There is little doubt that scribes and woodblock cutters and such absorbed the stab of the movable type printing press, and that stationers felt the stab of modernity when the telegraph came into play threatening sales of paper generally used for letter-writing, an art form that they felt would be diminished by the new technology. At about the same time though came the second revolution in mail delivery, which made it cheaper and more regulated in using a more-competent mailing system, which meant an increase in letter writing. Ditto that for the telephone, which again would threaten written communication. Movies too threatened the theater, and on and on.

And so too for music, the musician, and recorded music. I suspect that in the 53 years since Mr. Edison's invention of the phonograph that not many musicians made very much in the way of royalties for their recorded music, at least not at this early date. (On the other hand my guess is that there was a different economic experience in the sheet music department.) On the other hand, there was a popularization of music far beyond what had been possible in the period before recorded music, so there was at least that direct and enormous benefit.

Then came recorded music in theaters, which was a different thing entirely, as there was no real direct benefit to musicians--in this instance, live accompaniment would disappear in favor of recorded music, and so to the jobs of thousands of players.

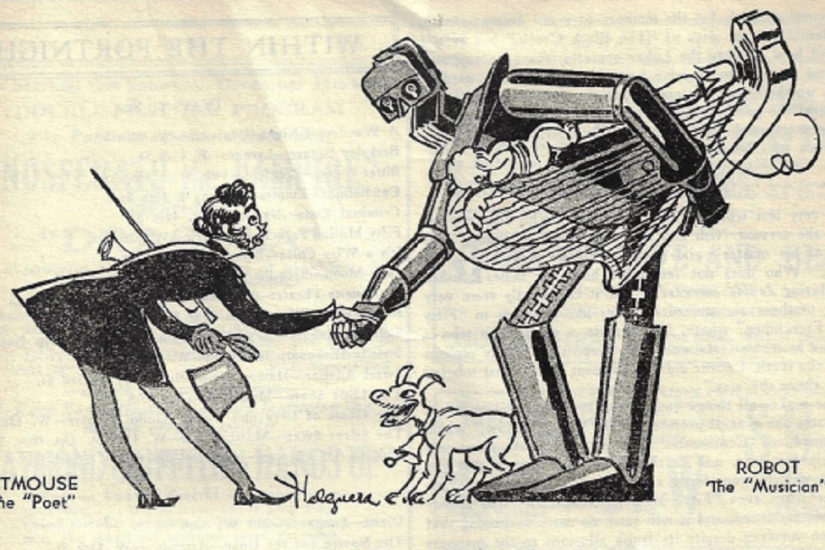

And so the reason for this advertisement in The Nation, placed by the American Federation of Musicians, which found the idea of "canned music" to have nothing to do with "the Art of Music", and representing it as a robot, "a pale shadow of real Music". "Machinery can do many things well, from a utilitarian viewpoint, but music lovers deplore its attempted invasion of music, where only the hands and hearts of gifted humans can give true aesthetic pleasure."

"Surely, America is too intelligent to tolerate--and pay for--a Titmouse conception of the art of music."