It was May 18, 1926, and the thirty-five-year-old McPherson was known to critics and champions alike as “God’s Best Publicity Agent.” McPherson rose to prominence during the golden age of P.R., when Ivy Lee was talking up the Rockefellers and the Democratic Party and Edward Bernays was selling everything from Dixie cups to the First World War. In keeping with the times, McPherson used mass media to make herself into a master of soul craft and self-promotion, laying hands on thousands of sick parishioners and preaching practically seven days a week to thousands more until her death, in 1944. Her sermons featured elaborate sets and musical numbers, borrowed from the nearby and nascent film industry, including boxing rings in which she knocked out the Devil and a motorcycle that she wheeled across a stage with sirens wailing while calling herself one of the Lord’s patrolmen. “Half your success is due to your magnetic appeal,” Charlie Chaplin once told her, “half due to the props and lights.”

More recognizable than the Pope, McPherson was often besieged by followers, but the ocean offered an escape from their attention, and she liked going to the beach to read Scripture and to write, and then to take a break from both to swim. That May afternoon, she chose a title for her sermon, “Light & Darkness,” and wrote for almost an hour before wading into the water. Jonah was swallowed by a whale on his way to Tarshish, and St. Paul was shipwrecked off the coast of Malta, but no one knows what happened to McPherson after she wrote the following in her notebook: “It had been that way since the beginning. The glint of the sun, gleaming light, on the tops, and shadow, darkness in the troughs. Ah, light and darkness all over the earth, everywhere.”

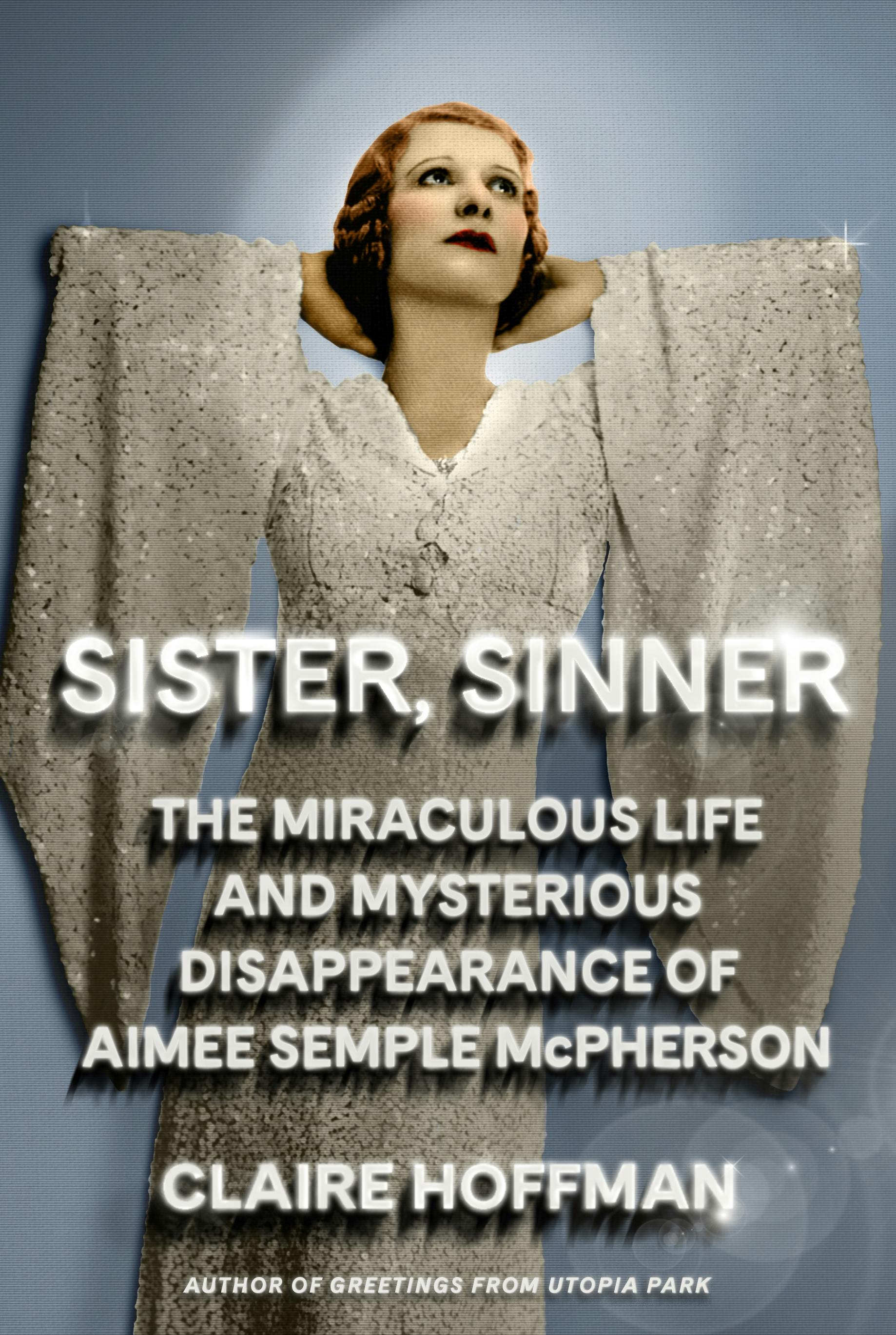

More than a month later, and two days after her own memorial service, the lady preacher reappeared, still barefoot but now wandering around a Mexican desert, hundreds of miles away. McPherson never wavered in her version of what had occurred, but for the rest of her life her friends and family, her followers and detractors, the newspapers and even the courts debated where she went and what she did during the five weeks she was missing. She became—as the journalist Claire Hoffman argues in a new biography—a schismatic figure in religious history: blessed sister to some, conniving sinner to others.