun!” Roosevelt exclaimed during the Battle of San Juan Hill.

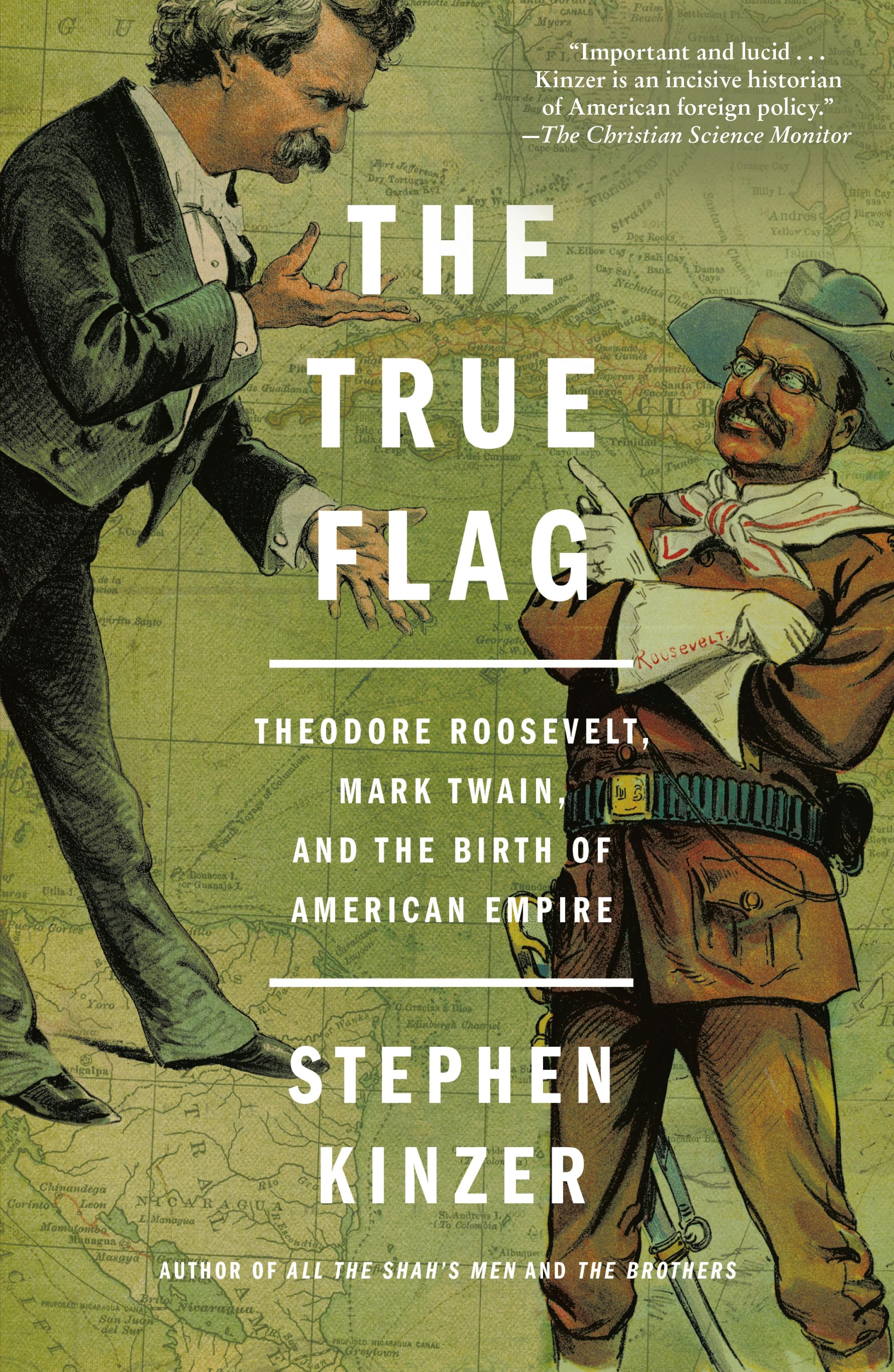

Although the story of the Spanish- American War has often been told, it just as often bears retelling, particularly when briskly chronicled by Stephen Kinzer, a former New York Times bureau chief in Nicaragua, Germany, and Turkey, and the author of books such as The Brothers: John Foster Dulles, Allen Dulles, and Their Secret World War and All the Shah’s Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror. In his latest book, The True Flag: Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain, and the Birth of American Empire, Kinzer recounts the foreign-policy debate that took place at the dawn of the 20th century. But this was no ordinary debate; it was about American military intervention in countries on their behalf or, more to the point, at their expense. Capturing an ambivalent approach to foreign policy that has persisted into our own day, Kinzer observes that the United States is a country of both imperialists and isolationists. “We want to guide the world,” Kinzer writes, “but we also believe every nation should guide itself.”

In the 1890s, however, the imperialists mostly ran the show. Chief among them was Henry Cabot Lodge, who served as a US senator from Massachusetts for 32 years, beginning in 1892. As the manufacturer Edward Atkinson describes it, Lodge was “the Mephistopheles” who whispered in Roosevelt’s ear (not that the Hero of San Juan Hill wasn’t capable of a jolly belligerence on his own). A Harvard graduate proudly descended from Bay Colony settlers, Lodge was a remote and prickly man who believed himself to be concerned solely with the good of the nation. And that, of course, included its moneyed interests—but not just them, or so Lodge rationalized. For when he first spoke of supporting the insurgents in Cuba and defended the need for a war against Spain, he insisted that his intention was broadly humanitarian. “We represent the spirit of liberty and the spirt of the new time,” Lodge declared, “and Spain is over against us because she is medieval, cruel, dying.” America was new and vital, Spain old and moribund: Lodge couched his war cry in an appeal to youth—and to the nation’s golden future, even if it would be created by force.